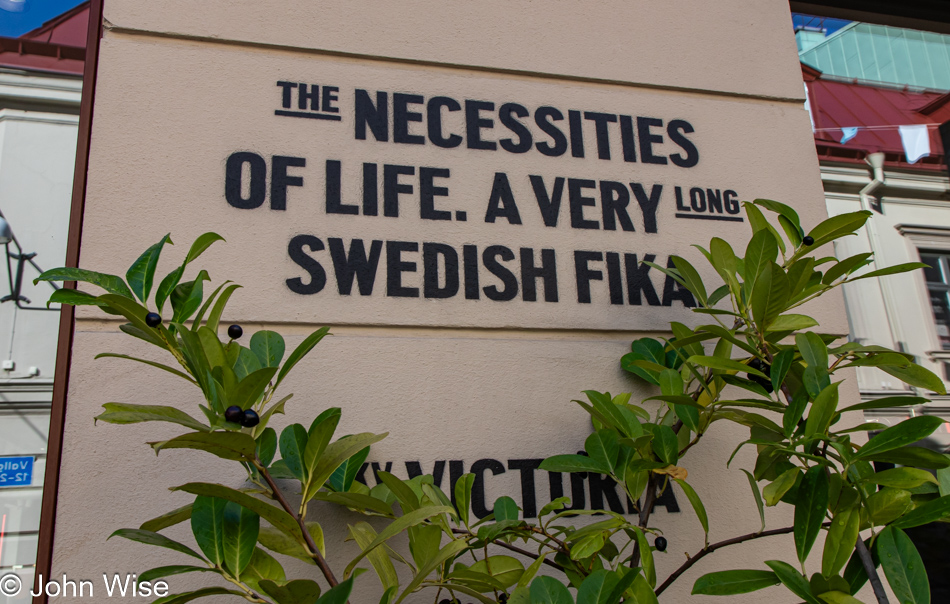

So far, during our stay in Scandinavia, breakfast has been included in the cost of our room, but not today. For the two of us, we were looking at about $55 for the hotel buffet, and while we were assured that everything on it was organic, it was a bitter pill. We headed towards our bus stop, figuring we’d find a bakery, and were proven right. Occupying a couple of stools in the front window, we sat down to share a pretzel croissant, a cream-filled pastry, and a slice of pizza, along with a couple of coffees for only $13 or 140 Norwegian Kroner. Our view offered us the opportunity to watch Oslo going to work and school on foot, scooter, and bicycle. There are a lot of electric cars and e-bikes on these streets, too. Lots of women are wearing dresses, far more than I ever see in the States, while men conform to the international business attire code of blue slacks, light shirts, and tan shoes, and maybe half of everyone carries a backpack. In the 30 minutes we spent grazing and people-watching, a licensed beggar sitting right in front of us with her back to the window did not see a single coin dropped in her cup. I point out that she’s licensed as beggars have to wear lanyards with their badge of authorization, a first for us.

We were just across the street from our bus stop and are still getting used to the fact that pedestrians have the right of way and just keep moving when entering a striped crosswalk; cars will yield. If the intersection is controlled by walk/don’t walk signs, the public waits, although even those signs feel like mere suggestions. Once on the bus, signs asking for civility are strewn about, such as this one asking people to keep their feet off of the seats. Also, notice that USB connections are offered and that nothing is written or carved into the panels. Hey, America, are we animals?

We’ve arrived out on the Bygdøy Peninsula and are early, which is perfectly økey døkey with us as we have some time to take in a different view of the Oslofjord on a perfect day. Who wouldn’t want to do exactly that?

Olav Bjaaland, Oscar Wisting, Roald Amundsen, Sverre Hassel, and Helmer Hanssen are memorialized here at the Fram Museum for their courage in being the first five men to reach the South Pole.

There are five museums out here in Bygdøy, but one of the must-sees is currently closed until approximately 2026, which is unfortunate as they have the best-preserved and largest known Viking ship excavated from a burial site, the Oseberg Ship.

It was bound to happen at least once on this trip to the watery lands of the north, and with time to spare this morning, it seemed like a great time to kick off the shoes and step into Oslofjord. I have to wonder if anyone else’s feet in the history of humanity have bathed in so many diverse locations from around our earth as Caroline, who has stepped into the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, the North, Baltic, and Mediterranean seas, the Gulf of Mexico, and countless lakes and rivers including the majority of America’s biggest rivers.

I found a mention of this being the Bygdøynes Light or maybe Lantern, with no other supporting information than a guess that it’s managed by the Norwegian Maritime Museum. Just after taking this photo, we dipped into that museum and snapped off a couple of images but were more excited to get into the Fram Museum next door.

More wow on this trip, this time in the form of the wooden ship that delivered a crew to the Antarctic, allowing Olav Bjaaland, Oscar Wisting, Roald Amundsen, Sverre Hassel, and Helmer Hanssen to be the first five people to ever visit the South Pole. If you don’t know the story, here’s a quick synopsis: Roald Amundsen and his crew set sail in the summer of 1910 on the polar ship Fram for the Arctic, but when they reached Madeira, Portugal, the captain told his crew that they were, in fact, going to the Antarctic. They landed in January 1911 and, by mid-December of the same year, had reached the South Pole. A month before Robert F. Scott arrived, too late.

The ship is packed with original gear and artifacts from the time of the expedition, except for this creepy guy, who I believe is a prop and not a mummified original crew member.

Not only were we able to visit the deck, quarters, and galley, but also climbed nearly to the bottom of the hull. We peered into the engine room and were able to check out the storage areas with furs and other equipment that helped sustain the Norwegian explorers.

With a windmill up on deck to generate electricity, the Fram was equipped with electric lights, which must have been a luxury.

In 1935, it took more than two months to pull the ship onto dry land and its final resting place where the structure housing it was built. It was only in 2018 that further restoration work opened the crew quarters and other areas below deck to the visiting public. Right there in the center of the photo is the windmill that supplied the crew with electricity.

The lighting of Fram left a lot to be desired, and while I’m sure my phone would have better captured the available light, the quality of those images is just too poor. A tripod would have helped, but rarely, if ever, are those things allowed into and onto historic exhibits, so my images are a bit on the dark side. As intrigued as we were seeing the Vasa over in Stockholm, this ship, too required us to capture what we could to memorialize the day we stood on her decks and were able to explore such a historic part of the age of polar exploration.

It’s crazy to think that just about 110 years ago, the first people explored the South Pole via a wooden boat without a two-way radio, and today, we deploy solar-array powered space telescopes orbiting the sun a million miles from Earth. The engine on the Fram had about 700 horsepower, while the Ariane 5 rocket that launched the James Webb Space Telescope had the equivalent of more than 3 million horsepower. While Amundson’s crew was capturing black & white images in the equivalent of 8 to 10 megapixels compared to today, the James Webb telescope is sending us images that, after processing, can be as large as 123 megapixels. The tragedy that is apparent when I consider the progress we’ve made collectively is that the ship of humanity is listing while our tools have eclipsed the ability of our individual minds to rise to the occasion and propel our species into the future.

Fram, Norwegian for forward. It should be the motto of humanity instead of Frykt, Norwegian for fear. If you ask me, fear should be pronounced “Fukt.”

This is the third museum we visited this morning; it plays host to the efforts of Thor Heyerdahl. The Kon-Tiki raft, made of balsa wood and other native materials, proved Heyerdahl’s theory that early explorers could have traversed the Pacific Ocean on such a raft just as he and five others did back in 1947. Regarding the specifics of his other controversial claims, I don’t rightly care as I was more fascinated by the details of their precarious journey that carried them on a 101-day, 4,300-nautical-mile (5,000-mile or 8,000 km) adventure over the vast ocean.

This is the other craft in the Kon-Tiki Museum, the Ra II papyrus boat, which carried Heyerdahl and six others across the Atlantic Ocean.

Done with yet another museum and onto the next, the Norwegian Folk Museum.

Similar to the Museum of Cultural History in Lund, Sweden we visited less than a week ago, the folk museum looks at elements scattered across the history of Norway. Drawing from buildings and artifacts that could be moved out here to Bygdøy, these things were collected, rebuilt, and put on display in order to preserve parts of Norwegian history that would otherwise disappear.

There are 160 buildings representing Norway from the past 500 years on display here, with many of them open for a visit. The ones that are locked up are likely open for visitation during the main tourist season. This also then has us asking if there are more people on hand in period clothes to help the buildings come to life…

…such as this old grocery store from Oslo announcing milk and delicatessen goods sold by this young lady at the counter.

This was as far as we could go in the pharmacy, as it was like many of the exhibits, protected by a plexiglass barrier.

A guided tour would have been great here as, aside from impressions, there’s not a lot to be learned, with signage being at a minimum.

Being present in these environments, even without a narrative, works for Caroline and me as once we’re home, we have the ability to discover more about the history of the people, art, architecture, culture, and politics with the experience of having been immersed in places where we gained some small amount of the sense of things and are now ready to contextualize what we are learning.

The buildings here at the Norwegian Folk Museum are not recreations; they are authentic, and so I understand why they can’t really be put to work, but all the same, I can easily imagine a space where we could sit down for a meal set to some point a few hundred years ago. This is something that Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia does exceptionally well.

I would be remiss if I forgot to share that Caroline had recommended that we pick up a couple of Oslo City Passes that paid for our transportation and museum entries for 24 hours; it turned out to be a great deal. If someone is visiting Oslo for a few days, the 72-hour city pass is an incredible bargain at only $80 for 35 museums, busses, trains, and even the public ferry.

This old farmhouse was once the home of the Lende family from Jæren, Sweden.

Sadly, the City Pass didn’t convince the driver of the horsecart to let us get on board.

Wow, an original stave church from the 1200s. This one was moved to Bygdøy from Gol, a couple of hundred kilometers north of Oslo, back in 1884.

Somewhere in here is a stave with a rune that reads, “Kiss me because I struggle.”

These churches were Christian, though some of the imagery and forms evoke something pagan for me. As for the term stave church, the name is derived from the fact that the support structures are vertical posts and planks, known as staves. Considering that these medieval buildings were made exclusively of wood, we are lucky that even one of them survived the intervening 800 to 900 years.

I suppose this could negate my previous statement about being built exclusively of wood, but I hope you get what I meant, as it was not implied there were no iron flourishes here and there.

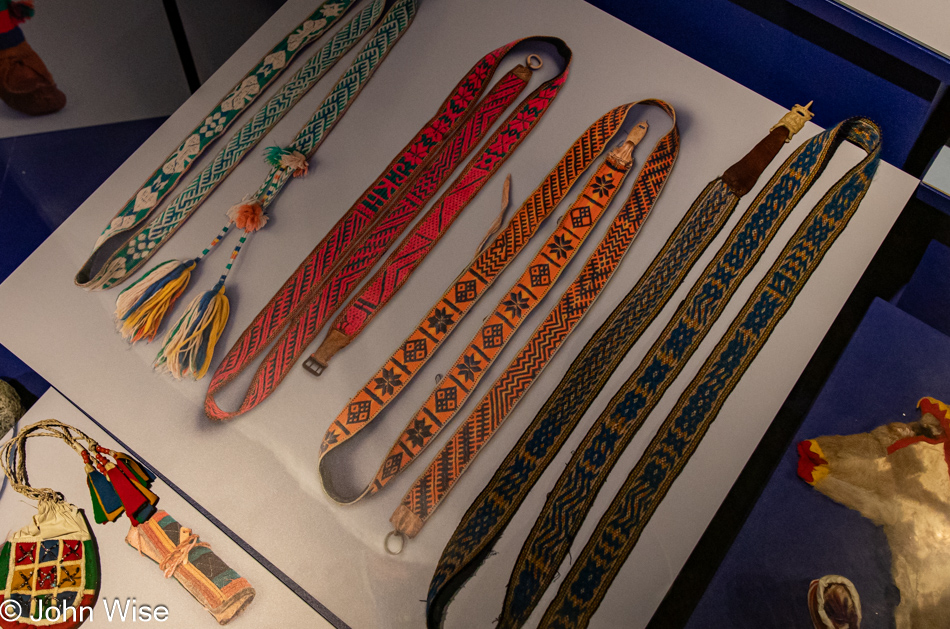

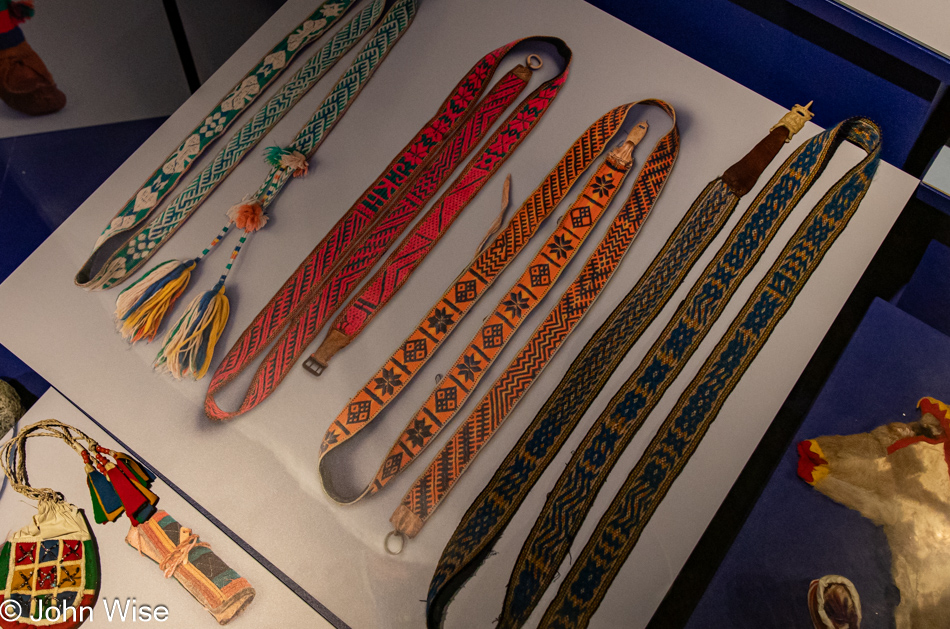

Ladies, gentlemen, and non-binary people, I now return you to that part of the story where the fiber arts are center stage again. These four straps are examples of backstrap weaving.

When one begins to understand the efforts made by our ancestors to create culturally unique clothing for pageantry, marriage, special occasions, or just to look one’s best, these clothes begin to take on extra significance, especially in contrast to the mass-market clothing that from certain perspectives reveal that it is only the rare individual who actually wears anything unique in our modern age.

I’ve often heard the argument that without a job, people would have no purpose; I’ve even heard this from women who deride the idea of being “just” a housewife or mother. First of all, mothering is the single most important thing half of humanity is capable of doing at some point in their lives. If Caroline had more free time, we’d have a coverlet handwoven by her, but to weave the length required and then sew them together is a Herculean effort, and that’s even before considering creating embellishments such as borders or fringes. The same applies to our clothes, hats, straps, pouches, bags, and other things that would benefit from flourishes of handcrafted beauty. Having free time, extraordinary amounts at times, allows us to discover and create greater meaning regarding many facets of our lives that we’d never discover otherwise, such as this incredible opportunity I indulge in by writing about the experiences shared by Caroline and me.

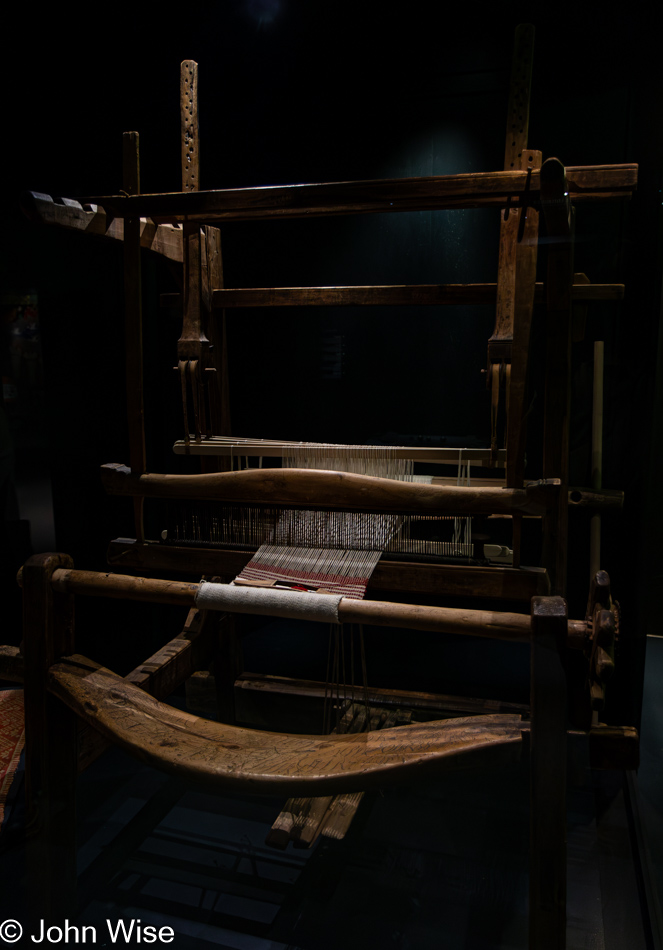

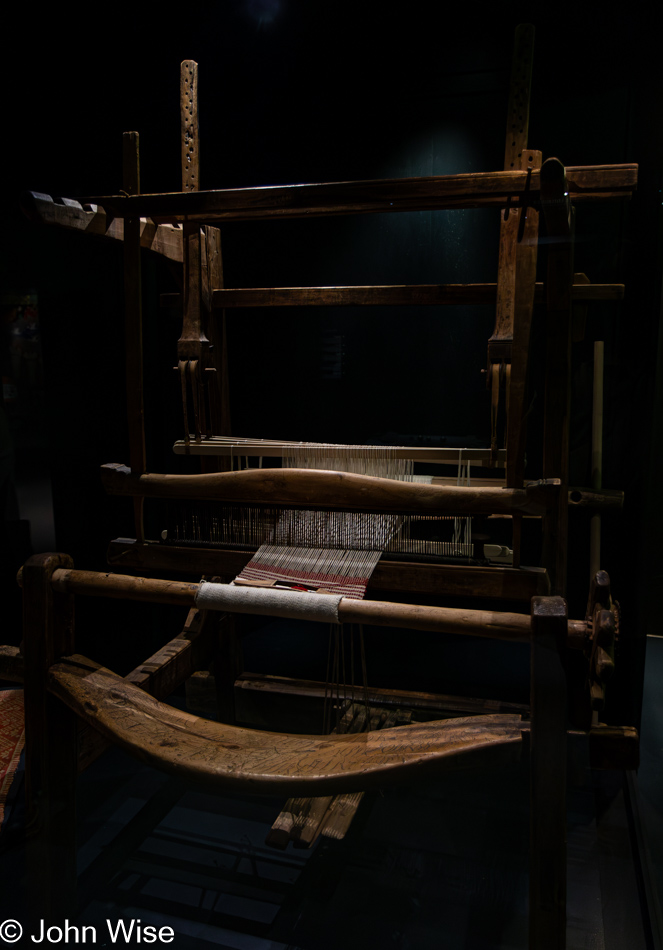

The Stradivarius violin has a reputation for being a work of art, but what of things like this well-worn loom with perfect lines and a hidden history of the cloth that was made thread by thread and possibly worn by someone of significance that impacted all of our lives?

Who among us would have the skills to make a hand-carved wooden wine jug that wouldn’t leak? I’m guessing this vessel had something to do with drink and merriment as the two guys at the table have glasses in their hands while one is empty, awaiting the jug of drink. My first thought was how something like this was sealed from dripping away its contents, and good ‘ol artificial intelligence guru Claude offered me multiple ideas of how to accomplish such a thing, but I’m opting for a combo. Claude shared info about using precision-carved wood staves. The vessel sure does seem to feature those that would be bound by willow or metal bands, and while I don’t know if they are willow, they are certainly bounding bands that wrap the pitcher. I also learned about various substances that could be used to line the interior, and in my mind, I’ve settled on wax as being the most neutral for serving alcohol.

After our Norwegian Folk Museum experience, we were ready for more Norwegian nourishment and ate in the museum’s cafeteria before heading back to the city center.

The availability of yarn in a city must be a measure of civility. For the second time in two days, here’s Caroline with yet more of the fluffy stuff, this time from Fru Kvist Yarn. By this fact alone, Oslo has become more and more sophisticated from our viewpoint, but then take into account that the skeins Caroline is holding are yak wool from Mongolia and undyed Norwegian yarn, and I think my wife is ready to call Oslo home.

It’s seven weeks since we stood here at the foot of Oslofjord and about five and a half weeks since we came home that I’m writing this post, and I’m yet to miss a day of doing such. As a matter of fact, writing actually intensified after our return because there was no sightseeing from within a Phoenix coffee shop while I tried to tease a cohesive narrative out of my notebooks and photos to create a lasting story that would remind Caroline and me of the many beautiful things and places we enjoyed during our time in Europe and specifically Scandinavia. I work relentlessly on this process since I’m afraid if I take a day off, I’ll lose momentum or forget to finish the trip (it’s happened before). And so, I turn to the coffee shop literally every morning without fail in order to channel my attention to hopefully discovering some tiny amount of finesse in describing experiences that have more or less been had by many millions by this time. Consider, though, that maintaining a bead on all things vacation leads to some serious tunnel vision and that there are times I wish to be someplace, any place else but here at the keyboard, exploring my mind for the possibility that I can discover an insight meaningful not just to us but others who might stumble on these posts.

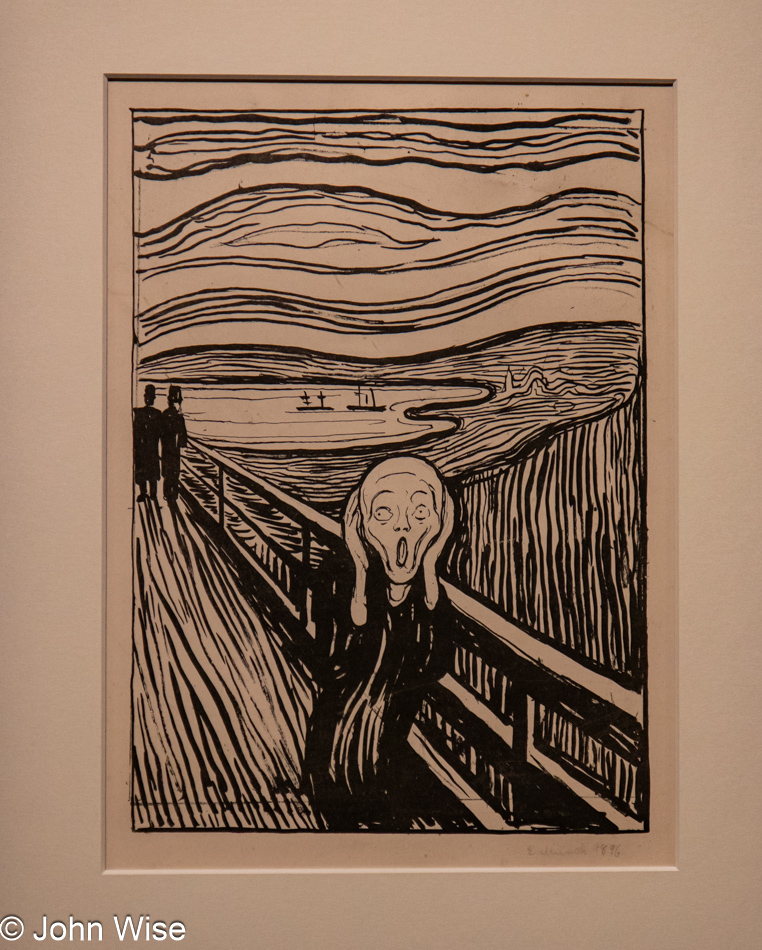

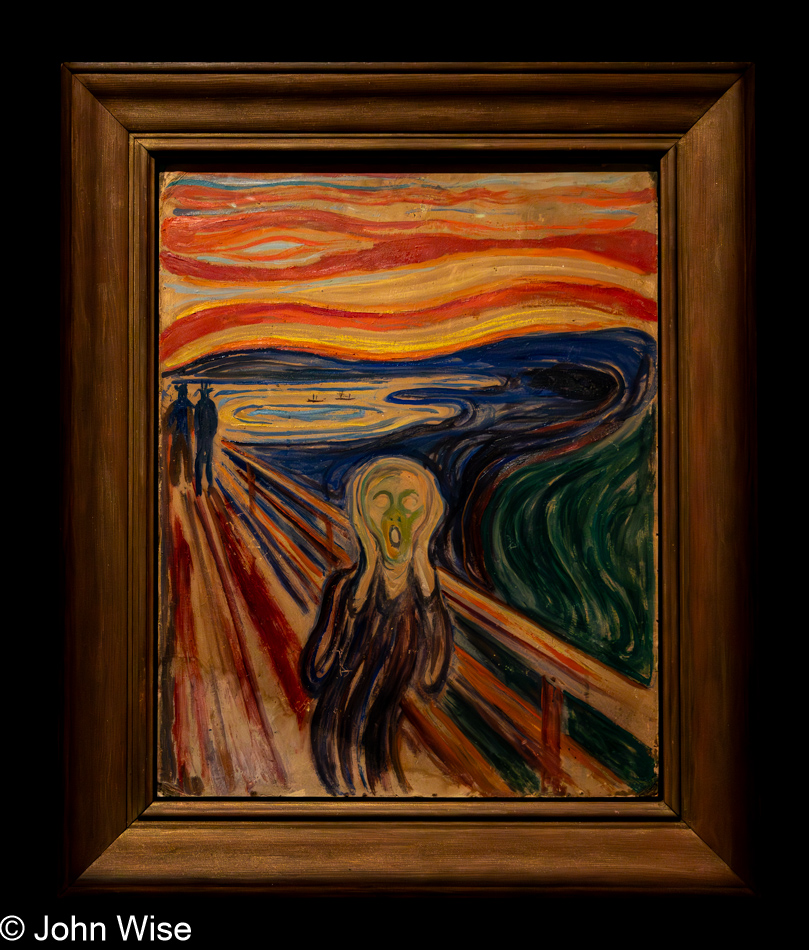

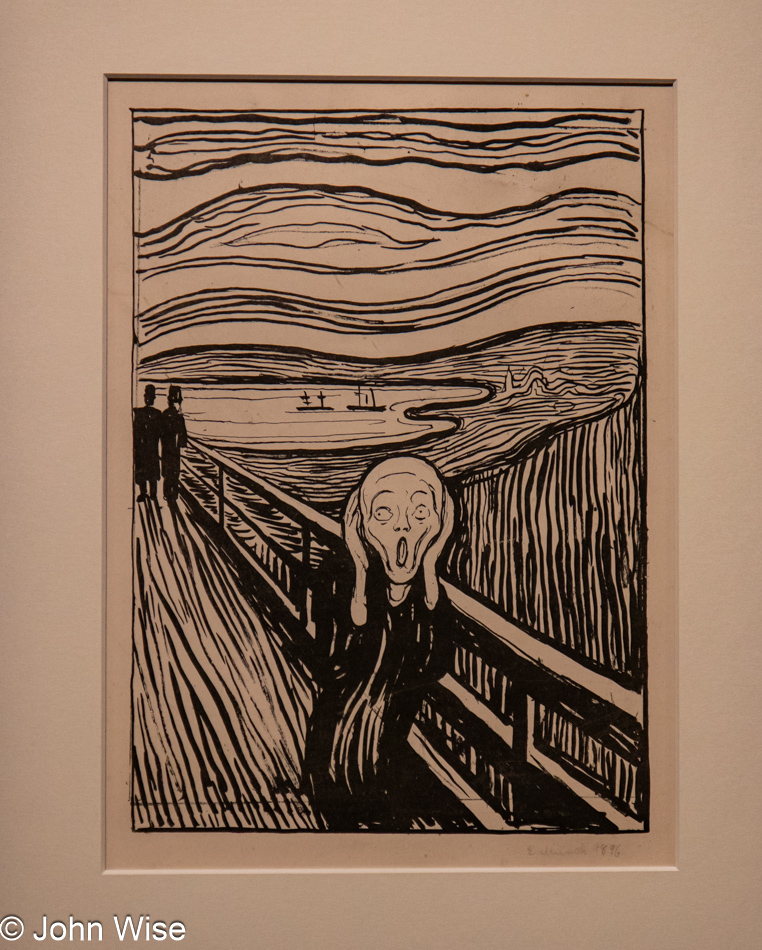

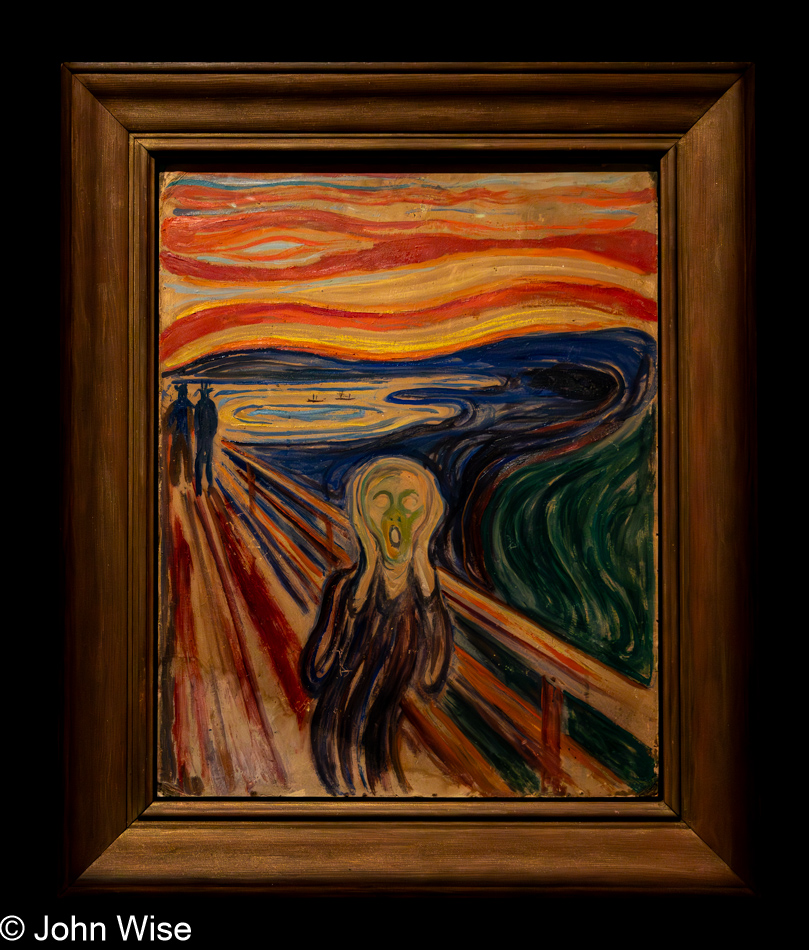

The title of these posts from Oslo, Norway, would better be served with “Wrong Impressions of Oslo Cured By Destroying Misperceptions.” I can readily admit that I wasn’t exactly drawn into making a pilgrimage to a museum that could only be focused on the single piece of art that Edvard Munch is internationally known for. Everyone wants to see The Scream, and I honestly believed it was the only thing of his that was known. Of course, I was wrong, just as I’ve been about almost everything here in Oslo.

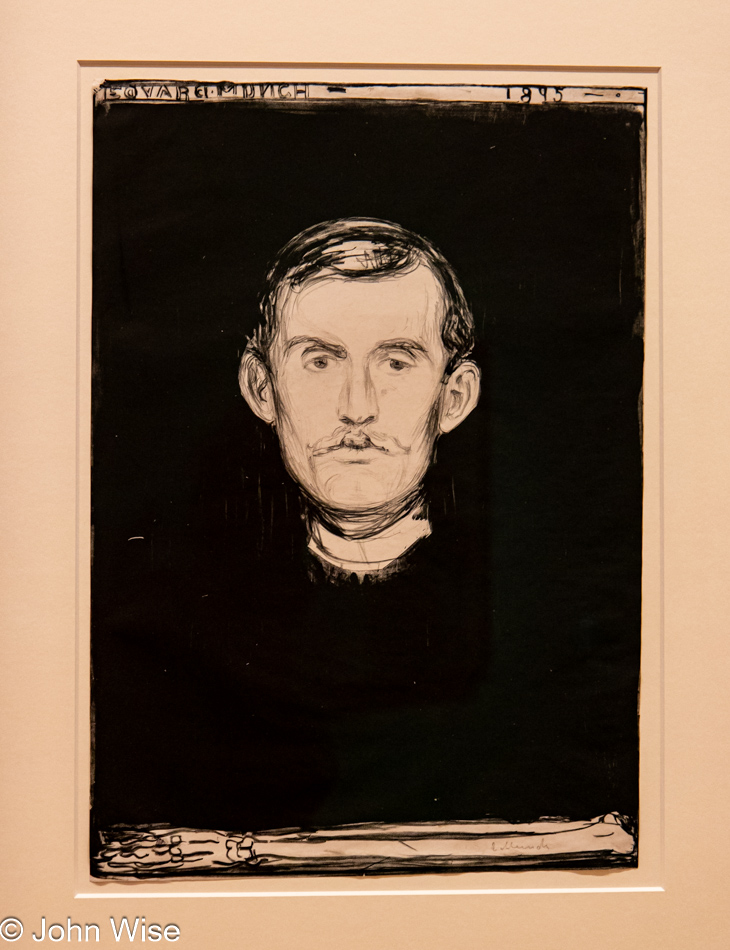

Some forty or so years ago, when I first learned of this piece titled The Scream, I was enchanted by its sense of the apocalyptic, but in the intervening years, I grew bored of it as overblown media saturation, and its place in the meme foodchain removed its gravity. Seeing it in person is okay and satisfies the collection of cultural treasures experienced firsthand, but it’s smaller than I thought. Then we learn that each of the three versions on display is on a cycle that helps protect them from exposure to light, so if we want to see the most famous of them, it’ll be about an hour before it cycles back. We were fully prepared to have only seen this black-and-white version because what else did Munch do? To those of you who might not know, Munch is pronounced: “Moonk.”

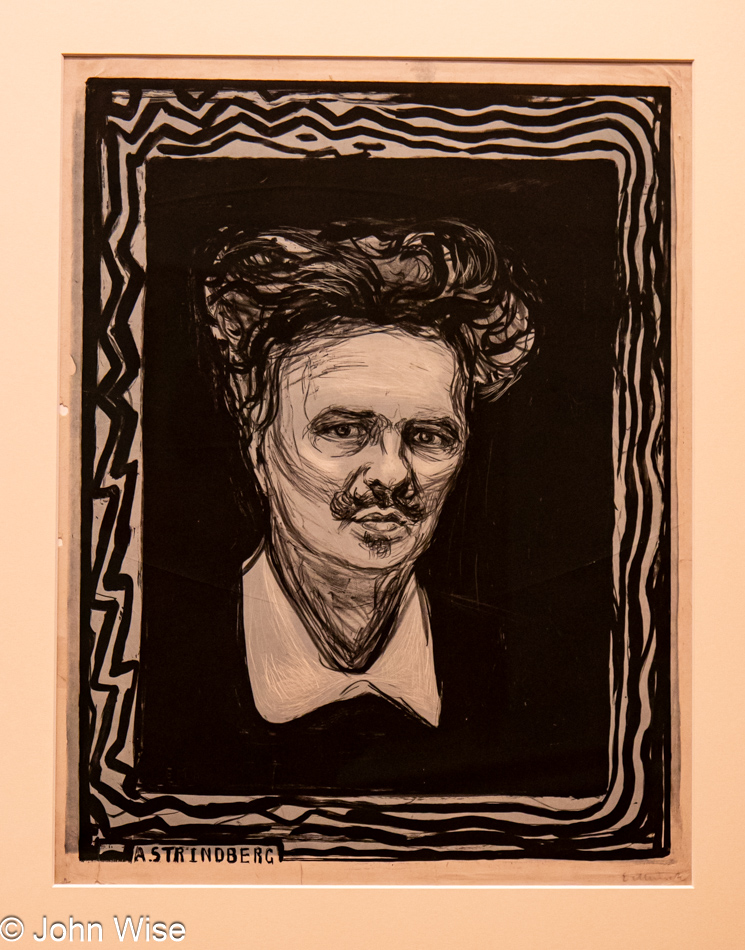

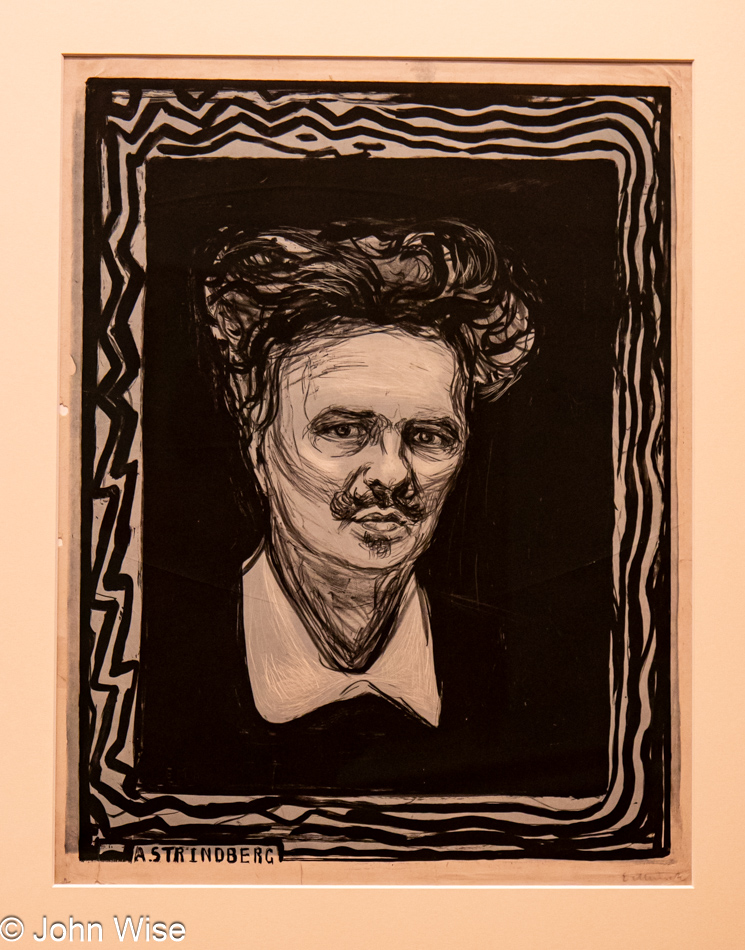

NO WAY!!! I’ve known this portrait of August Strindberg since I bought my Penguin Classics copy of Inferno/From an Occult Diary, but I didn’t realize that it was painted by Edvard Munch.

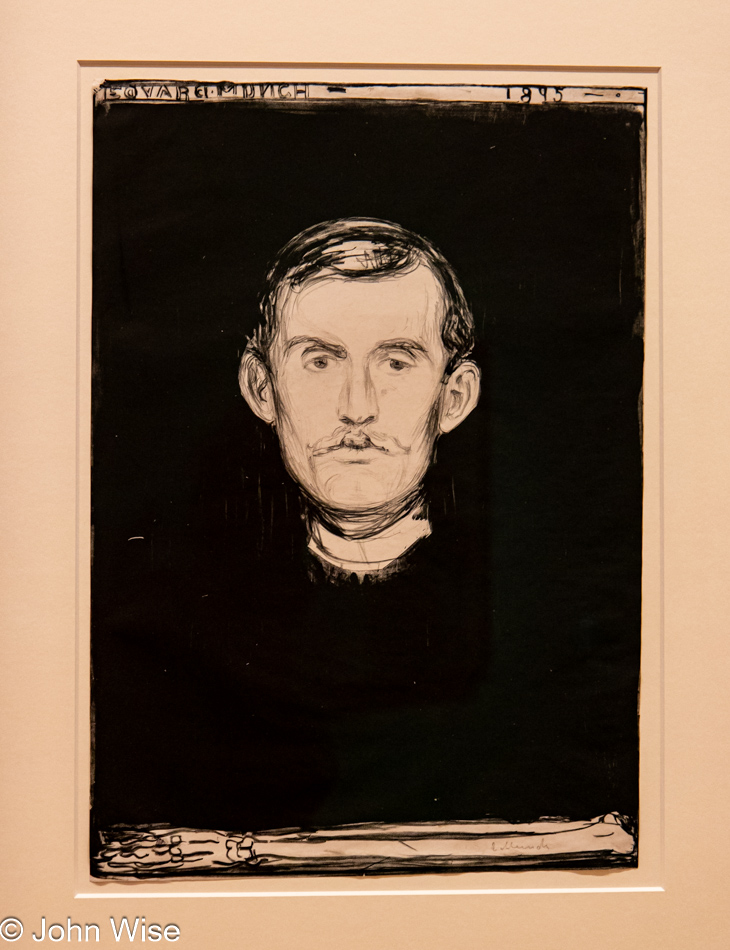

I’ve also been aware of this portrait of the artist himself, but never once have I really considered the provenance. Not far from these portraits hangs a colorful portrait of German philosopher Friederich Nietzsche, which bears some slight resemblance to The Scream, except Nietzsche is on the other side of the bridge, and he’s not in the pose of a scream. I think that it’s a subtle nod that Nietzsche’s screams are from within and that he’s on the side of reality where losing one’s mind can still be salvaged.

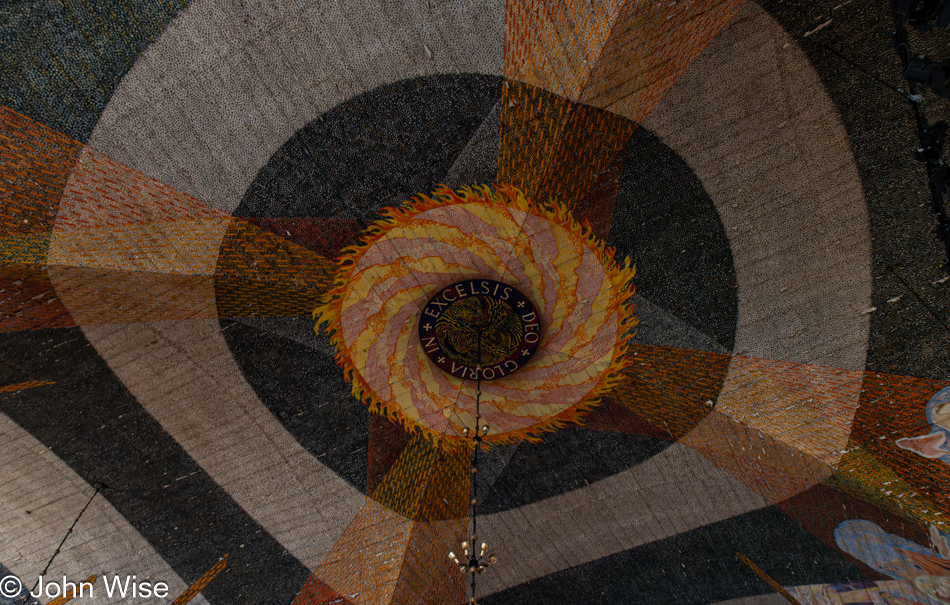

In yesterday’s post, while writing about the Oslo Cathedral, I was pondering who influenced whom, while Caroline pointed out that the ceiling of the church was painted by Hugo Lous Mohr. Well, it was this painting here by Munch that raised the question.

I honestly didn’t think we’d be around to see this version of The Scream, but here we are and have now seen all three.

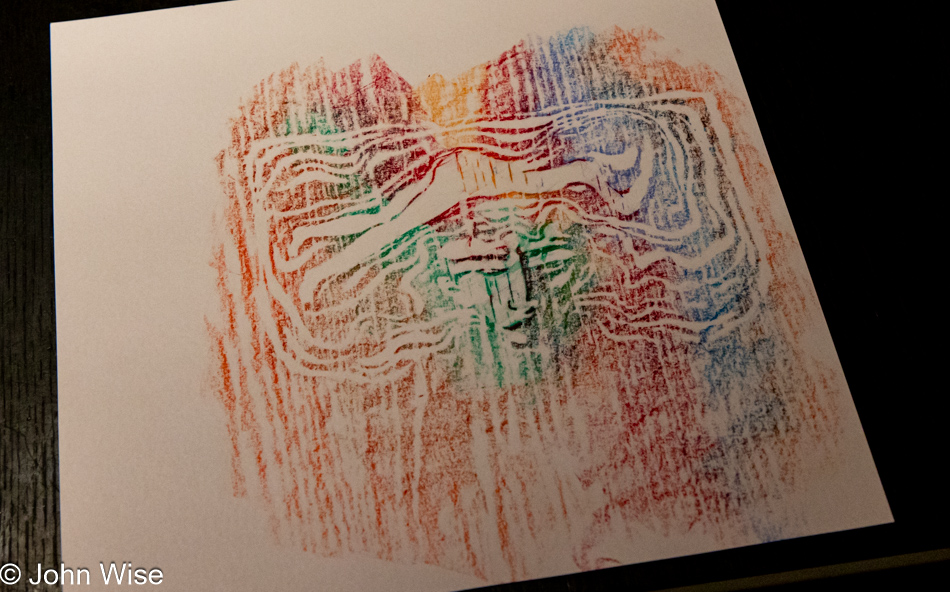

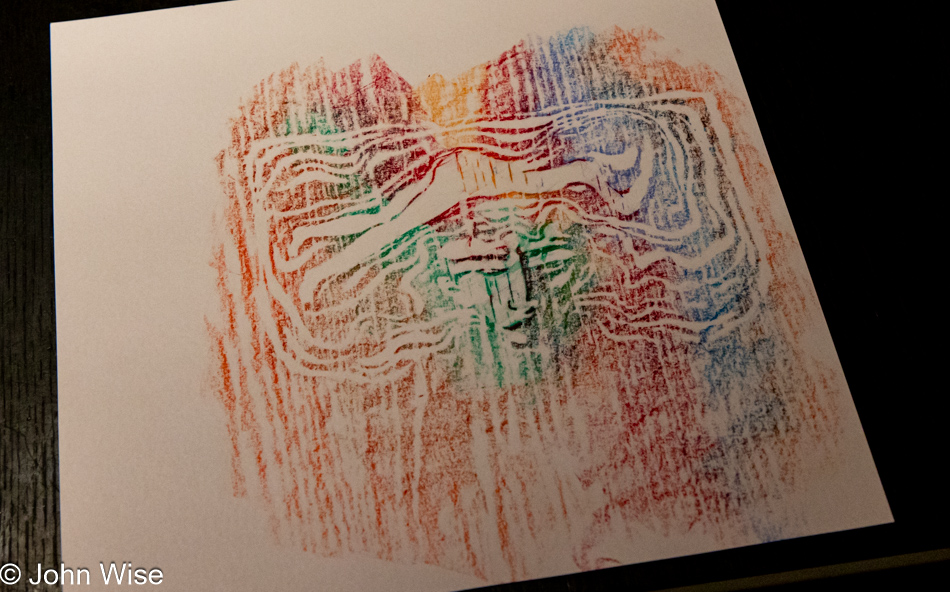

On one of the floors of this large museum is an area where there are a number of carvings (based on a number of Munch pieces) embedded in a table. An ample supply of paper and wax pigments allows aspiring artists and others wanting to have fun to grab a seat and start rubbing images into the paper as a souvenir of their time at the Munch Museum. This was Caroline’s attempt at the art of frottage.

Self-portrait with seldom-seen hair out of ponytail.

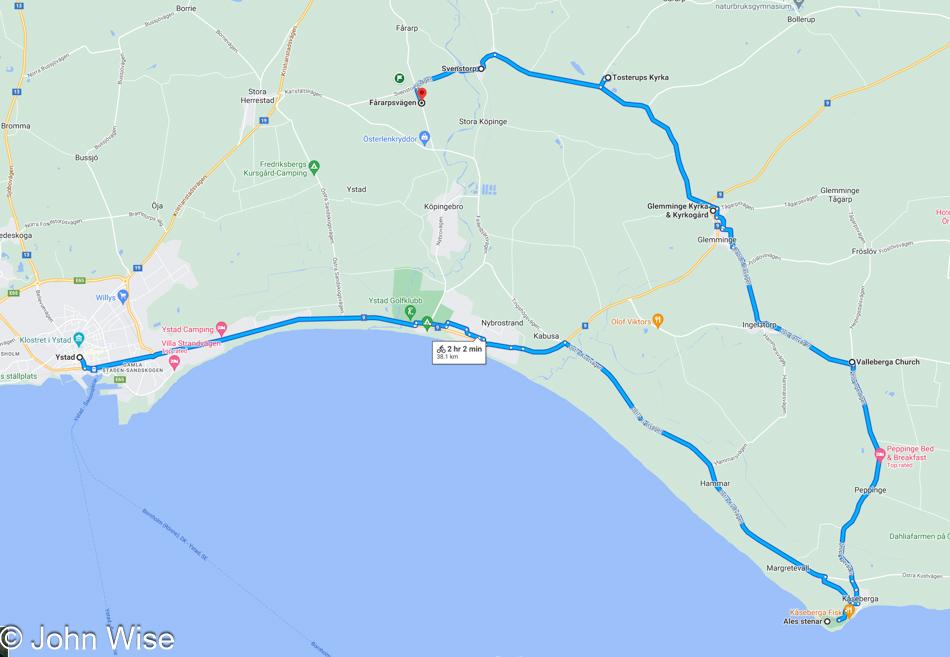

This huge sculpture is called The Mother and was created by U.K. artist Tracey Emin, who was inspired by Munch to become an artist. This is a relatively new addition to Oslo prompted by local Norwegians who petitioned the city to build the location with access to swimming in the fjord during the earliest days of the COVID-19 epidemic. The reclaimed land was christened Inger Munch’s Pier after the youngest sister of Edvard Munch. I almost forgot to point out that even the Munch Museum is new and only opened in October 2021.

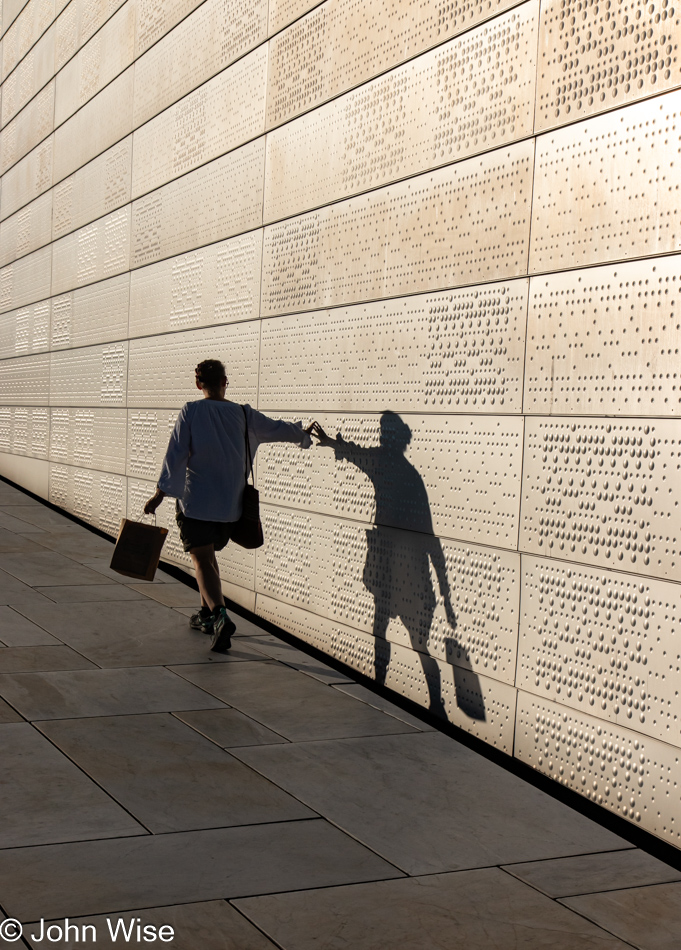

The idea of creating a giant public plaza sloping up from sea level to a viewpoint allowing visitors to look over the city, was a brilliant one. Caroline and I are on our way up.

By making the architecture of the opera accessible to Osloers and tourists alike, the building becomes incredibly familiar and personal, removing some of the sense of exclusivity that often is a part of the opera which is typically only visited by paying guests on performance days.

Now, the opera is available to everyone who wishes to create a kind of mini-performance piece where they are the actors with the city creating the soundtrack.

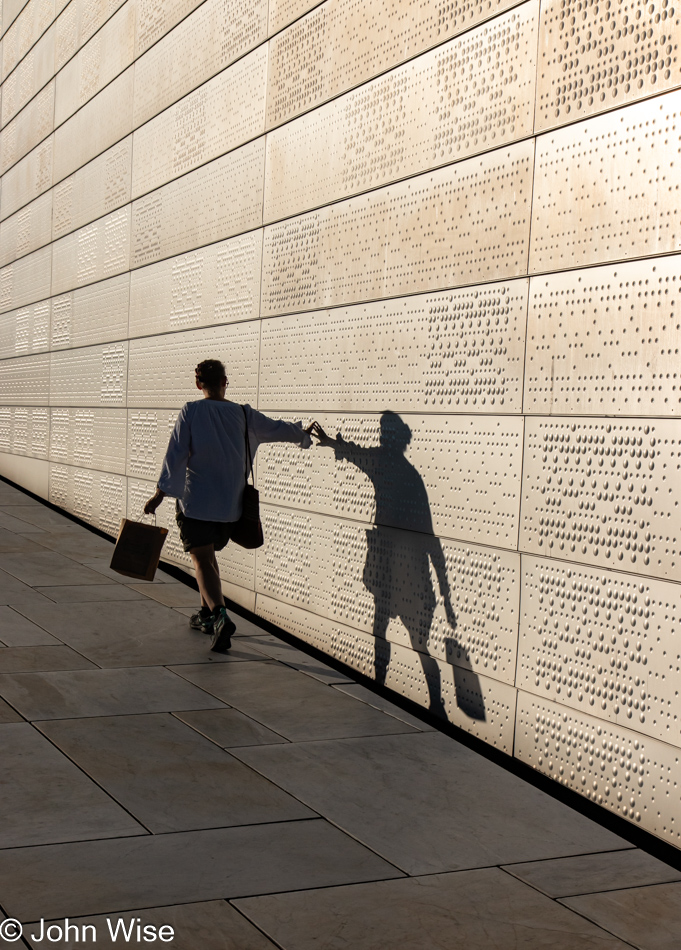

The white aluminum-clad exterior of the stage tower is meant to evoke old weaving patterns, which is likely part of the reason Caroline was compelled to reach out and touch it.

Time to put a mark on future travel plans to return to Oslo and gather a few other views from this remarkable building, but will we ever be so fortunate again to be treated to two consecutive beautiful days of perfect weather?

I could have hung out here from sunrise to sunset just to study the light and the flow of people as they become part of a story developing on the shore of Oslofjord. I now have so many questions about the construction of this plaza and a curiosity about what other buildings the architects might have contributed to.

Vår Frelsers Gravlund (Cemetery of Our Saviour) is where you’ll find the gravesite of the man who will Scream no more, Edvard Munch. In another corner of the cemetery, you may visit the grave of Henrik Ibsen who’s not penned a play in more than 117 years.

From the cemetery, our path took us through the Gamle Aker District.

For a brief moment, we thought we were entering a sketchy area where someone loves sluts, but just as quickly, we were back in the safe arms of a city with but a few smudges, as far as we could tell.

Not wanting to take anything for granted, how it worked out that we passed a dozen other places to eat before settling on the Oslo Street Food was a stroke of good luck that feels inexplicable that everything else didn’t strike a chord. This former home to Oslo’s largest indoor pool, called Torggata Bad, now hosts a multicultural selection of foods uncommon to the Norwegian palate. While the food court stops serving at 10:00 p.m. on weeknights, this place becomes a nightclub on weekends, open until 3:00, with the former pool area serving as the dance floor. It was on that pool floor where Caroline and I shared a tonkatsu don from Gohan and empanadas from De Mi Tierra.

After a short walk following dinner, we opted for a tram ride to the hotel as the extra mile felt impossible. The sauna had the same difficulty enticing us to step in as tired was overtaking us. Tomorrow, we will embark on another six-hour train ride, considered one of the most scenic on earth.