Rapids and more rapids, we haven’t seen so much whitewater since leaving the 20’s back on day two. From our overnight stop at Granite Camp, we were in position to begin the day with a wild ride. This is a roaring monster of spit and foam, not a read-and-run rapid; it is a “get over there and inspect before plunging in” rapid. We tag along on a short hike to an overview to watch the inspectors do their job. Standing on an outcropping above the riverside, trying to gauge the size of the rapids remains mostly elusive to my ability to give more weight or thrill factor to one wave compared to another – from up here, they don’t look all that large. This problem exists due to the scale of this massive canyon, similar to when one walks the Strip in Las Vegas, and the block-long hotel-casinos dwarf one’s idea of normal building sizes, giving the illusion that distances are smaller than they really are. It isn’t until you are halfway between the Luxor and the Bellagio, with a long walk still ahead, that you begin to appreciate the scale. And so it is here. Looking out at the raging water from shore, things look easy and manageable until another boat races into the picture, giving perspective to the relative size that immediately instills respect for the skill of the boatmen who will guide our minuscule crafts through that angry gnarl of crushing danger.

Just as quickly as these men from another group appear on the river in their aluminum powerboats, known as Osprey, the first one disappears behind a wave until his hull jets upward, climbing out of chaos to bolt forward. The next pilot floats down the tongue of Granite Rapid in reverse, and when it is nearly a second too late, he guns the motor and whips the boat in a 180-degree turn to plow face-first through what could have been a ruinous wave. Zoom, and he’s moving hard, and so is my adrenaline, watching his expertise and familiarity in taming this wicked hydrological performance put on by the Colorado, all the while looking as cool as a cucumber.

Motorized craft are a rarity on the river this time of year. From mid-September through the end of March, the river is governed by the No-Motor Season. The giant rafts that push a dozen or more passengers each downriver during the summer months are cut off. This rule arose out of a compromise between those who want to travel the length of the Canyon in its quiet, pristine state and the interests of commercial operators. These tour companies ferry large groups during the busier summer season, catering to tourists who may have limited schedules to enjoy a journey down the Colorado. Our group, which departed on October 22nd, like all commercial and private river trips this time of year, glide along in silence with nothing more than oars and human power allowed to add speed to the journey. These guys on the Ospreys are an exception. We first saw them yesterday, hidden nearly out of view. They are research biologists working in coordination with the National Park Service.

These field workers are here in an attempt to save the humpback chub, a native fish adapted to surviving the muddy, once-warm waters of the Colorado. Nowadays, they are on the endangered species list because their habitat has been radically altered, and their chances for survival are slim. The Glen Canyon Dam releases water from the depths of Lake Powell at a near-constant 46 degrees. The chub north of the dam and in the lake no longer have a warm rushing river to support the species’ habitat and are also at risk from the predatory fish introduced into Lake Powell. Chub formerly ranged from below Hoover Dam up into Colorado; today, they are found in just six areas, small stretches of the Colorado itself and a few of its tributaries. Trout, walleye, and bass, all of which are better suited to cold, clear waters, are known to be decimating the chub population in the lakes and the remaining wild river habitats.

As humankind discovers the damage we have inflicted on the environment, displacing flora and fauna and introducing invasive species, tragically allowing our convenience to take precedence, people are waking to the need to ensure biodiversity in order to maintain the balance of nature and our own survival in these fragile ecosystems. In our efforts to correct or at least mitigate the continuing damage, there is a growing body of scientists and individuals hard at work to repair, restore, and protect these corners of our planet. Here in the Grand Canyon, the National Park Service is cooperating with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Arizona Game & Fish, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Grand Canyon Wildlands Council to continue the difficult repair work. Unfortunately, it will likely take generations to combat the hostility that has been fomented by groups who do not see the need for natural environments to remain in the state nature created them. Luckily for us, these same forces haven’t found anything of interest to harvest from humans besides our labor.

Most of the effort to save the humpback chub focuses on two areas: the Little Colorado River behind us and Shinumo Creek, 46 miles downstream. Biologists, boatmen, and their cooks form self-contained units that work for periods of 14 and upwards of 30 days on the river – their job is to eradicate trout and translocate chub to test areas in an attempt to establish thriving populations of this native fish. The researchers monitor the populations and their movement patterns to better understand the species and aid in their survival until the day their habitat is restored.

Now, it is our group’s turn to run Granite. This rapid is rated class 7 to 8 and will drop us 18 feet in seconds. This is one of the rare opportunities where we’ll run a rapid in two groupings. I’ll be in the second group, allowing me to watch two of the other dories and two of the rafts tumble over the whitewater. The first to run is the Shoshone, piloted by Rondo. His dory nearly disappears behind waves that hide boats and passengers. As the craft escapes the clutch of the river to glide above the tumult, the sight of its reemergence is breathtaking. The next dory follows suit, and it, too, is accelerating as its perfect form finds a track, delivering a command performance. Standing on the river’s edge, I am fully able to appreciate each tilt, roll, and turn. I can watch with attentive eyes as the boatman places an oar left or right, making corrections. When the dory climbs a wave, the angle of ascent is shockingly obvious, its descent precarious. It could be debated which is more exciting, watching others careen over the fury or riding the explosive waters yourself. While watching from the shore, you experience the rapid vicariously and in perfect safety, knowing what your fellow passengers are going through. After the rafts make their run, it will be my turn. Helmet on, tighten my life jacket, and hold on.

Back in the dory, my breathing is shallow. The strangle grip I have on the strap and gunwale is meant to assure me. My brain is struggling to comprehend the complexity of chaos we are surrounded by. Over the thunder of the crashing water, ears strain to hear commands that, once conveyed, may be the words that stand between safety and danger. Waves slap over the bow and slam us from overhead. Cold water breaks through my frozen, clutching hands, reminding me that I am still able to move. Then, as I remember to breathe, it’s over. And with a pitch unfamiliar to my ears and piercing to others’ senses, squeals emerge out of me with uncharacteristic high frequencies, announcing the joy and relief that we have been safely delivered to the other side.

Hardly another mile is traveled before notoriety jumps back into our faces – Hermit Rapid, the one and only God’s own roller-coaster. Some of these rapids stand out due to the stories written of their dangers. Thanks to the advent of streaming video on the internet, a search for “rafting Grand Canyon” introduces us to rapids and harrowing boat flips while sitting in front of our computer. Once witnessed at home, they grow into legends in our imaginations. Now, out here on the river and confronted with these familiar names, my eyes bug out in recognition and the memory of what I have already imagined a particular rapid to be. Hermit Rapid autographs my book of the conquered with a safe run. Boucher Rapid is up next, aced.

Crystal, oh my, it’s the Arnold Schwarzenegger of rapids – I can hear it tempting me with the question, “Are you ready for this, or are you a girly man?” Crystal is one of those places to get off the river and inspect which level of crazy the rapid is spewing today. Crystal was hardly a rapid at all until, in 1966, Crystal Canyon delivered a boulder storm that choked this channel of the Colorado. Then, in 1983, due to record runoffs from snowpacks up north and Lake Powell close to topping Glen Canyon Dam, its operators were forced to release an unprecedented flood of water. The nearly overwhelmed dam filled the river channel with flows approaching 100,000 CFS. As a result, Crystal became one of the most dangerous – and infamous – rapids on the river that summer, claiming more than a few lives. Today, it may be tamer, but our boatmen err on the side of caution and look before our leap into the turmoil. Kenney maneuvers his dory with such finesse that 20 seconds later, we are at the end of the line and bailing the few gallons of water that splashed on board.

We’re traveling now on the back of the wild tuna. Surfing waves, skimming surfaces, darting into the depths. Tuna Rapid isn’t a snarling current of ferocity; it wasn’t one of the “rapids of consequence,” but the name is fun. Stepping off one fish, we saddle up to ride its cousin, Lower Tuna, also known as Willie’s Necktie. I am sure there is some lore regarding why Willie’s Necktie came to be named such, but for today, it will remain a mystery to me.

Finished with riding the Tuna Creek Rapid and finding ourselves below the Necktie, we are about to dip into the Jewels. Agate Rapid is so small it doesn’t warrant the assignment of a class rating. Sapphire comes on quickly, and we shoot right through it before picking up Turquoise. Three rapids in a mile and a half, ten rapids since we launched three hours and a little more than eight miles ago. Good time to stop for lunch at a small beach. The miles are starting to add up. Here we are, eight days in the Canyon, 102 miles of river covered, and all the time in the world in front of us, with an infinity of distance remaining. Anything less, and the face of the end may be seen, and who would want to find that?

Two more jewels in this rapid chain await our traverse after lunch – we’ll oblige with bellies full, returning to our pirate dories in search of the other treasures found here on the Colorado. First up, Emerald. We pass this second-to-last jewel with a loud Arrr! Only Ruby remains, but it, too, will join the booty of experience already on board the lead pirate’s boat, the Shoshone. Now, like pirates are apt to do, it is time to escape. And, as is often part of the story, the route be fraught with danger – Aye! The river ahead didn’t disappoint as it forced us to snake through Serpentine Rapid before we found refuge two miles later at the foot of the South Bass Trail in a nook called Ross Wheeler Camp.

It was back in 1915 when Charles S. Russell, a river adventurer who had plans to film the Canyon from the Colorado, abandoned this old steel boat christened the Ross Wheeler. It came to rest here at the Bass Trail after the expedition failed to accomplish its goal. This rusting hulk was built by The Grand Old Man of The River – Bert Loper. Bert is a legend here on the Colorado, born the day John Wesley Powell discovered the confluence of the Colorado and San Juan Rivers. By 1920, he was the lead boatman on the USGS expedition that would identify the future site of the Hoover Dam. Finally, in 1949, at age 79, running another self-built boat called The Grand Canyon, Bert flipped his rig in high water and died on the river he loved. The Ross Wheeler has endured for 95 years and hasn’t rusted away yet, nor has it been stolen, although that may only be due to the National Park Service securing it to the rocks it rests upon. Not too long ago, the oars, oarlocks, a cork life jacket, and other memorabilia were still found resting safely inside, but over time, souvenir hunters have all but scoured the old boat clean. Now, it serves as a reminder of two of the many legendary figures who have plied these waters.

These days, there are regulated safety procedures for commercial guides running the Colorado. The boatmen who work for O.A.R.S., the company we signed up with for this adventure, are Wilderness First Responders and Swift Water Rescue, CPR, and Arizona Backcountry Health certified. Satellite phones are carried on board in case an emergency warrants airlifting someone with a severe injury, or worse, out of the Canyon. Passengers must wear Coast Guard-approved life jackets, and a number of commercial operators are now requiring helmet usage for the more dangerous rapids. Those of us traveling in the Canyon have outfitted ourselves with the latest in technical clothing, wearing synthetic quick-dry base layers, neoprene socks to keep feet warm, waterproof outer layers, polarized sunglasses, SPF 100 sunblock, river shoes, and have access to anti-chafe, anti-itch, pain-relieving substances of all kinds to deal with whatever minor ailments may afflict us. Our food is a combination of fresh and frozen treats, from organic fresh asparagus, potatoes, lettuce, tomatoes, cauliflower, and avocados to strawberries, mango, plums, melons, apples, bananas, and kiwi. We luxuriate on baked brie, salmon, fajitas, spaghetti, and in-camp baked desserts. From the deep freeze in neatly stored ice chests, a constant supply of breakfast, lunch, and dinner meats, along with vegetarian options, emerge to satisfy our appetites. At dinner time, passengers who brought along their favorite alcoholic beverages help themselves to a nightcap or two from cold storage in the dories’ watertight compartments.

Of course, at the turn of the 19th century, none of these conveniences existed yet. Just surviving was a luxury when venturing into the unknown. The people who would dare enter into this hostile canyon to ply the wild river could see their boats dashed into kindling. Their food supplies would turn moldy or rancid, and that was only if they could rescue anything salvageable from the capsized rig. The boats themselves were an odd mix of experimentation, as these pioneers would throw various custom craft onto the river with the hope that theirs was the better solution to safely running the rapids. Safety wasn’t always attainable, from lack of life jackets to woolen clothing that, once saturated, could pull the strongest swimmers under. Death was not uncommon down here.

Back in 1869, during Powell’s famous journey down the Colorado, three men, fearing the worst was yet to come, left the river at mile 239.8, never to be seen again; today, that location is called Separation Canyon. Brown’s Riffle at river mile 12.1 notes the death of Frank Mason Brown, who, back in 1889, led a group surveying the Canyon for the purpose of establishing a rail line next to the river for moving freight. From the same group of surveyors, Peter Hansbrough’s boat flipped a couple of days later, killing him and a cook’s helper. A few months later, Robert Stanton, who had been on the earlier trip, found Hansbrough’s body at mile 44; that location is now known as Point Hansbrough. There are other spots noted for those who sacrificed all in trying to forge a way and a name out of their bravery and curiosity. I have to wonder if these souls were truly out to explore the world or if they were on a larger quest to explore themselves.

An interesting side note regarding Robert Stanton: on that fateful trip with Brown, following the death of Hansbrough, it was decided to hide boats and gear in a nearby cave, allowing the survivors to hike back to Lees Ferry on an old Indian trail. This cave would prove historically important many years later. In 1934, Bus Hatch, another river pioneer, found a split twig figurine in Stanton’s Cave. Twenty-nine years later, Robert Euler working for the National Park Service as an anthropologist, uncovered another 165 of these figurines in the cave, dated to be about 4,000 years old. We passed that cave back on day two near Vasey’s Paradise.

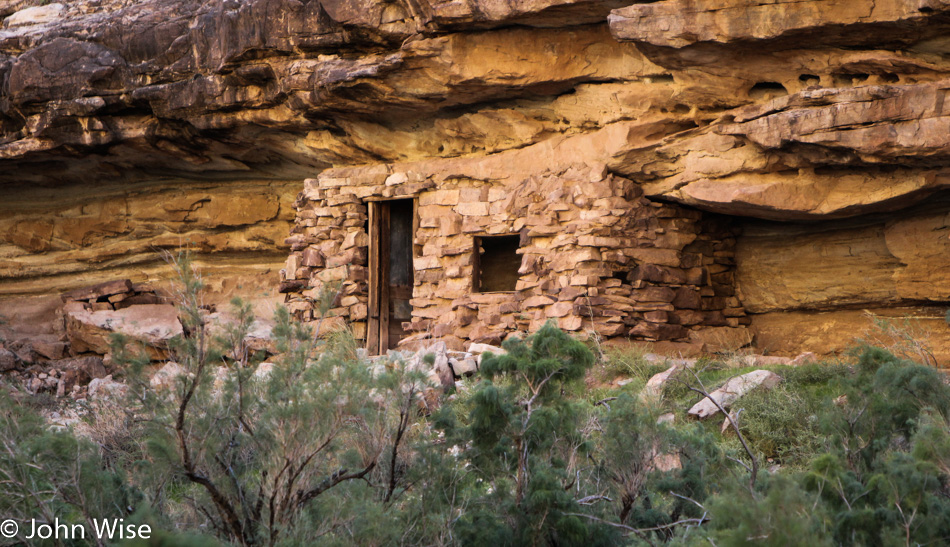

We walk away from the steel hulk of the Ross Wheeler into the shoes of another trailblazer out to explore his world – William W. Bass. While the Ross Wheeler stands relatively strong on river left, the remnants of William Bass’s tourism operation in the Canyon are in ruin, rotting as the processes of erosion claim what’s left of his camp and aerial tramway crossing. A more enduring reminder of Bass’s presence is the more than 50 miles of trails found scraped directly on the surface of the land his legacy is attached to – it is called the Bass Trail. Back in 1883, Bass started giving tours of the inner Canyon and began construction of a path that would bring tourists on a cross-canyon trek connecting the North and South Rims.

It is already late in the day when we take off from camp to have a look up the hill, so we must move fast. We spend a short time inspecting the crumbling walls of Bass’s small stone cabin, not far from the river. Over the ledge, part of the tramway assembly Bass used to ferry visitors and supplies over the Colorado, connecting the North and South Rim trails, can be seen. Across the river, a notch is the only reminder of where the cable was once attached. Our group, led by Jeffe, is small; Caroline and I make it even smaller as we stay near the cabin while the others go on further for a better view of the surroundings. We meander along another trail back in the general direction of our camp. On our way, we find the remains of a second small building, which may have been a shelter. Part of its fireplace still stands, looking as though we could toss in a log on a cold night and make a nice camp here. Under any other circumstances, the stuff strewn about this ruin would be called trash, but the National Park Service deems that effects left here more than 50 years have historic and cultural value and should remain undisturbed. And so, the rusting cans, nails, and various other artifacts sit under the desert sun to remind us, in ways both large and small, of the others who came before us.

Standing here, at what was William Bass’s camp in the Canyon, and looking out in all directions upon the desert, I would like to know who this man was. What kind of fortitude did he require to find life’s purpose through the goal of carving foot trails across this Grand Canyon? What is it that ignites people’s passions to give their all in order for others to share in finding their own potential in the vastness of nature? In a future age, will he be seen as a John Glenn or Bill Gates, extending the view of the possible? His name hasn’t survived like John Muir’s. We don’t celebrate his vision as we do Ansel Adams, but I, for one, would like to recognize the efforts of William W. Bass in giving us one more avenue to perceive our world from this remote trail he cut over a hostile and beautiful landscape.

–From my book titled: Stay In The Magic – A Voyage Into The Beauty Of The Grand Canyon about our journey down the Colorado back in late 2010.