We are on the road to Tenejapa, Mexico, or are we on yet another road into ourselves?

There’s a lot of beauty out here and much to explore, but an infinite amount of time is one thing we will not find while we drive through small towns along the way to places that are part of our life adventure.

This day will stand out as one of the most difficult to convey the magnitude of the experience we moved through. On one hand, it started like any other day: one moves into exploring their world on vacation, but as time went on, things went into depths that culminated in an emotional morass, leaving me unable to fully comprehend how I was taken so effectively into the corners of myself.

The idea of a starting point is futile as it’s the continuum of me that was entwined with something extraordinary in the environment and culture that I became a part of today. The linear narrative is relatively easy when waking is followed by eating, is followed by going, is followed by experience. But this day isn’t a string; it’s a braiding, an entanglement, a weaving. We are the parts of the loom. The land, people, and culture are the warp, and we are the weft.

Now, my work is to help my reader share in our journey without me simply saying we went here, bought that, saw those things. Yet here, in the first minutes after our return in the late day, I feel that my thoughts and emotions are so jumbled that I can’t really tease out why I believe I can or should attempt to write about any of this; it was that deeply personal. Of course, this was complicated by the fact that on the second day among the indigenous people of the Chiapas region, we have moved away from an international city and into something that requires some reflection.

I can’t show you my heart, have you feel my tears, or walk into my senses. My photos pale in comparison to the instant of reality as it was experienced, and they disappoint, although maybe in the time to come, when we glance back in remembrance of what we may have forgotten, these captured impressions will reignite a spark of what was brought into our beings today. Mind you, I cannot obviously speak for Caroline, but I do believe our synchronicity has often tied our experiences into something very similar and that through these missives, I’m able to bring her back along with me.

Today we often moved separately, walking with others from our group, which probably was due to my wandering away from everyone so I could filter out the American experience and be in the center of the Mayan universe. I don’t mean to imply I can know it as any Mayan can, but from my cultural perspective, I was jettisoned into the profound, which was as immense as the Grand Canyon and as far away from my normal as taking off to visit the Orion constellation.

Though there may have been some physical distance at times, we are always together, and if I leave this corner of Chiapas with nothing else, it might be that the Maya are still together, still here, just like Caroline and I with our personal relationship. Their culture evolves too, but love is flowing in their faces, in the smiles for their children, in glances that show uncertainty about us outsiders, and the order of need to exist together.

I’m struck that after 7,000 years of growing oranges, they still look exactly like oranges, and yet each of us humans wants to take pride in our uniqueness. While controversial, I don’t really believe we are so unique. Just as some oranges are sweeter or sourer, some humans are wiser, and others are happy in a simple existence. The problem for me are those camouflaging as something sweeter than they are when their bitterness or hostility shines through to those who are observant.

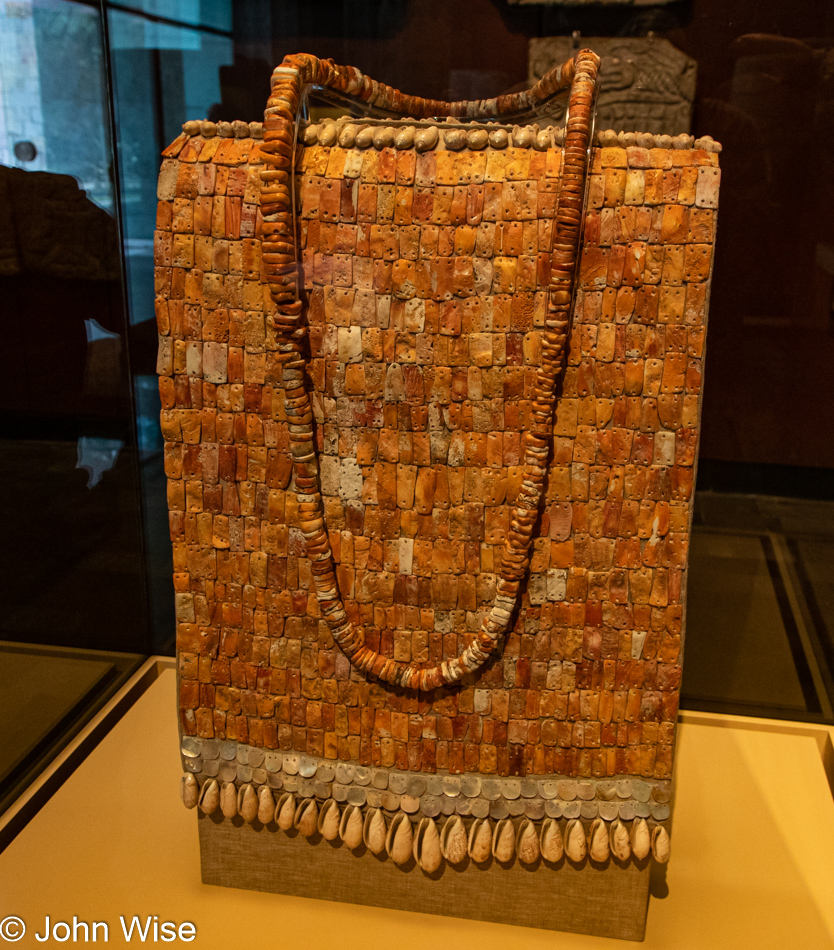

This photo of a wife, a wife named Caroline, my wife, is that of a nerd who is geeking out right now on a bag she’s now the owner of. She can relate to it because her knowledge allows her an insight into the process used to make it, which she believes is something akin to sprang. Caroline knows sprang because she learned the basics about this form of braiding in a workshop and is still trying to learn more from books or the Internet (as a matter of fact, there is a half-finished scarf sitting on her sprang frame at home). In her face, I can see the genuine happiness of a person who is sweet and full of gratitude for the creator of the bag that is now in her possession. Caroline is a sweet orange, not a sour lemon. Speaking of plants, these traditional carrying net bags are made out of ixtle (agave) fibers, which are spun into strings. The bags used to be carried over the head with a leather strap or tumpline (sometimes sold separately), but that is rare nowadays when you mainly see them slung over shoulders.

Trying to get photos of the people of Tenejapa is not easy as they’d prefer that nobody takes their photo, though I’ve seen friends and family taking snaps of each other. So, I have to be quick and try to take photos in a direction that doesn’t appear like I’m focusing on any one person, but there are a thousand faces I’d love to study. The inhabitants of this village speak Tzeltal as their native language, but I’m fairly sure that many likely speak Spanish, too; then again, I really know little.

While many people walking by are in jeans and flannel shirts, there are also many people wearing variations of Mayan traditional clothing. Here we are still in the marketplace where Caroline picked up one of these belts, and if conformity of American business dress wasn’t so rigid, I’m sure she would have picked up a dozen other pieces here.

The smoke from fires dot the landscape, often used for clearing land for farming, though some plumes are from kitchens using open wood fires for cooking, or in other cases, someone is burning waste. The haze lingers in the valleys and in front of the mountains.

A Mayordomo, the man in the red shorts, black fleece, red and white sash, and cowboy hat, is, in a sense, the local policeman. He is the man in charge, and we saw many of them wandering through the market. I asked one for a photo, he declined, just as I was told they probably would. These officials don’t carry weapons, but their comportment lets you know not to take their authority lightly.

Only calm babies and infants need apply to ride a rebozo wrapped over their mom’s shoulder. The rebozo is really nothing more than a shawl with dimensions of about 6 feet long and 2 feet wide. Mayan children seem quite content and not very fussy while they are snuggled up to mom’s chest or quietly sleeping wrapped up on her back. Looking for what I could share about this ubiquitous textile article we are seeing again and again, I learned how they can be very helpful during pregnancy and childbirth; click here to read the article I read.

Every man in Tenejapa must contribute at least one year of community service; as a Mayordomo, you have greater responsibilities, and the lead guy will carry a stick to show his position. It seems like we were told that the top guy is also provided with a temporary home to fulfill his duties. When his term is over, I thought I heard it was three years; he vacates the house and returns to the family home.

Slow down, we have. Leaving town proper, we are going out into the Tenejapa municipality for our next visit.

Almost there.

We’ve arrived; time for a Coke.

Just kidding, we are visiting world-class master pom-pom maker Feliciano Méndez Intzin. He’s on the right, while his wife, Concha, is on the left. We are about to get a lesson in pom-pom making, which you’ll see in a second,

First, we were introduced to the rest of the family, ending with the newest addition to the family, her name is Ximena. I think it was with at least a little bit of irony that we were told that this baby girl may never need to walk on the earth below her feet.

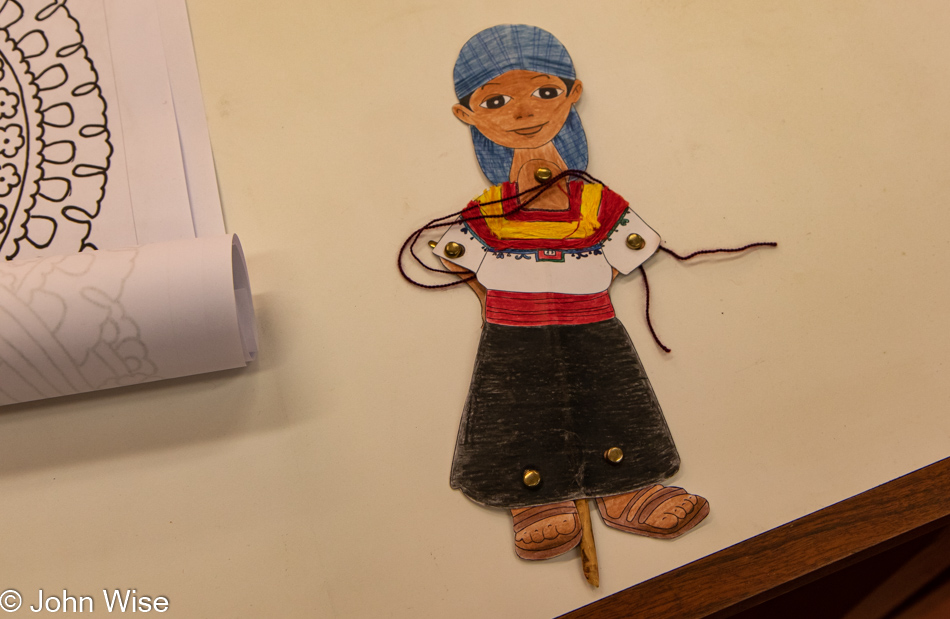

On to the pom-poms. These are some of the newest additions to the traditions of a people who are flexible enough to adopt flourishes and flair that may not date back thousands or even hundreds of years, but they look good, so why not go with it?

Hanging from the hat, this adornment adds another layer of regalness to an already commanding traditional attire.

We have all gathered in the family’s workshop, where they come together in an effort to make the pom-pom that apparently has become an important addition to their income. These chords you’ll see in the photo above are what the pom-poms hang from and are another handcrafted part of the decoration.

Concha’s work is seen here as she knits a soft exterior over a stronger rope core until she’s produced lengths of chord, as seen just above this.

As not all people want such vibrantly colored pom-pom and would prefer more earth-toned subtle hues, the family also dyes their materials using all-natural dyes derived from indigenous plants.

The proverbial bug sitting snug in the rug, except this, is beautiful little Ximena with her pink fleece wrapped up in grandma’s rebozo.

First the lessons and demonstration of craft and then onto shopping.

We have absolutely no need for pom-poms, but that doesn’t mean we have no desire to support the continuing efforts of people who are extending unique colors and additions to the dynamic changes that are nearly always moving through societies. As Caroline points out, while she has no idea what we’ll do with these when they get home to Arizona, they feel nice and well; that’s good enough.

While the shopping continues, I head out to explore the front yard and details streetside, aside from the little grocery and Coca-Cola stand we parked near.

The warm, partly tropical climate makes for a lush environment, and when the sun comes back out, I have seconds to capture some of these images.

We are on our way back into Tenejapa proper.

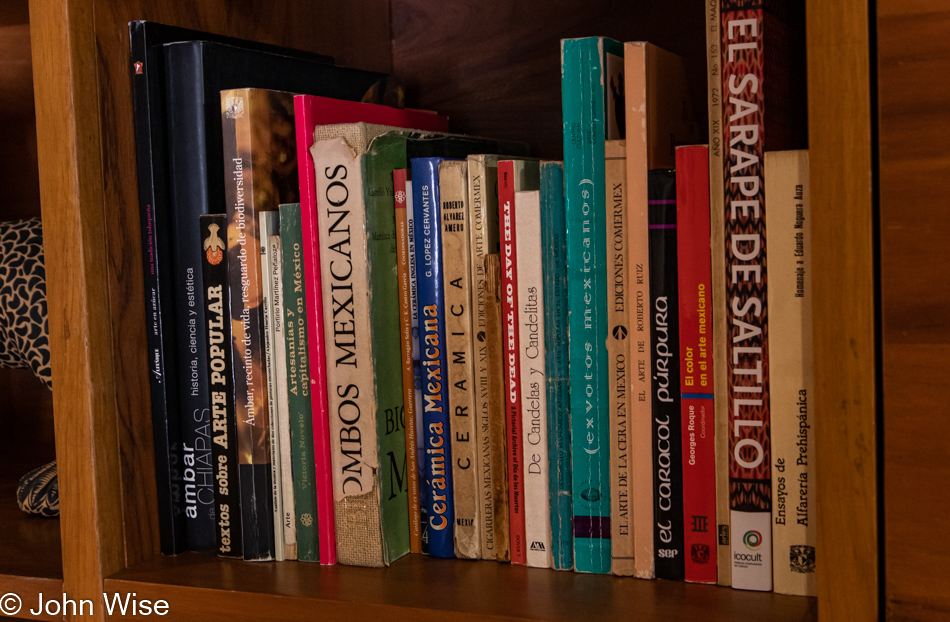

While not relating specifically to textiles, this side room of the next business we visited had an aesthetic I found appealing.

This is the Cooperativa Mujeres en Lucha or Cooperative of Mujeres and Lucha in Tenejapa. Coops play in incredibly important role for women in the region as they cannot all afford storefronts nor hope that the random traveler might pass their door and know to stop in.

Meet our tour organizer, Norma Schafer. She’s an incredibly enthusiastic and passionate woman whose sense of sharing and personal insight will continue to unfold and impress me over the course of this lesson in humility.

And now a photo of our smiling interpreter/guide without a mask, Gabriela Fuentes. We all encouraged her to buy this shawl, telling her how nice it looked on her, but maybe she’s playing it smart by collecting photos of herself wearing all of these exquisite clothes, looking glamorous and beautiful while saving her money for other important things.

On the road to Romerillo, I passed a guy checking out his social media, or whatever it was he was doing with his smartphone.

In Romerillo, the traditional clothes of men include these woven, felted, and brushed white tunics. After returning to Arizona, Caroline informed me that the people of Tenejapa have their own traditional attire and customs as compared to the people here in Romerillo, who are part of the Chamula tradition.

We have stopped here in town to have lunch among the dead in the local Mayan cemetery. Just as this entire trip is a series of firsts, so is eating in a graveyard. Should you find it peculiar, we are not the only ones who have done this in the past, as evidence is seen next to crosses where bottles of coke or oranges have been left for the departed.

The white cross is from an infant, the cross behind it, barely visible, is another infant, the three blue crosses are from young to middle-aged adults, and the black cross in the back is from an elderly person. The remains of the deceased are never removed from a grave; a room is made for the next person from the same family that is being interred.

Twenty-three crosses represent the 23 surrounding villages that are allowed to bury their dead here. The particular tree called the Chiapas pine growing here is becoming ever rarer, and while important to funerary rights in the area, it may not always be around to fulfill that tradition.

This is Alejandro who has met us at the cemetery and will guide us to his family home up in the hills.

Just beyond the family running across the street is Alejandro on his motorcycle leading the way.

To the best of my ability to identify features on satellite images, I believe this is the Iglesia San Sebastián Martír (Church of Saint Sebastian the Martyr) that was passed on the way that would take us up a dirt road into the woods.

Moving into the woods, I just promised.

Yep, in the forest.

Our path took us to the right, where we were about to meet Alejandro’s family in the unpronounceable village of Chilimjoveltic.

It is very uncommon for the Mayan people of this area to allow themselves to be photographed, outside tourism is still very new to them. They fully understand that those from the world beyond their towns have the means and wealth to come visit poor, simple people for some strange reason. This is just their life; it is not theater. The incredible honor to be allowed into their existence, even if for only an hour or two, is something that has touched me in such a way that even writing this right here the next day stings my eyes and makes my cheeks flush with how wonderful the gift is they offered us. This is Alejandro’s mother on her way to greet us with a hug; her name is Maruch.

Give love, receive love.

This is Maruch’s sister, Mikaela.

Another member of the group today asked me here at this family’s home what was likely a rhetorical question but it did make me think about why such a thing would be said. The question was, “Why do you think people are buying stuff so rapaciously?”

When I woke up the next day, I found this question at the front of my mind, and what I came up with was that when people feel that an experience or sharing is giving them everything and more, the sympathetic human response is to share your own good fortune with the other person. So, in the context of this adventure into the fibercraft world of southern Mexico, there are many of us who feel that immersion into novel experiences is more valuable to us than the cost of entry, and so we need to give back. When a person who obviously has little to nothing invites you to share their food, it’s difficult to accept their generosity, and that triggers our desire to somehow give back to them. In the photo are Loxa and her daughter Edna.

If a sociopath is involved, they might think they deserve your last crumbs and that, due to their apparent status over those around them, they are simply collecting what is due. If a narcissist is present and is not allowed to be the center of attention, they may act like a petulant, spoiled child and want to take their toys away until the other child begs them to stay.

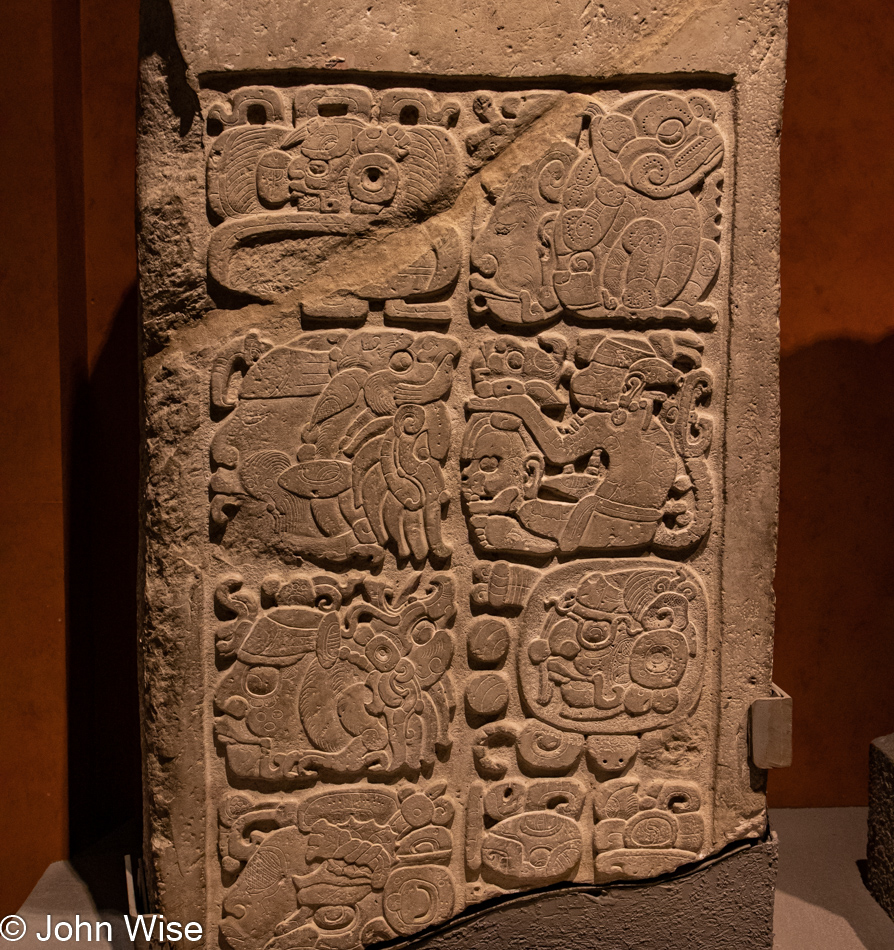

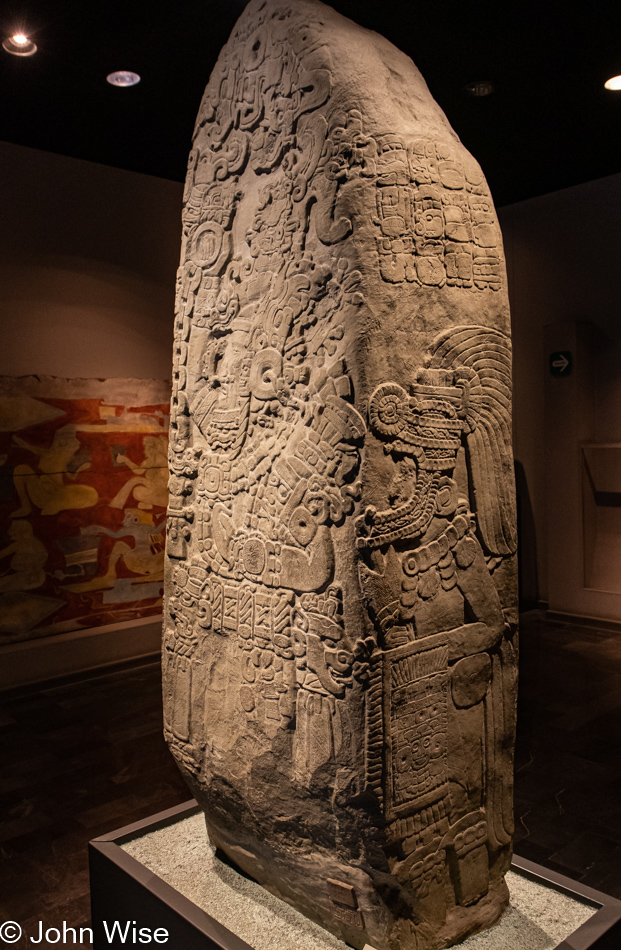

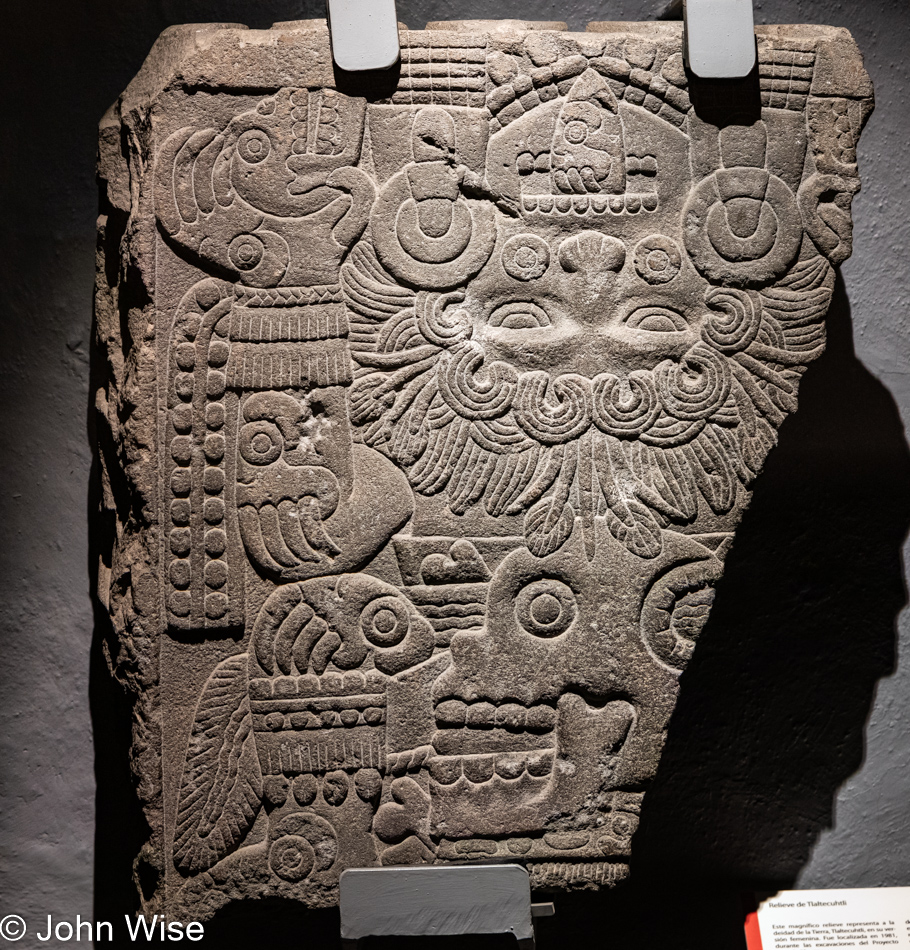

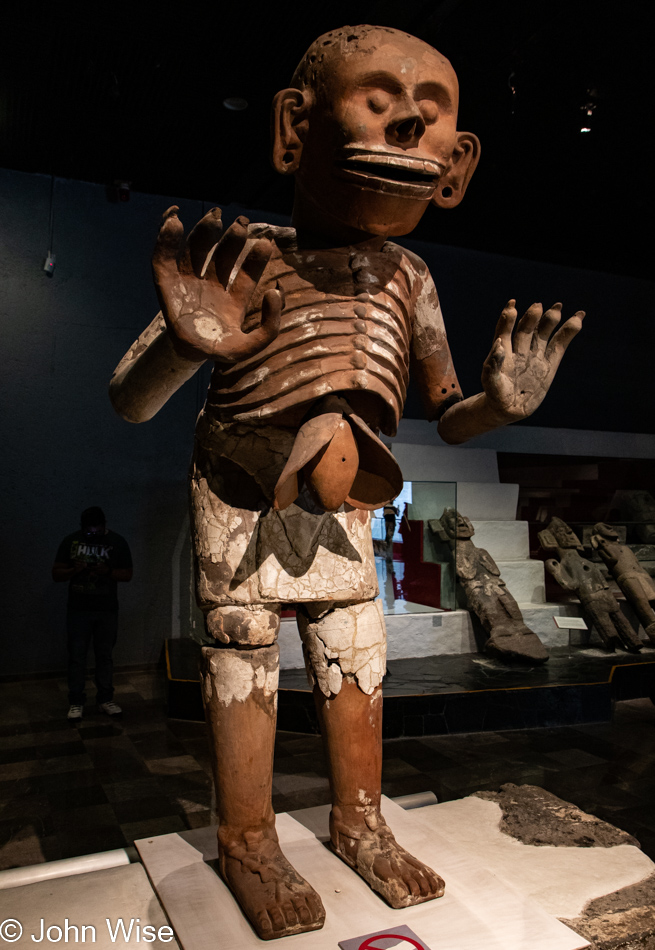

This then brought me back to Teotihuacán and the history of human sacrifice there and here among the pre-Columbian Maya. If your culture understands that God gives you life and afterward takes it back into its kingdom, then offering some of those lives early could be a way of showing appreciation for the good fortune the society has been experiencing. In a culture that has nothing of power or substance to offer gods, what then is more precious to give than life?

We in this age who have deep empathy and recognition of what is afforded us when others who are less fortunate share must find a way to honor our hosts/gods. Here in modernity, the non-violent way of making this sacrifice is to give money, gratitude, and smiles. Showing humility, graciousness, and offering yourself, family, home, drink, and song when that is all you own deserves respect and maybe some kind of offering from the visitor. From those of us who have the obvious means to take ourselves around the world who walk into a culture where paying for education, finding healthcare, or even traveling 50 miles is something afforded to a tiny minority, we who arrive to witness this must give something in exchange for hosting us.

Again, this is what I see in those pre-Columbian cultures who desire to give to the gods what the gods gave to humans: their lives offered prior to growing old as a form of exchange to say thanks. So, the reason we buy “so rapaciously” is that we recognize the honor we have received of peeking into the daily lives of people just trying to survive while we entertain ourselves at their expense. What possibly could we offer them of any value for enriching our lives than to try within our means to enrich theirs in some small way?

The young man above is Edgar, son of Loxa, and the maker of this bag that says, “Peace” and “I Love You.” This is the very first piece of fibercraft that I bought specifically for me on this journey. I was honored to offer this young man a little something for sharing something from him with me, a man he doesn’t know and can never know.

Mikaela is seen here spinning wool into yarn…

…while Loxa is combing fleece so it can be spun.

Raw fleece that is destined to be carded, spun, and finally woven on a backstrap loom that will become an article of clothing.

Maruch working the widest backstrap loom Caroline has ever seen.

Notice the string behind Maruch’s back; this is how tension is added to the loom to keep everything taught enough to create patterns.

Edna is learning early what the adults around her are doing.

From the sunflower family of plants comes Ch’ate’, as we’ve seen it named the following day at the Na Bolom museum, but after some serious digging, we’ve come to believe this is known in the west as Ageratina ligustrina, also known as privet-leaved snakeroot. This plant is boiled in an iron pot to produce natural black dye.

Caroline might be so lucky to have the opportunity 2 or 3 times a winter to wear something this heavy. That’s Loxa again, and she’s the weaver who made this heavy-duty huipil.

After the demonstrations and shopping, we were invited into a larger room where we were gathered around a table for the group’s first taste of pox, pronounced posh, a strong liquor made from sugar cane and corn. After the ladies set everyone up with a chair and a small glass, Alejandro and Edgar took up a place across from us.

The final heartstring snaps as the beat of the guitar, drum, and voice sends me outside, with emotions no longer able to be contained within me.

Gazing out on the Mayan landscape from my seat on a log here in Chilimjoveltic, I see in the haze a place of great intimacy for those who have known these lands for thousands of years. I cannot see what they know, nor can I hear what they’ve heard. The song I can still hear from nearby only hints at incomprehensible knowledge and customs as I sit here alone and weep.

Pox is a distilled corn spirit for ceremonial use and special occasions; this is one of those moments…

…and then minutes later the world returns to silence until the cycle starts all over again.