The layover is over; time to leave Lowell Lake. As we paddle westward, it is a strange thought that our departure is hinging on finding a way through the ice. If the passage is closed, we either wait, or we portage. Lucky for us, we are able to find a thread to follow and are soon moving right along. It is a bittersweet moment. I was just getting a faint sense of Lowell Glacier, and now this might be the last I ever see of it. Disneyland, the White House, Yellowstone, those all feel easy to visit. They are relatively close and can be visited nearly on a whim. The Alsek is not traveled to and on as a spontaneous decision to just get up and go. Here we are in the third week of June, river season barely started, and in less than 90 days, winter will be greeting the stragglers who venture onto the river late in the year – way out in September.

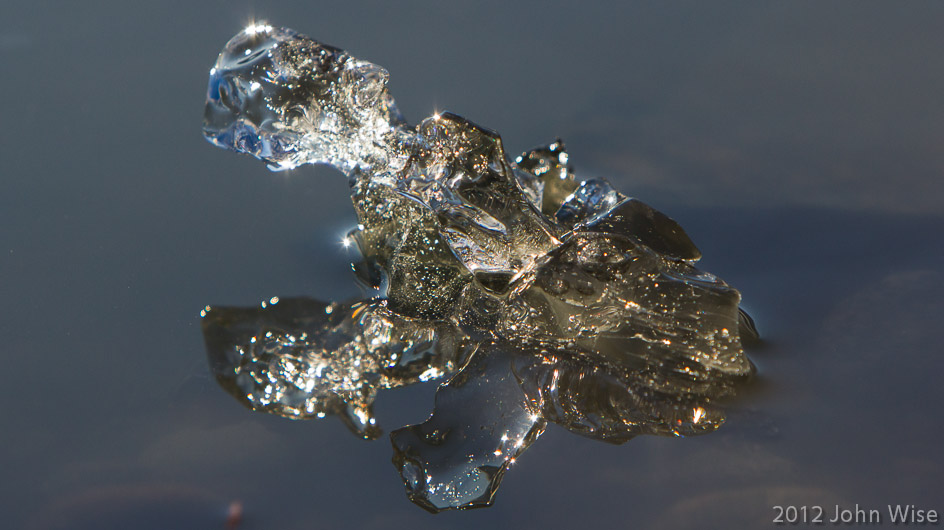

We don’t get far before the guides decide it’s already time for a hike. Our landing spot is on the west side of the lake; the idea is to hike to an overview of Lowell Glacier so we will have the opportunity to “See it all!” Familiarization with one location often tricks me into thinking that the rest of what’s to come will be quite similar to where I’ve already been – wrong. We exit our rafts on what at other times must be lake bottom. I imagine that the pools we are seeing are one of two things: either they are depressions that hold lake water from waves that spilled into them, or second, maybe icebergs were stranded here as the lake level went down, and this is its meltwater.

We don’t have to walk far before the perspective change is so dramatic that I’m not sure we are still in the same relative location. Pay particular attention to the steep gravel hillside on the left of this photo; that is where we are heading. I’m confounded in places such as this; my thoughts are asking, “What’s wrong with this location?” I understand there may be something of special interest just over the hill, but when do I get the time to fully absorb this place? That giant mountain on the right is Goatherd Mountain, which the majority of our group hiked yesterday, with a few of the hikers making it nearly to the peak.

Funny thing about perspective: if I were a cell of bacteria, this yellow bloom might represent the majority of the universe I would ever know. As a human, I look out and try to comprehend my scale in comparison to what is extraordinarily large, such as glaciers, mountains, rivers, and the distance to a horizon. But that is often as far as we choose to perceive ourselves. What happens when we try to find scale when looking out into the universe? Do we somehow still believe that our star-speckled evening canopy is mere miles above us? Could we think it is just out of our reach, and so it’s not too threatening? And what of this tiny bloom? Is it too small and insignificant to demand our attention? How did the others walk by as though it didn’t exist and yet were so enamored by the largeness they were taming? Maybe that’s it; we believe the tiny has already been conquered and that taking control of the immense gives us a sense of power. So what of the thing that cannot be seen by the naked eye, the microbe, the mutation in our DNA or cell, or radiation that we do not control? A word of advice: When in the big, don’t forget to stop a moment and enjoy the small; it too can be immense.

What one doesn’t see in this photo is the tiny strip of trail between me and those hikers that has my vertigo saying, “No way, buddy, you’ve gone as far as you will today.” Caroline decides that she’ll trek back with me to keep me company while Bruce hands off a can of bear spray so I don’t have to try taking out a charging bear armed only with my camera. With Caroline acting as bait, we amble back to the rafts. The going was slow. The only problem with that was during the slowest progress forward, we would also be the quietest until we realized that a bear could be on the other of nearly anything around us. Time to sing. Somehow, Caroline must think Irish folk songs would keep the bears away; I’m thinking, “Well, maybe. There is that story about Ireland and snakes; come to think about it, have I ever heard about bear attacks in Ireland?” This could work. Seven Drunken Nights is the tune, and it goes like this:

As I went home on Monday night, as drunk as drunk could be

I saw a horse outside the door where my old horse should be

Well, I called me wife, and I said to her: Will you kindly tell to me

Who owns that horse outside the door where my old horse should be?

Ah, you’re drunk,

you’re drunk, you silly old fool,

still, you can not see

That’s a lovely sow that me mother sent to me

Well, it’s many a day I’ve traveled a hundred miles or more

But a saddle on a sow sure I never saw before

With Caroline singing bear defense songs, I was free to turn my back on danger and focus on the easily unseen details. Granite with green lichen is a sight we don’t see every day. Well, some readers might, but I’ll bet they don’t see it with a giant freaking glacier on their side with the chance of being eaten at any moment by a fearsome grizzly bear that is probably stalking them right now. The other hikers are out of view, the rafts cannot be seen from where we are, and neither can the conspiring bears that lay in wait. Crank up the sixth verse, wife, and get on to singing about those two hands on her breasts that Saturday night when old, what’s his name, was drunk as drunk could be.

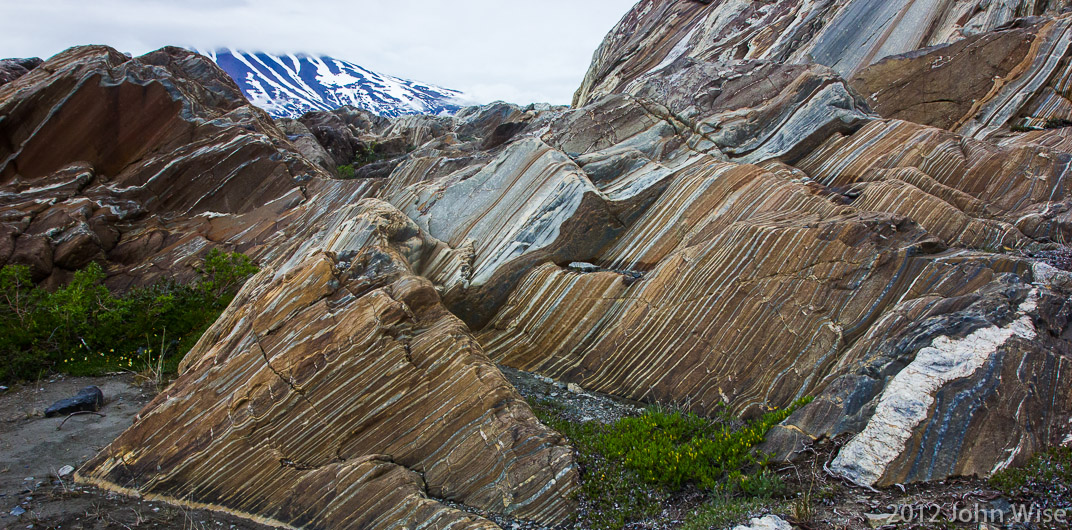

This beautifully colored red and orange rock grabbed our attention because it looked as though it had been struck by lightning. There, I heard it again. A noise in the underbrush has piqued our curiosity. What is that? A bear cub? No, it’s a full-grown moose about to stomp on us! Just kidding. I said, “Underbrush,” it was a bird. A very aggressive one at that. Each time we’d try to peer through the leaves, this invisible bird would flutter about, making a lot of noise, but never an appearance. Maybe it had chicks and was defending the nest; we quickly moved away to leave the bird to its parenting chores.

In the beauty of this glaciated land, even death and decay take on aesthetic qualities worth noting. Back on Day 4, we passed a moose skull that was an art piece in its own right. Today, it is the remnants of these flowers that tug at my curiosity and sense of attraction. The stems are nearly monochrome, with only hints of the golden yellow that for a very short time came into existence giving us a hint of what this scene may have looked like just a week ago.

Five cascades are on view in this photo. The mighty Alsek River is running up at the base of those mountains. The scene is enormous, but it is hardly a very wide panorama; it is but a fraction of what we were looking at as we turned from side to side and looked behind. Caroline and I are near the end of our hike back to the rafts. From here, we turned left and descended back to the lake bed for a quarter-mile walk to the lake’s edge, where the rafts were tied down. The third picture down from today’s blog entry is what’s behind us. Between the two photos, you are seeing about 60% of the view. To see it all would surely bring you to your knees, as it did us.

Goodbye, Naludi, you’ve been terrific. With Lowell Glacier quickly fading behind us, it is now time to turn our attention to what lies ahead. The only problem is there’s really no way to know what is further downstream. Wild animals, weather, an iceberg, or an earthquake could change everything. Maybe the lay of the river has been altered, and a new unrunnable rapid formed over the winter? We’ve already heard about the difficulties entering Alsek Lake towards the end of the journey; it is not unheard of to find ice blocking the entry points, forcing passengers and crew to lug boats and gear overland to complete the trip to the Pacific Ocean. Right now, though, none of that matters. This beautiful day suggests to me that this adventure will be nothing less than perfect.

I posted it because it’s pretty.

Little stones, big rocks, giant boulders, hills, cliff-sides, escarpments, and towering mountains that reach for the heavens are being broken down to pebbles, grains of sand, and finally silt. The components that make up much of the earth’s land surface are in a near-constant state of flux here in this corner of North America. Nothing is safe here from being ground down, tilted, shifted, thrust forward, or upward – the Earth is actively at work here. So I may be repeating myself here, but I am so taken by this idea that hundreds of millions of people might see the same movie next year, but I will be the only person on earth to have ever touched or seen this rock in person. Well, that just leaves me in astonishment as to just how big our world is, while our existence within our urban zones is so tiny.

After arriving at Sam & Bill’s to make camp, the first order of business is for us to unload the rafts. Then, it’s time to pitch our tents. With our sleeping arrangements in order, Caroline and I took a walk along a nearby stream. We didn’t go far due to the bear tracks that suggested one might be near. This landscape defies words to describe the spectacular sights we are experiencing. The best we can do while in these moments of awe is to pretend this is all just the most normal thing we could possibly be doing right now. But it is the furthest thing from normal. By the way, our tent is set up in a drainage; if it rains, I hope it’s not a flash flood that forces us to move into the river. What I liked most about our tent location this evening was the view right here from our front door.