Rapids form most frequently at the mouths of side canyons. It works like this: when the rain comes, which it does in great sheets during the monsoon season, runoff aims for these canyon drainages that have been carved and gouged by the handy work of prior flash floods. As the rain collects and starts running over the landscape, it rapidly joins forces with a multitude of other rushing torrents, converging down the quickest path gravity dictates. By the time this deluge is approaching the Colorado, it has scoured the surfaces of the Canyon and drainages, picking up all sorts of matter, including trees, trash, rocks, and, when intensely heavy rains have battered the canyon slopes, boulders the size of cars can rush along with the rest of the rubble. This landscape scrub brush works wonders to polish canyon floors and shines slot canyon walls, but somewhere on its journey, the contents of the rushing waters are going to come to a halt. This is usually right in the main river channel of the Colorado.

Clear Creek Rapid is the first whitewater we’ll run today. Just below the side canyon we had hiked yesterday, evidence of those past flash floods has fanned out and piled up in the river, forcing the turbulent waters to find their way over a garden of rocks. As the channel becomes choked on the accumulating debris, the river finds new paths to rush through. Over time, the erosive force of the Colorado will bully these blockages into giving up territory, changing the dynamic of the rapid again. It is this ongoing process that keeps boatmen alert when approaching rapids.

Often, as we move nearer to the pull of a rapid, a boatman will slow his dory, rowing towards the shallows. Standing tall on the deck, he inspects left, right, and center. If conditions warrant, he might sing a “Hey diddle diddle, right down the middle.” Maybe a boulder has shifted since his previous trip, or a dangerous standing wave dictates if he rows left or right of center to avoid a potential boat flip. All the while, the flow, as measured by cubic feet per second or CFS, is impacting the decision process as low water can expose rock dangers not present with high CFS flows. Then, on the other hand, large releases from Glen Canyon Dam can create hazards in the form of larger waves, deeper holes, or camouflaged and hidden dangers that someone not as familiar with the river could run into, risking the viability of a boat and the lives of those on board.

With the larger rapids known for their dangerous shenanigans, our boatmen play it safe, pulling to shore to make a proper evaluation of the liquid thrill ride. Today’s rapids are read-and-run, letting our guides speed us along without stopping for riverside inspections of the tumult. Read-and-run rapids are known quantities; they are familiar, they seldom change, and are runnable at nearly all flows. The experienced boatman will make a quick evaluation, using his knowledge of the river to find opportunities that allow him to enter the rapid in a variety of approaches, offering us passengers a different perspective of how a dory can run whitewater.

Looking at our next river churner, Zoroaster Rapid, rated a mere Class 4, I try to imagine a dory-flip with me in it, allowing a more intimate understanding of the danger and dynamics of river hydrology at work here. My thinking is, better to fall into a reasonably sized rapid than to be dragged through the dreadful leviathans still ahead. It’s not that I am unaware of the potential dangers of rocks hidden just below the surface to break limbs and skulls, and the cold rushing water quickly robbing my core of heat to induce hypothermia, or that once submerged, panic may overtake the brain, elevating the danger by not following safety instructions and putting other lives at risk. I do understand all of this, but that doesn’t curb my curiosity about the worst-case scenario where I could find myself outside the relative safety of a dory. How would I react in the face of a reality where my sense of knowing what to do has been tossed into the labyrinth of chaos? Arriving safely on the other side of another rapid, I remind myself to be careful of what I wish for and give a nod to the skill of these boatmen who are creating a sense of safety that should never be taken for granted. We exit Zoroaster high and dry, with 3 miles of river left to travel before our next stop.

An easily recognizable landmark for those familiar with the Canyon bottom is coming into view – the Black Bridge, also known as the Kaibab Bridge. Built in 1928, this suspension bridge spans the Colorado, connecting the South and North Rim trails here in the Inner Gorge. Prior to this, the only way across was on an aerial tramway with a hanging “cage” that was able to move one mule or a few frightened people at a time. The Silver Bridge further downstream is the new crossing built in the 1960s. This narrower bridge doesn’t allow mule crossings, and while conveniently used by hikers, its main purpose is to support the trans-canyon pipeline that brings water from springs near the North Rim to Grand Canyon Village on the South Rim. Without it, tourism of the scale the South Rim sees today would not be possible.

Once our dories land onshore, it will be a short walk before reaching Phantom Ranch, civilization’s outpost on the Canyon floor. The trail from the sandy riverside leads up to the lush oasis of Bright Angel Creek. Living up to its name, this gently flowing creek runs clear, its surface dancing with sparkling sunshine. Our trail first branches left, then right, before continuing straight ahead. Each step forward brings into focus this idyllic corner of nature that has greeted so many visitors who embrace the grueling hike, have chosen to ride the mules down, or arrived on the river in order to visit the heart of the Grand Canyon.

Astonishment is the best way to describe these sensorial surprises that were no longer expected seven days into our adventure. It would not be an exaggeration to say that after a day or two, maybe three, one could begin to assume that we have been witness to the blueprint for all that lies ahead. After all, when seen from the rim above, each view into the Grand Canyon, from Desert View Tower to Hermit’s Rest, while certainly astounding, is also quite similar. So, as the pleasant surprises of the first days are had, each new wonder suggests that it could surely be the culmination of this phenomenon and that the remainder of this journey will be much of the same. But here we are on the seventh day, and instead of the diversity of scenery taking a rest, it is busy and working hard to demand our veneration.

It would be a lie to say I hadn’t wondered, prior to our departure, what the days or weeks down here might be like if the whole affair became mundane and boring or too dangerous for my sensibilities. Would we reach a point where hiking out of the canyon could become an option worth exploring? To a small degree, I was influenced by many a doubting friend who couldn’t imagine the deprivations we were so eagerly preparing for. They balked at the idea of riverside, out-in-the-open toilets, sleeping next to rapids in the great outdoors where wild animals may lurk, no hot water, and worse – no hot showers. They questioned the quality of food and the drinking of river water that is not only full of reddish-brown sediment but includes a small fraction of the urine of every person traveling this length of the Colorado before it is filtered and made fit for our consumption. No cell phone service or Wi-Fi, no outlet to recharge batteries for portable game machines, no bed to crawl into at the end of the day, and besides all that, we were willing to risk life and limb on precarious trails and raging rapids of bone-chilling ice water. But now that we are a full week into this 18-day river journey, leaving with a hike out right here on the South Kaibab trail is the furthest thing from our minds.

Instead, center stage is the obvious question begging an answer as to what possible reason might exist for why we haven’t been down here before. Ignorance is a paltry and feeble response; there can be no excuse to explain this oversight. A return to Phantom Ranch must be moved toward the top of the to-do list while our knees and hips are still able to carry us down and back up the rocky switchback trail. Maybe more difficult than finding the motivation to take the hike will be trying to work our way through the long wait of being rewarded a much-coveted reservation to camp down here. The closer we get to downtown Phantom Ranch, the more people we encounter. For all the hard work these robust hikers have invested in bringing themselves down here and the respect I feel for their efforts, I can’t help but feel I walk with no small amount of pride. I have been delivered to Phantom Ranch on a dory, and it just doesn’t get better than that.

Soon, we are at the front door of the canteen/gift shop, and the countdown begins – we have about 45 minutes. Passing the counter, I should have felt Caroline’s eyes draw a bead on the souvenirs and her impulse to shop, but she stayed strong as we aimed for the postcards. Seventeen of them, stamped with the message “Mailed By Mule at The Bottom of the Grand Canyon, Phantom Ranch,” are needed. Caroline takes the half destined for Europe, I grab the domestic-bound pictorial souvenirs, and we get to writing. Or at least, that was what we should have done, but all those shiny memorabilia behind the counter are floating their siren song into my wife’s ear, seducing her to their shore. Enchanted by the trinkets, she gives in and tries to leave with one of each, leaving just enough cash for one of the canteen’s famous lemonades. We then had to put pen to paper and burn ink.

With fingers cramping, we scribble to the finish line and, after depositing the postcards into a rustic mail saddlebag, scramble outside to visit the holy temple of the flush toilet. Upon entering the cathedral of lavatory splendor, my attention is willingly arrested by the left faucet handle. Could that be connected to hot water? I am certain this crazy idea could not be in the cards. Energy down here is at a premium; who would pump hot water to the facilities? All the same, it wouldn’t hurt to try. Heck, even if it isn’t heated, it might not be as cold as the river down below. My amazement overfloweth right next to the hot water that comes streaming out of cold steel into the porcelain basin. I have found gold.

Itchy, oily head, salvation is on the way. A sink-side soap dispenser never looked so good. While this is likely against the rules, the allure of alleviating the greasy discomfort camping atop my scalp is irresistible. I shove my big head as far as I can and squeeze it under the fountain of spouting hot bliss. I slosh handfuls of the worst-smelling hand soap onto my hair and almost find a lather before my rush to not inconvenience anyone who might be on the other side of the door waiting for this comfort station pushes me to rinse away the soap. My refreshed scalp allows me to feel a year younger and appear far better looking than I had in the previous days. Even my eyes feel brighter. I emerge from the john with a renewed pep in my step, delighted by my clandestine act of hygiene. Caroline swoons at the sparkle in my eye.

Reinvigorated and a degree more presentable, I try to reanimate what social skills I still have in an attempt at conversation with some hikers, who, by their good fortune, nabbed a cabin situated down here amongst the splendor. We sit in front of the canteen, which is decked out with some rather large pumpkins, begging the question, did someone carry Mr. and Mrs. Jack-O’-Lantern down here, or was a mule employed to lug their squashy largesse? We talk a few minutes, obtaining details of where everybody’s hometowns are located and how much time the respective parties are spending down here in this garden of perfection.

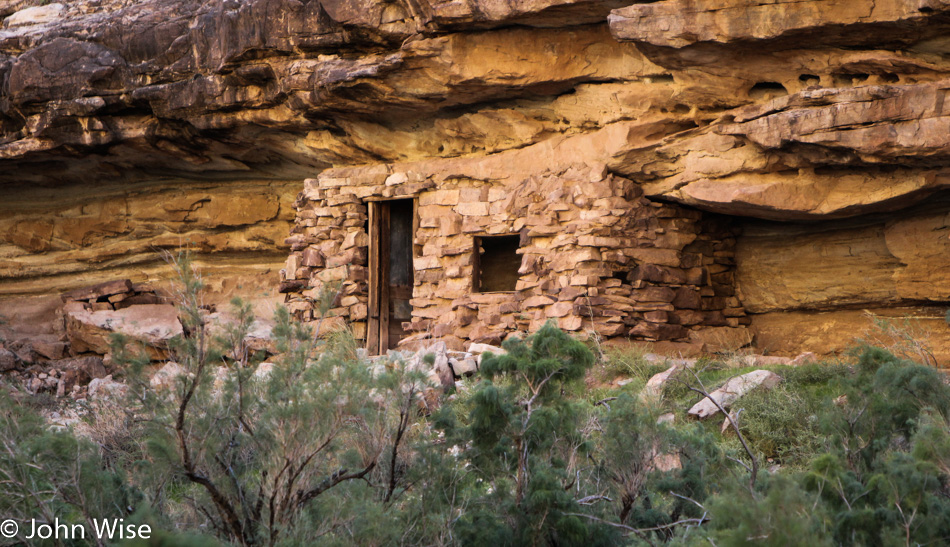

The architecture that complements this setting rose from the genius of one of America’s great architects, Mary Jane Colter. Be it up on the rim of the Grand Canyon or down here, her style graces this, the most visited National Park on Earth. It was the creative brilliance of this woman, who, after starting in 1905 with the Hopi House, would go on to design Hermit’s Rest and Lookout Studio in 1914, the Desert View Watchtower in 1932, and the Bright Angel Lodge in 1935. Back in 1922, she was the visionary for Phantom Ranch. Ms. Colter demanded that the Fred Harvey Company, the concessionaire operating the property, drop the proposed name of Roosevelt’s Chalet and adopt the more intriguing name Phantom Ranch, offering the public a more interesting vision of what lies at the bottom of the Canyon. Mystery is still attached to the name, as the camp was never a working ranch, and what inspired Colter to use “Phantom” remains unknown. It may have come from nearby Phantom Rock, Phantom Creek, the Phantom Fault, or, as some prospectors claimed, the Phantom is the mist that fills the area on cold mornings.

The noontime sun beckons us to return to the dories for our midday meal; wishes for safe travels are exchanged with the hikers, and the trail carries us away. Back on our beach between the Kaibab and the Bright Angel Suspension Bridges, between the north half and the south half of the Canyon, our boatmen have set up the tables, brought out the flowers, unlocked the secret compartment of the perpetually fresh avocado, and busied themselves to prepare a meal of taco salad wraps. Guilty indulgence is noshed on while weary backpackers unwrap energy bars. Here goes the inflating ego again. How can one not begin to feel like a millionaire when presented with this luxury and attention to detail?

In my mind, I return to an epiphany experienced a couple of years ago that rearranged my perception of wealth and luxury. Caroline and I were on our first winter visit to Yellowstone National Park. Not one to speed through the park on snowmobiles, nor familiar or comfortable with skis, we chose the more snail-like pace of snowshoeing, fulfilling our dream of a Jack London experience at the same time. Crunching step-by-step, passing Old Faithful and the Upper Geyser Basin, we cut a trail overhill and through deep snow on our way to Black Sand Basin. After our arrival there, we stood alone in the quiet of winter, the only interruptions being the hiss and gurgle of the geysers or the bubbling of hot springs. We shared a cup of tea from our thermos and looked up, admiring the blue sky and the natural beauty before us, feeling it was ours alone for this brief moment. It then dawned on me: if the wealthiest person on Earth were here right now, all the money in the world would not buy him one more moment of the incredible. He would not see any more than I do now; there is no wealth-enhanced vision to be purchased. He would be offered the same priceless view Caroline and I were experiencing. And this holds true right here, right now, down on the Colorado River in this Grand Canyon. We sit here enjoying the sights, sounds and smells that are free for all with the determination and requisite effort to bring themselves to such places, where all are equally rich from the opportunity to be somewhere special.

One might think that by now, this whitewater business was getting easier, but with each day, a new vocabulary is found to describe what we are approaching, spilling vivid detail into the imagination. We require fresh muscles to find new strength to wrestle with “the biggest yet,” “God’s own roller-coaster,” and the sublime “a personal favorite,” which can imply any level of blood-curdling thrills. Fortunately, not all rapids are defined this way. Clear Creek and Zoroaster were lively rapids, while some rapids receive no glorious name or descriptive language that braces the mind. Mile 85 Rapid is just that, a rapid at river mile 85. Horn Creek is a two-in-one ride – not only is it one of Jeffe’s “personal favorites,” it is also our “biggest yet.”

More than a quarter-mile away, and on occasion even a half-mile, we are alerted to the first sign of the watery turbulence we are rowing into, as its roar reaches us well before the sight of the rapid does. Each oar slip moving us closer also raises the volume. As the sound rolls into a thunderous growl, adrenaline starts to pump, and quick breaths of anticipation take me to a low-level panting. Then, through a cruel trick of topology that is a feature of why a rapid is a rapid, the whitewater itself does not fully come into view – the riverbed downstream is going to fall 5, 10, 15, up to 30 feet, hiding the churn beyond the first drop. So, while the boatman can stand up and see what lies ahead, our view from just a few feet above the water only allows the rare glimpse of spray shot skyward by a collapsing wave hidden down below in the growl of the agitated river. Maybe we could find comfort in seeing what the crashing water before us looks like. Or we could opt to walk around the rapid if the view of what we were about to ride through was unobstructed. Since we don’t have those options, our first peek at these bigger rapids is often had in the few seconds before the dory starts its rip-roaring ride on the bucking bronco our boatman will once again try to tame with a successful run. With helmets on, we prepare to enter Horn Creek Rapid.

And then it starts. Reaffirm your grip, scan the waves, and tune your ears for instructions. Never mind the walls of water we’ll slice through, dousing us from to toe. We are in it. Our dory shoots forward with a jolt, accelerating from a lazy three miles per hour to the heart-pounding approach of warp speed. Captain Jeffe yells from the bridge, “RIGHT,” and we high side like pros, then a sharp admonition to hold on, and we instinctually lean forward. We are tearing a path through ragged water, emerging seconds after this all began, and then the urgent command to “BAIL” pushes us into motion. A water-filled dory is a potentially dangerous dory that is unstable and difficult to maneuver. Water weighs about seven pounds a gallon; with a boat carrying an extra 700 pounds on its topside, there is an immediacy to move that water out of our craft. We are already cold enough sitting in this water; there is no need to risk a flip to place us in full immersion. We keep on bailing. Before we know it, we are pulling into Granite Camp, tying down, unloading, and are soon ready for what’s next.

The mouths of side canyons are fascinating places, starting off wide and rock-strewn, often littered with twisted trees, low scrub, and the random cactus here and there. They are gateways to magic places not always visible from the riverside. Quickly, the walls close in, narrowing the breadth of potential trails we can follow, forcing us to the most obvious and maybe only hikeable path. Trekking to the south, we have a clear view of the Kaibab Plateau, where visitors to the South Rim stand, looking out in our general direction in anticipation of the setting sun that will paint the panoramic landscape before them in deep reds and warm golden tones. Meanwhile, we are already deep in shadow, scrambling to find the trail’s namesake that will lend understanding as to why it was named Monument Trail. Our pace is quick, taking advantage of the day’s remaining light. At the foot of a steep climb, Rondo reassures us, “Everyone can do this; it’s only 100 yards ahead.” Then, just around the corner, the horizon opens again with a gorgeous view of the glowing rim far in the distance. Sunset has arrived, and so has our first glimpse of the Monument.

We hike on, crawling up the steeper and steeper trail. We go higher for the view of all views when our path splits. The left fork leads to the Tonto Trail that traverses the Tonto Plateau east-to-west, connecting hikers to many of the rim trails, such as the Bright Angel and South Kaibab trails. To the right, the fork leads to the Granite Rapid Trail. We turn right and walk a short distance to an elevated outcropping in the Tapeats Sandstone, the best vantage point to take a rest and appreciate our front-row seats for the Monument. It defies comprehension of how a tiny column of stone has managed to hold this rock highrise growing out of the Earth. But as intriguing as the Monument is, I can’t help looking back at the fork in the trail and imagine, one day, descending the path that leads to this one. The rocky, dangerous-looking route through the Canyon would return us here to stand once again in this place and remember the boatmen, their dories, and our shared time on this river.

No matter that we leave our overlook on the same trail we came in on, we leave changed, different from the people who started up the trail. What has been collected and perceived offers a new filter of how the world will be interpreted a bit differently in some small, maybe some profound, way in the future. Details unseen on the first half of our hike can now be appreciated with a clarity that enlarges and adds dimensions of beauty to the tiniest elements. Contrasts stand in force, demanding our attention to make efforts to digest what must be left behind as we move on. Did you truly see what was there? Did you hear what wasn’t? Will you carry nothing of everything that was or everything of what might have been? If it doesn’t fit in your eyes, let it enter through your ears, and when your ears can hear no more, it is time to take a deep breath; with lungs full, open your mouth and taste the experience with the flavor of life passing over your lips some will surely spill away, grab for it and stuff what you can in your pockets, and as you become weighted down and laden with this wealth, allow it to enter your mind until it, too, is satiated. Upon overwhelming your thoughts, your imagination will become impregnated, leading to a birth of awareness in your heart that your soul will nourish, leaving you the recipient of the magic of life.

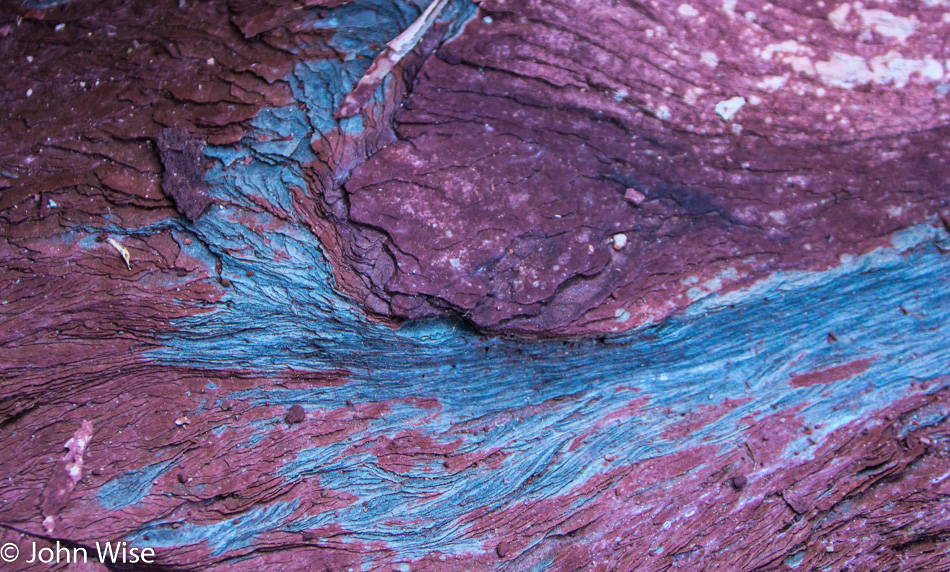

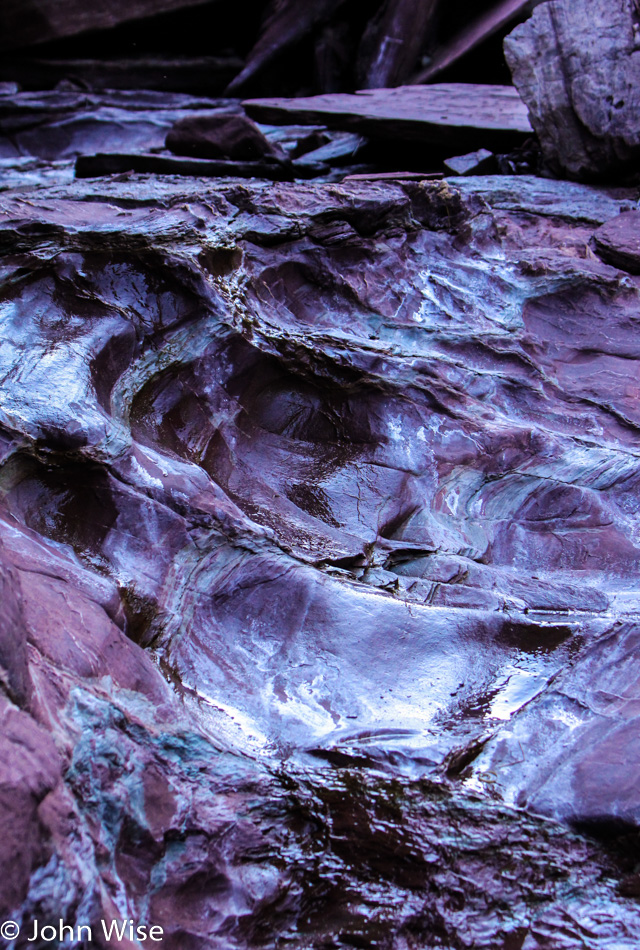

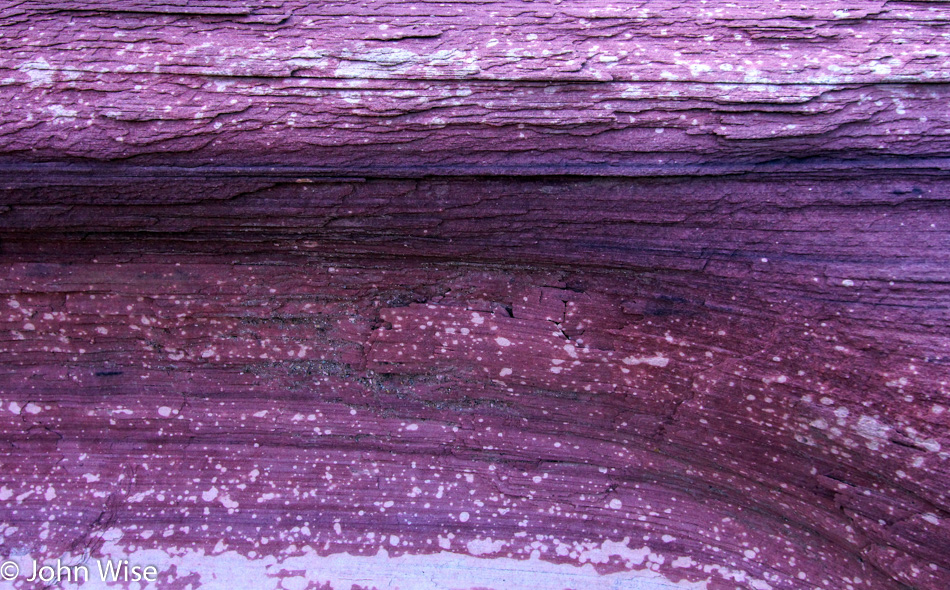

Just what is this here that so inspires me? It is the amassing beauty all around me. As the layers of sandstone, limestone, quartz, and schist form the Canyon heights, it is the accumulation of layers of beauty that are growing a mountain of indelible memories within me. Intrusions of purples, ripples of pink set against green, white swirls, and red layers of stone are painting a canvas of such size and scope that no museum will ever be able to play host to such majesty. Should you dare to see this, to really see what is here, you will surely celebrate the geological ecstasy our living planet has given us, just like I am now.

Try not to think too hard about where else on Earth this kind of environment could exist, for you will find yourself wanting to explore it, too. A large part of this path of natural beauty has casually been destroyed by a constriction of cement erected to dam the Colorado north of us. Lake Powell’s waters have buried Glen Canyon and stolen its untold cultural and aesthetic wealth. For now, we will have to be satisfied that this small stretch of wild river we are on still exists. We can dream of how many more side canyons may have been explored and shared with an even greater number of people if the Colorado were still navigable from above Moab, Utah, all the way to the impounded waters of Lake Mead standing behind the Hoover Dam. Better still, we could wish the entire Colorado River system could one day run free.

A book should be dedicated to the poetry not yet written of the side canyon Monument Creek runs through. A proper inventory of each and every object that gives this unique location the character that, in concert with stones, jagged edges, twisted forms, and amazing wild history, offers a visual symphony never before performed for my senses. Do not make the mistake of looking through jaded eyes. Peel back the layers of your age, go back, and find the eyes of your youth. Remember when our vision was not obscured by the definition of what our mind saw when, down on our hands and knees, we could find the grandeur of a universe in the sandbox of our local park? For all that has changed over the years, for all the aches and pains, the gray hair or extra pounds, whatever level of education was attained or successes found, from the time we weighed but seven pounds until now that we are aware and “in charge” of our lives, there has been one constant, one part of us that may be weaker today than they used to be but are the same size and shape as they have been since our birth – our eyes. Let us use them, but not as though they were well-worn, all-seeing, know-it-alls. Let’s wash away the clutter of everything familiar and look at our world through new eyes, through the eyes of innocence, through the eyes of the child.

The scenery here is not composed of “just rocks” these stones and sands are part of the soil of Earth from which we came. Their elements are a part of our very being. Millions of years ago, they were a part of the Earth that gave rise to a plant that, in our day, would become part of the dinner we eat tonight. The water flowing next to our path is part of the water that has always been on our planet; the water our ancestors drank from is here. Their hands scooped from a stream to quench their thirst, and what slipped between their fingers rejoined the waters that I would drink from a thousand years later. Today, we are walking on rock, sand, and dust; once gone from this life, we, too, will return to this dust, offering ourselves back to earth. Our bodies will rejoin the soil that is the medium of growth for a large part of that which sustains life. This cycle has played for countless millennia; nature knows its song, but in our age of modernism, we have not developed a sense to dance to this tune of harmony. Today, we should make that effort to hear the music, see the beauty, feel the unrestrained world, and embrace the delight in knowing we are alive.

What do we do when we find ourselves in nature, in a place we couldn’t imagine being a few hours ago before someone guided us this or that way? Crashing through Horn Creek Rapid earlier in the day, we couldn’t know for certain that soon we would be hiking the Monument Creek Trail. Had Granite Camp been occupied, we would have continued downriver, searching for another site to rest our heads and bones. The trails found at that other site may have taken us to heights that could eclipse the awe found here, or maybe the essence of the amazing is in everything around us. We only need to put ourselves into the place within that allows us to find what is directly before our senses, hidden in plain view behind the cynicism of believing we already have the answers and know it all.

–From my book titled: Stay In The Magic – A Voyage Into The Beauty Of The Grand Canyon about our journey down the Colorado back in late 2010.