After two days of traveling to get ourselves into position, we are ready to launch onto this remote river called the Alsek. We are here with the kind permission of the Canadian government, as it is by permit that we are allowed to raft through Kluane National Park. Coming here is a rarity; less than 200 people a year opt for this adventure through such a rugged, pristine, and faraway place. Juneau is now 245 miles (397km) to the south and Anchorage 613 road miles (993km) to the northwest – we are way out there. Between us and the Pacific Ocean, there are no roads, shops, electricity, or flush toilets. We travel as a self-contained mini-armada. After a somewhat windy night, we woke for a quick cold breakfast and were underway as soon as camp could be packed up and stowed on our rafts. Caroline and I joined Bruce on his raft for this “first” day on the river.

It’s a bit gray out and chilly on the water, so we have all of our toasty rubber gear on that sits over waterproof pants that are on top of quick-dry pants that cover long underwear. The top halves of our bodies are layered in a similar arrangement, except Caroline and I also have hand-knitted hats to keep our heads warm. Over it all is the PFD, a personal flotation device, that we hope will not be tested for efficacy. Not requiring these extra layers or buoyancy protection was this female moose that strode right across the river but apparently was spooked by something on the shore in front of her. We first saw her from a good distance and immediately stopped paddling so as not to spook her. As we floated slowly downstream, the moose continued to inspect the right shore; whatever she was seeing, we could not. After the moose caught sight of us, she would shift her gaze from the shore to us, back to the shore, and then back at us. Finally, she called it quits and turned around to return to the left shore. Into the thicket, she strode; this would be the only moose we’d see on this journey.

About an hour downstream, we start getting our first hints of a blue sky. While sunshine may yet be on the itinerary, this is Alaska, and nearly any type of weather is possible; good thing we are prepared. This day on the river has similarities to our first day on the Colorado River down in the Grand Canyon. The scope and spectacle are too far beyond our sense of the familiar; it is impossible to relate this to anything previously known. I find myself unable to comprehend the magnitude. I may as well be a thousand days away from tomorrow because that might be the time required to give this some sense of understanding. It isn’t that I don’t recognize water, mountains, or sky; it is more the idea that there are no familiar landmarks ahead; there is only the potential for more of the incomprehensible. Oh, I’m sure some will fall right in and see this as just so much more of something similar to other experiences had previously, but this is my first time in the Yukon, and already, I’m aware that there is an infinity of detail surrounding us that I cannot stop to see. There are viewpoints in countless different locations under a billion different weather and light conditions that can offer a trillion different perspectives; the only position I will see this from is right here, right now, from my spot on this little inflatable raft. Insignificance screams out my name in silence.

I didn’t want to post another expansive mountain and river shot right away, especially one that is not all that great, but this one has a rainbow. Not just any rainbow either; this is the shortest, most ground-hugging rainbow Caroline or I have ever seen. It is also the second rainbow in two days. Caroline and I have likely been witness to well over 100 rainbows during our travels, shooting stars are another familiar theme. You can bet that we see these phenomena as notes from the universe that the proverbial wishes and pots of gold are easily found when one is out in the flow of nature.

The weather works hard here; it is like a chameleon that changes minute by minute. Due to the size of all that surrounds us, it is difficult to grasp distances, and is impossible to guess how far the horizon might stretch out before us. Our place down here on the water doesn’t help establish a good vantage point either; with heavy clouds obscuring what lies beyond the closest mountains, we are left wondering as to what we are missing. There’s this nagging thought that whatever has been missed these first two hours will probably forever remain unknown to Caroline and me. Even if we were to return in a year or two, would the river be able to be run, or might a glacier block our passage? Would the weather be harsh, rainy, or maybe snowy, with the view more limited than what we have experienced so far today? When we go to someplace like Disneyland, we can be nearly certain that we will have seen all there is to be seen, should we dedicate our efforts to do so. That cannot be said when visiting places such as Alaska, or the Grand Canyon for that matter. When trapped by the conveniences of highways, groomed roadsides, and finite city centers, our vision and imaginations stop at the boundary of these man-made environments. Out here the only limits are our ability to look deep, not just outside, but also within ourselves.

And then the sky opens to spill sweet sunlight upon all it reaches. Not even noon yet, and we are a million miles from where we were. The first mishap of the trip was a personal one for me. My brand new GoPro HD Hero2, which had not filmed a second of footage in its brief life, jumped overboard and died. I cannot confirm its death for certain; the body wasn’t able to be retrieved. It was attached to its suction cup device that will hold tight to objects that are traveling as fast as 150 miles per hour and was probably never tested on the rounded rubber front tube of an inflatable raft ripping along at five mph. Turning my back for a split second, the suction cup, the GoPro, a 64GB SD Card, and my brand spanking new LCD BacPac abandoned ship; taking close to $500 out of my pocket at the same time. You see, while the sky can clear and clouds will dissipate, the waters we are traveling are so full of silt that we cannot see a quarter-inch into the murk. There is so much silt that it sounds like the bottom of the raft is being sandpapered. Crispy crackles and pops rise from the raft’s floor. Uh-oh, and so is the water. We haven’t been through a single rapid yet, but I keep on bailing water that is collecting in the front of our raft. Do we have a leak? Might my camera be able to float up into it?

Adventure, glaciers, rapids, wilderness, and wild animals, we are here to see it all. Including the blossoming of wildflowers that spring forth to color a landscape that, for the majority of the year, is cold and hostile. It’s only mid-June, but within 90 days, winter will start showing its face, and the flowers will be long gone. Fortunately for Caroline and me, Bruce has been on this river seven other times and was able to make a pretty good guess when we might be able to see the wildflowers near or at their peak. His crystal ball worked well.

We stopped for lunch. Sandwiches, chips, fruit, and cookies are on the menu, standard river fare for a mid-day meal. After stuffing our gullets, it is announced that we are going to venture out on our first hike. I, instead, decline. I need to know the silence that exists here. I long for a moment of quiet that so far has not been found. If I could just sit here next to the shore, next to these beautiful wildflowers, I am certain I can find the tranquility that I cherish. The group trudges up the hill behind me; their voices fade, and I start to listen for the bear. There will be no bear finding a tasty man-morsel today; I am safe. Then, the quiet begins.

These rocks did not chatter; they did not groan under the weight of the earth that sits atop them, they sat motionless and quiet. I, too, sat still because if I didn’t, the synthetic clothes I require for survival here would create a racket to disturb the dead. The quieter it became, the more that silence demanded respect, I obliged. A slight breeze ruffles the nearby leaves; it must be a bear. Nope, it is just the wind reminding the trees that they know how to sing their own song. It had taken three days of traveling to find ourselves 10 miles downstream, but it felt like mere seconds before the marauding hikers crushed the quiet like an ant underfoot. I left a camera upstream from here; if someone should one day find it, please set it up on river left; really, anywhere will do, and find a method for connecting it to the internet. A webcam from this shore seems like a terrific idea to me.

There must be homes on the other side of that hill with a well-hidden road for commuters to get to and from work. How do people resist living in a place this gorgeous? I suppose 24-hour nights for a good part of winter with vast quantities of snow piled on everything, oh yeah, and the 500-mile drive to work all conspire to dissuade urbanization of these wildlands. That, and the insight of those bureaucrats, environmentalists, and left-wing fringe folk who think places like this are worth preserving. Not that its exploitation wasn’t considered, at least in part. As recently as 1993, there was a push to start mining copper further downstream. Studies suggested it would end in total disaster. Not only would it destroy swaths of pristine land, but it also threatened Dall sheep, wolves, wolverines, and the largest concentration of grizzly bears on earth. Author and boatman Michael P. Ghiglieri has written an excellent piece that goes into detail regarding this boondoggle; you can read it at the O.A.R.S. website by clicking here.

Meet Bruce Keller, our boatman. Want to know more about this great river guide? Read my book, Stay In The Magic! Shameless plugs belong on one’s own blog; it goes with the territory. As good as he is, he hasn’t stopped the water that is accumulating so fast that I have to bail out the raft every 20 minutes. Now I’m stumped, sitting here the night I’m writing this. I stare at the photo and think about everything I could tell you about Bruce, but there it is just a couple of lines above this one where I’ve said I won’t. Bet I can’t make it to the end of the telling of our Alsek adventure before breaking that devil’s bargain I’ve created. So, where to go with this? Oh yeah, sitting behind Bruce is John Hoffman, and next to him is Caroline Rhodes, the editor of my book titled, “Stay In The Magic – A Voyage Into The Beauty Of The Grand Canyon.” It is the book you are now getting pretty interested in and are considering purchasing!

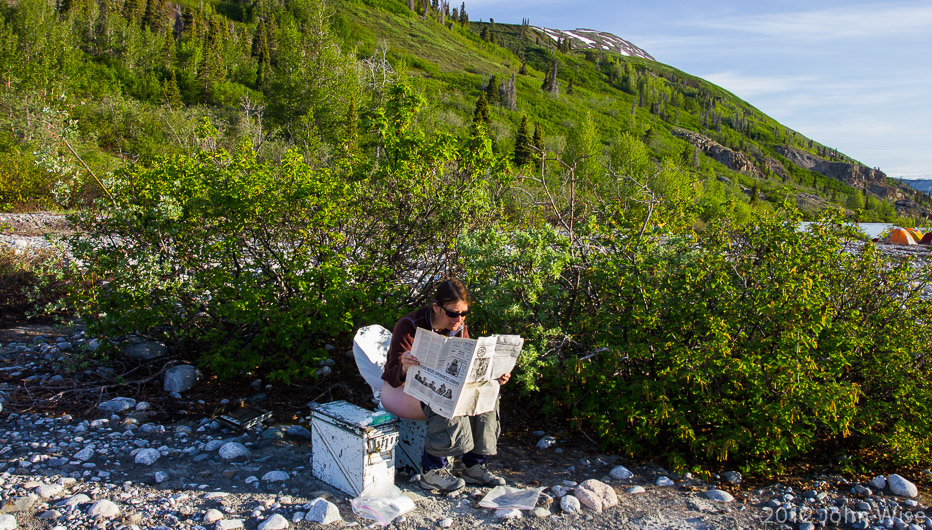

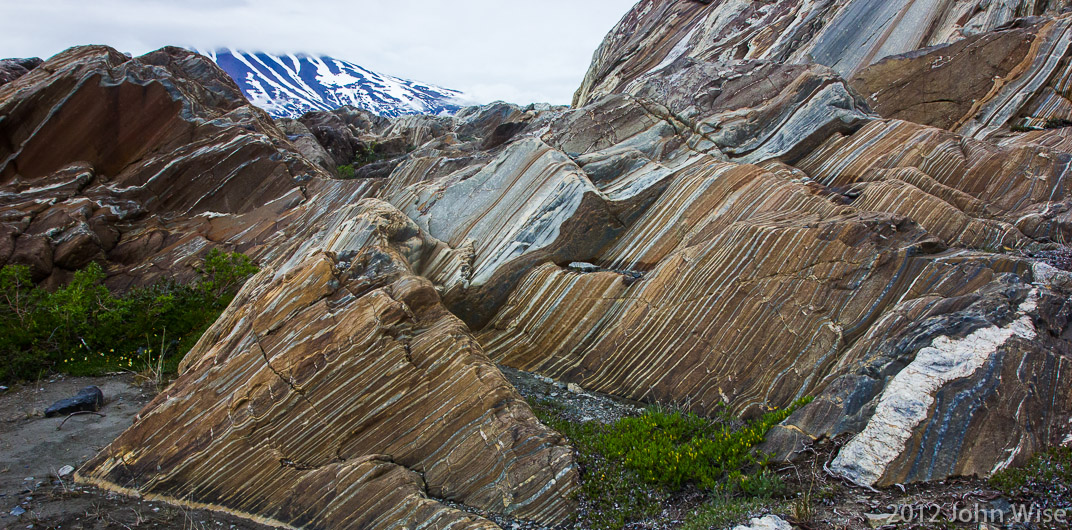

Would you believe these plants have started growing in the silty wet bottom of our raft? I didn’t think so. We are onshore. Camp is set up, and everyone except Bruce, Shaun, Caroline, and myself are about to go on a hike to explore a waterfall in our backyard; about a mile away. But before camp is nearly deserted, a call goes out to help empty, de-rig, and roll Bruce’s raft over. Right away, the culprit is identified: a big split in the rubber underbelly. How we didn’t go Titanic is beyond me, or maybe it was my steadfast bailing? Fixing a hole in a raft next to a swift-moving river turns out to be easy enough, except for the exotic glue concoction that should be bundled with a military-grade gas mask to protect yourself from the fragrant aroma of this toxic mix. Turns out that boatmen have all the tools they need for just such a job: beer. While sparing myself brain damage from the noxious fumes, I went exploring in our local vicinity; the picture above is a hint of what I found.

I have come to form a hypothesis regarding us ‘city’ people finding ourselves in the bigger world of immense nature. We do not truly know how to embrace a world without boundaries. It is as though we have been hit with a cudgel – relentlessly. With our wits bashed clean out of our heads, we lean towards the familiar; we wallow in the mundane. How have I come to this cynical conclusion, you might ask? Observation of our behaviors when transported into these vast, mind-expanding locations. For some people, this is manifested in the talk on the boats, where they are quick to drag their “interesting” lives onto the river for all of us to share in. For others, they are able to contain themselves until reaching the shore and the campfire before hell breaks loose; I do not want to know the smallest detail of what TV show these people find interesting – I AM SURROUNDED BY THE ASTONISHING SPECTACLE OF NATURE, and am very happy to be in the moment! Though I should admit, I, too, suffer from Mother Nature’s ability to overdose the senses. For me, I turn in. I look for silence; I try to find something to focus on that doesn’t bludgeon me with trying to comprehend the infinite. Already, just one day on the river, I’m losing my sense of place. So instead of joining the banality of regurgitating stories that can in no way compete with where we are, I try to slow down, to settle in. I laid down on the ground like a kid about to inspect the microscopic fauna and flora below his feet; I wanted to find intimacy with something more easily comprehensible.

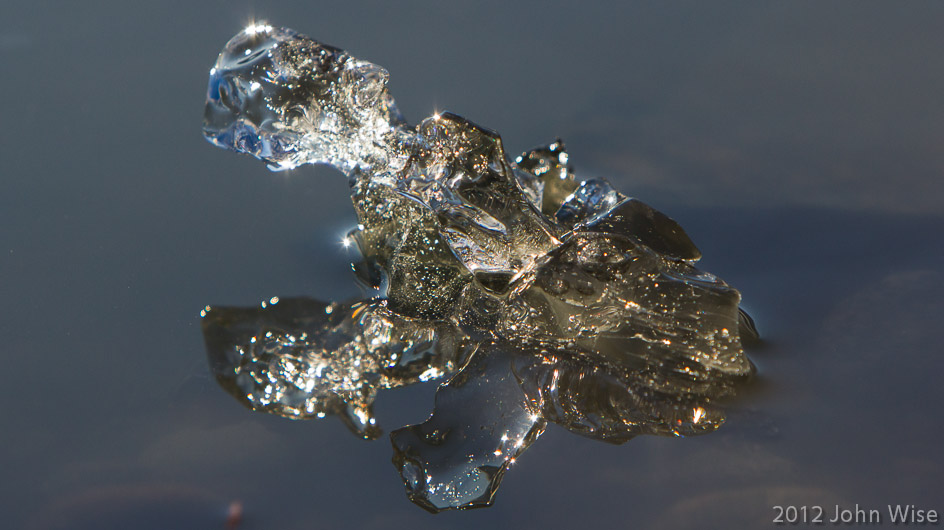

What I found was that the universe of the tiny can be more immense than that, which is obviously easier to see when looking at the sky and mountains. Down here on the ground, another universe exists. The soil is not flat and compressed; it is damp, dark, and teaming with life. Delicate crevices descend into dark shadows where my vision cannot penetrate. From out of those hidden places, nearly transparent insects unfamiliar to me crawl out and just as quickly dip into another hidden cranny. I look closer and find plants smaller than the head of a pin growing between grains of soil and sand. A spider scrambles over debris that has collected over the seasons; there is no telling how long the elements in this microcosm have played host to that and those who live here. Looking for something simpler, I am finding yet more big questions. What is the purpose of all of this spectacle? How does the life that exists here survive through the brutality of a long, dark winter where snow and ice are the rulers? What could that process of reawakening feel like if it were us waking from a long hibernation where our lives were suspended until conditions were once again fit for our springing forth?

I am certainly the one and only human being this bug will ever see in its lifetime. Its plain of existence does not require my presence; it is more likely that I am detrimental to its short life. Less than an inch long, there was something beautiful about this creature’s life and its place here about 500 feet from shore and the rest of the people I was traveling with. This bug has no limits on where it may roam; it doesn’t pay rent to be allowed to have a place on the surface of the earth to call home. It has learned to find food in its environment without needing to exchange labor for access to a meal. This turquoise-suited explorer is able to scale blades of grass a dozen times taller than its length, where it can observe the alien-human who has barged into its universe. Both of us sit still, not flinching, me imperceptibly breathing, it practicing simple diffusion. So, who or what is freer? I’ll have to go home; I couldn’t survive here a winter on my own, while the grasshopper is home. It and its kind will survive – if “we” let it.

There is too much to see here. Instead of finding the familiar or at least the comprehensible, I am no more certain of my surroundings than I was when I came over to this small patch of tranquility. I will remain lost in the fog of vastitude here at Lava Creek Camp and remember how this first day on the river is only but a smaller part of a tiny part. We are but a small element in the larger world that resides in a universe where many of us can seemingly only survive by focusing our attention on those things we already know, lest we become lost in the magnitude of possibility where our minds may not have the elasticity to grasp the totality that bombards our senses. At least I will contemplate these things and continue to try to find meaning when stripped of the familiar and my everyday routine.