The past couple of weeks I was offered the opportunity to beta test a new firmware for the Stillson Hammer MKII from Industrial Music Electronics. The Stillson Hammer is a Eurorack format modular synthesizer piece of gear from Scott Jaeger out of the state of Washington.

I first learned of this device in the late spring of 2016, and by the summer, I was ready to place my order. The Stillson Hammer had a rocky start when it first shipped in March 2016, with more than a few bug reports and frustration getting it to play nice. By the time I made my order in July, the firmware had been updated to version 1.5, but it was still less than perfect. Hot on its heels was firmware version 1.666, which was poetically appropriate, seeing that the list price of the Stillson Hammer was $666.

Even with its share of wonky behaviors, this sequencer was building a dedicated fan base. In mid-September, I finally received notice that my unit was shipping; my enthusiasm had not been tarnished by the negative reports. I guess my many years of testing software braced me for dealing with a product that is evolving.

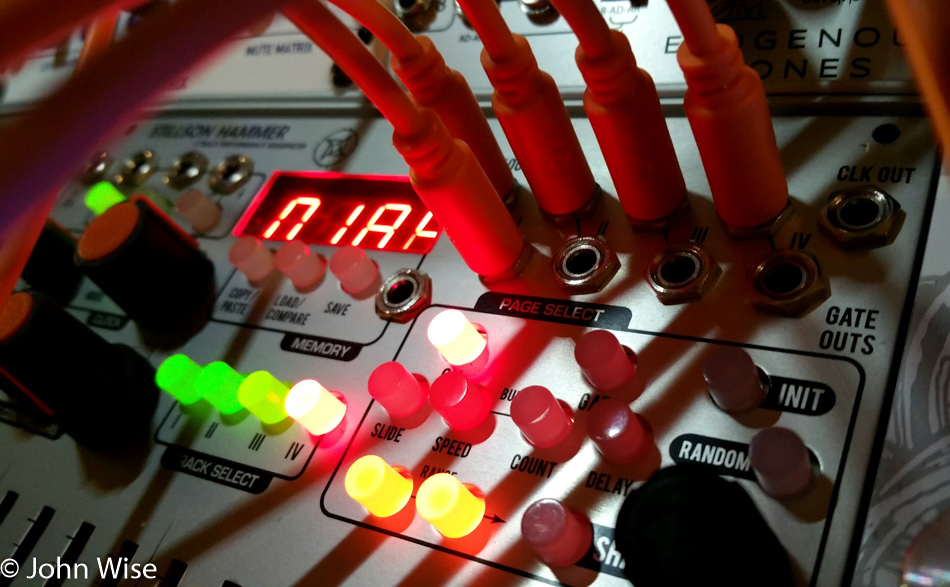

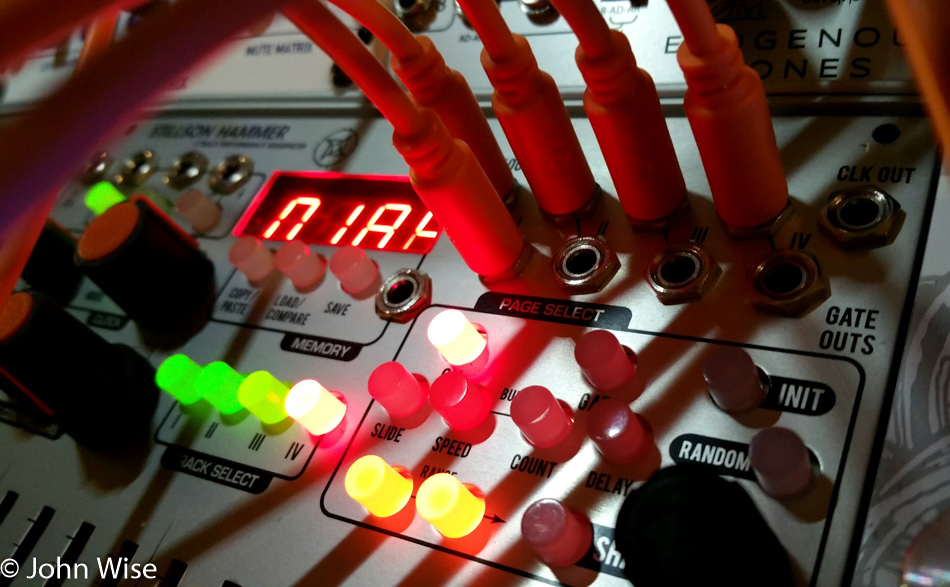

What made the Stillson Hammer so desirable was its emphasis on live performance and modulation possibilities. While the MakeNoise Rene was arguably more popular that summer, it wasn’t suited for live shows. The other big point of differentiation was that this sequencer had four CV and four gate outputs. In addition to the 16 sliders for snappy adjustments of gate and CV values for each of the steps per track, it appeared that we were on the verge of a huge shift in sequencers for the modular market.

The ER-101 from Orthogonal Devices may have been more fully packed with features, and it was certainly out a lot longer than any of the competition, having been released in December 2013. The companion device known as the ER-102 followed a year later, but with the full system price at over $1000, it was out of reach for many. What it had going for it was deep programmability, four tracks, 99 steps, eight CVs, and four gates; with the ER-102, the capabilities skyrocketed. While this module remains a strong contender as the best sequencer for serious composers, it is a bit difficult to program on the fly during live performances. Colin Benders is certainly the exception to the rule regarding this last claim.

So, creating something that went beyond the one track, one CV, and one gate-dominant design that could be had for only $566 on sale was something the market was hungry for. Scott Jaeger hit on the right design at the right time. Keeping an impatient fan base happy while he nearly single-handedly dealt with the pressures of manufacturing, creating new products for the next big trade shows, maintaining existing products, dealing with customer service, and having a life may prove as difficult for him as it does for the majority of small companies operating with between 1 and 5 employees.

When my Stillson Hammer arrived, it may not have been perfect, but I was even less so. This was my first dedicated Eurorack sequencer, and I honestly didn’t understand the first thing about tracks, steps, gates, scales, ratchets, delays, and transposing. As I stumbled through some rudimentary tutorials in exploring this thing of complexity, I had plenty of other options within my rack to distract me from the other things I didn’t understand.

Around the same time all of this was happening, I was expanding my company that had just gone public and was taking my employee count from 20 to 30 people after raising another round of capital. I was busy. As the end of the year rolled around, I was mostly oblivious and unaffected by the issues I was reading about the Stillson Hammer in the forums, as the topics were mostly beyond my comprehension and fully in the domain of people who apparently knew what they were doing. I’ve since come to learn there are a lot of people new to Eurorack who also have no idea what they are doing.

January 2017 saw a lot of chatter about pending firmware updates. I took the opportunity to order a Picket 3 device for $20, so I’d be ready when it arrived. In April, firmware version 1.777 was delivered along with my skill set having to come to grips with updating my Stillson Hammer.

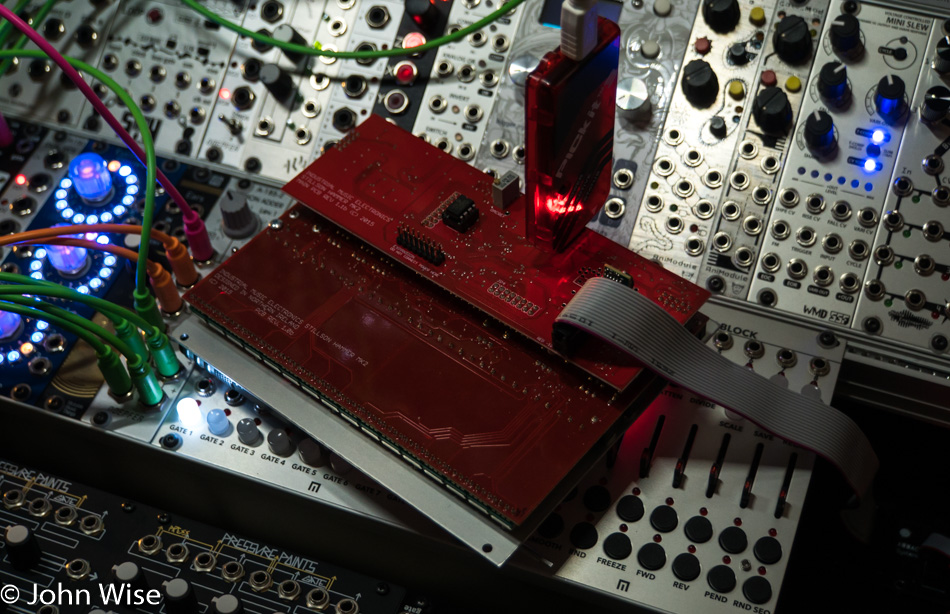

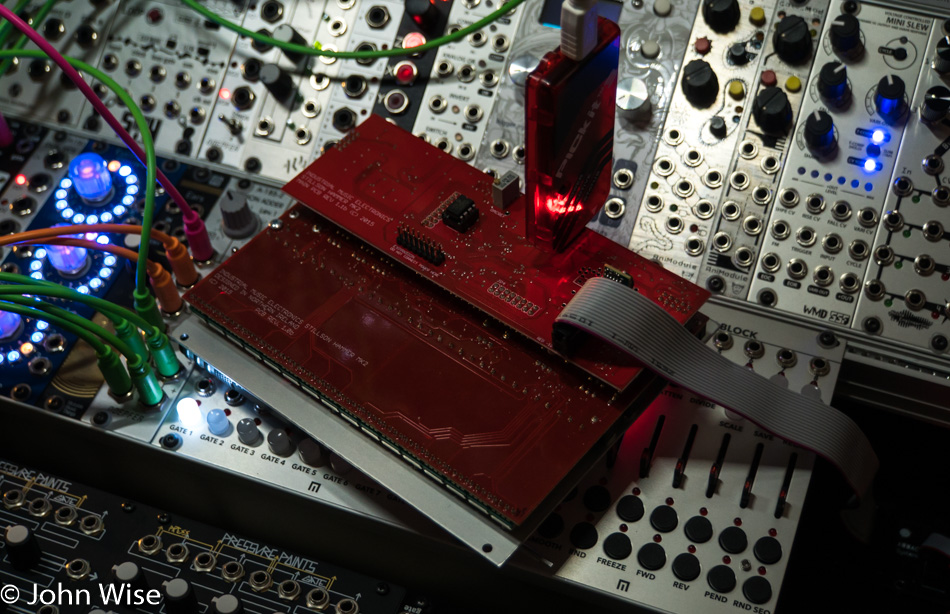

To someone already lost in the confusion of this modular synthesis entanglement of complexity, it is easy to feel updating your device is a near impossibility. First, I needed this strange little red electronic device known as a Pickit that I’d never used before. Next, I needed an application called MPLab IPE, that’s a 600MB download and, at first glance, is intimidating. The Stillson Hammer user manual offered nothing in the way of help. Fortunately, some friendly soul on the internet shared his story about how to update the firmware.

Still being a green user of sequencers the advances from 1.666 to 1.777 were invisible to me. Then, in September, Scott started releasing a quick succession of updates, starting with 1.85 and culminating with 1.852. By this time, I had cultivated enough familiarity with the Stillson Hammer that the improvements earned quality of life points for me.

Just a month later, Scott reached out to me after he and I exchanged a couple of emails regarding an order I had made for a Plexiglas window replacement for the red film that shipped with early units. He asked if I’d be interested in testing firmware 2.0. My answer was an enthusiastic yes.

How Scott thought I’d be a good candidate to test his firmware is beyond me, but as I accepted, I was determined that I was going to give him some kind of feedback.

What was great about the next few weeks was that I had to methodically go through every single detail that I could explore to the best of my ability. My familiarity with the Stillson Hammer was going up exponentially. The previous year spent learning about the multitude of other things I needed to understand was starting to pay dividends in my overall understanding.

There were a lot of rough spots and inconsistencies still in the firmware prior to this push for 2.0. There were probably many things I reported to Scott that were not issues but design choices for things I wasn’t familiar with enough to understand why they worked the way they did. All the same, Scott took the time to read each of my short missives and, on occasion, explain why something was the way it was. As I progressed from beta 1 to 2, 3, 4, and finally released candidate 1, I saw more than a few things I’ve reported fixed and at least a couple of new additions. The capability and maturity of the Stillson Hammer is now rock solid, in my humble opinion. With the new firmware, it will be an interesting next couple of weeks as others start to dissect and push the boundaries of what this sequencer does; I hope to learn a lot more from these enthusiasts.

Through all of this, the tutorials from Robotopsy and a Japanese language tutorial from Clock Face Modular were watched more than a couple of times each. The user manual in its first incarnation didn’t help me that much, but it promises to get better with the final release of the 2.0 firmware. Giving yourself some dedicated time to methodically dig into a sequencer while reading and watching all that you can ultimately pay off, but it’s a tough slog when you come from knowing nothing about music composition prior to diving into the world of Eurorack.