Snow and glaciers are part of a gorgeous start to a day on the Alsek River, well, that and a hot breakfast.

We won’t be in camp much longer as it’s almost time to get out on the river.

The mountains in the background are part of the Noisy Range. The sky is a mixed bag of shifting clouds that is, on occasion letting bits of sunshine speckle the landscape.

Straight out, far in the distance between these two mountain ranges, lies the Pacific, and fortunately for us, that’s not the way we’ll be traveling today. For one, no river runs out that way, but if there was, it would mean we are almost finished with this journey. We are now entering the confluence of the Tatshenshini and Alsek Rivers. While this is just one small braid joining us, soon we’ll be on the full flow of the combined rivers.

Another hanging glacier falls out of the mountains alongside the merging Tatshenshini and Alsek Rivers in British Columbia, Canada.

This photo was taken in the middle of the now merged Tatshenshini and Alsek Rivers which at times feel more like a lake.

One minute, I’m looking behind us, and the river reflects the golden light of the early morning sun, and then a minute later, we are looking at winter.

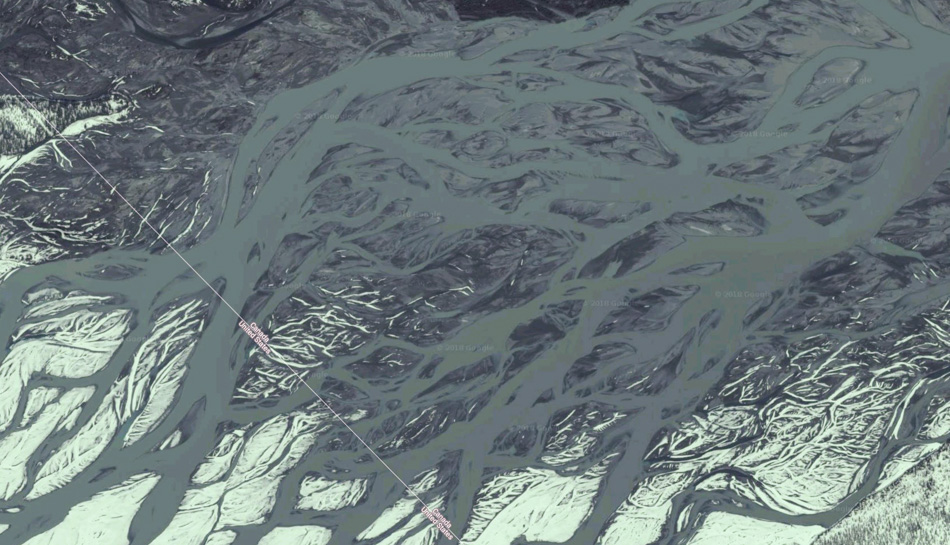

Here’s where things start getting a little more difficult because the Alsek is about to become a thousand shallow braids, and our trip leader, Bruce Keller, has to make some serious decisions based on his years of studying rivers. This labyrinth demands we engage in a zig-zag hunt for the path that will take us to End Glacier, which is just ahead on the left. While that spot down there in the United States might look relatively close (we estimate it to be between 6 and 7 miles from our current vantage point), we have about 15 miles of rowing ahead of us due to the course we will have to take.

We are sitting in that mess of braids, as seen in this satellite image I found on Google Maps. It was taken in winter when flows are low and much of the river in its thinnest parts is frozen, at least on its top layer. On the day we were running the river, the entire channel may have looked much like a lake, but in some places, the water would be only inches deep.

There may have been water flowing over this gravel and sand bed some weeks ago, but now it’s an exposed bank that we are floating past. To my untrained eye, the water was going in all directions at once. While this river could be said to be flowing through a river bed, that path is changing all the time from day to day and week to week. In eddies, it runs back upstream; near gravel beds, it can run sideways until it spills back into the main channel. Water that is being dragged out of the main channel is called a bleeder and where water has accumulated and starts reentering a larger channel, that is known as a feeder. Earlier in my blog post, I spoke about how people on these rafts do not want to step in the water to help dislodge a raft that has run aground; this image is a perfect example of what might lay just below the surface and getting a foot wedged between half-buried trees in fast-moving cold water is not somewhere anyone wants to attempt a rescue.

Back in Canada, we had ice and rocks and a couple of flowers; here in the United States of America, we have lush mountainsides and flowers in abundance because America. I’m just kidding, of course, as this has been a large part of the landscape ever since we arrived on this side of the Tweedsmuir Glacier.

Around the bend from End Glacier, we get our first glimpse of Walker Glacier, thusly named because it used to be accessible. The name of Walker may no longer be appropriate, though, because it has been retreating since 1984 and the section our group hiked on five years earlier has collapsed and helped create an even larger lake in front of the shrinking glacier.

Where Caroline and I set up our tent next to the river was the face of Walker Glacier thirty-three years ago. Back in the mid-1970s, when Bart Henderson was out exploring the Tatshenshini before setting up the first commercial white water runs in this area, he must have encountered a very different environment. Back then, in this region, the mountains were perpetually snowcapped, and the glaciers extended hundreds of feet further than they do now. One has to wonder if someone traveling through thirty years from now on an October run will only hear stories of glaciers that used to be in the mountains and that people were even able to walk on them shortly after getting off their raft.

On our way for a closer look.

There will be no walking out on that jagged mess of potential death, but it sure is pretty.

Rocks floating in the water waiting to be released from the ice that for thousands of years have carried them to this point. Sometime soon, the ice will have melted and will be on its way to the Pacific, and the rocks will find their way to the bottom of the lake. This is another example of how erratics are brought to new locations.

Like a couple of erratics, these two from somewhere else keep ending up in places they are not originally from. Notice Caroline’s beanie from Yakutat Coastal Airlines? She got that one five years after her first “bush plane” ride. My beanie was handmade by Caroline, and has since been to Yellowstone for some snowshoeing, to Oregon on the coast during winter, and twice now to the Alsek.

As we explore the lakeshore next to Walker Glacier I’m struck by the idea that no one else on Earth could be having the experience I am right now. While in the city back home, my office, or the grocery store, we all experience a shared reality. Out here, there is ample opportunity for 14 people to have a distinct perspective of a view that only they will hear and see. And while any two people looking at, let’s say, the Statue of Liberty will have distinct but similar experiences, they are relatively the same as the Statue is unchanging, and the environment, aside from the weather, will be relatively constant. On the other hand, there are experiences like today’s that are dynamic and will be mostly different from anyone who follows. I think this fluid state of change is what draws many people into these types of experiences, such as when a surfer finds a wave only for it to dissipate, never to be ridden again, allowing it to enter a kind of mythological status. Are these kinds of journeys our way of joining the mythological narrative that surrounds our existence?

These moments of unique experiences well removed from our routines beg a question for me: is there a hierarchy of greater or lesser impact on the character of the individual from the grade of experience that affects us on a deeper intrinsic level? If so, how do they broaden or narrow one’s focus or affinity for what life is offering? Is our relationship to the nature found in these extraordinary locations extended and made more secure, or was our DNA and previous experiences already taking us down this path?

The waters of the Alsek River and the lake that has formed at the Walker Glacier are joining here, where even the patterns in the mud are strikingly beautiful to me.

One can easily get tired on vacation and in need of pulling up a spot in the sand to just lay down and get a little nap.

It’s 9:00 p.m. as I head to the river to check the lighting and make sure nobody has made off with one of our rafts.

The sun has come out to smile upon us here in Alaska as our day unwinds.

A few of us are up late on a clear, cool night. While the roar of 14 voices can sound cacophonous in this kind of landscape, the river seems to have slowed down in reverence to the moon and delicate light that is defining our night and is somehow quieter than it was when we landed. These moments late in a river trip are when one wishes to roll back the clock to when we were first launching and make it a point to keep sleepiness at bay so we could enjoy many of the nights where the midnight moon silently crawled across the sky while the rest of our travel companions slept warm and soundly over in their tents.