So, we arrived in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico, last night but I’ve not explained why we are here. Almost exactly a year ago, I reached out to Norma Schafer via her Oaxaca Cultural Navigator website, asking about tours she has on offer that take travelers into the world of indigenous Mexican textiles. Sadly, her Chiapas tour for February 2022 was already sold out, but she did inform me that due to strong interest, she was considering adding a second trip. We were on the waiting list. A month later, I received an email notifying a number of people that she was opening that second trip that would begin on March 8, 2022. We sent in our deposit.

From Norma’s website, she described the trip as, “My aim is to give you an unparalleled and in-depth travel experience to participate and delve deeply into indigenous culture, folk art, and celebrations.” All of this centers around the textiles and artists who are keeping these ancient crafts alive into the 21st century. That’s why we are down here 2,300 miles south of San Diego, California, and just 90 miles from the Guatemalan border. We are entering the world of the Maya.

Breakfast starts the day just off the courtyard of our lodging here in San Cris, as it’s affectionately referred to. During this first meal of the day, we met the other ten people who were part of our group: the translator and presenter Gabriela Yasmin Fuentes, and trip organizer, Norma Schafer. Gabriela was on presentation duties, introducing historical background information about the structure of Mayan society and the clothes of pre-Hispanic cultures in the region.

This was also the first moment the subject of authenticity versus inauthenticity through the lens of colonialism is brought up, and what our expectations might be regarding potential biases about how we may want to have the people we are going to meet fit in an ideal box of our own mythologies that is not congruent with reality. It’s emphasized that change is at work down here, just as it is in the various corners of America we just arrived from.

After a short pause to finish getting ready for the day, we ventured up the road on our way to the Centro de Textiles del Mundo Maya.

Along the way, we get our first glimpse of the layout of San Cristóbal and have to appreciate the weather as we are promised rain at any time.

Streets are narrow, buildings old, sidewalks almost non-existent in their narrowness, and curbs that can break ankles from their towering heights if you are not careful. When I took this photo, it was because of the architecture; only later did I realize that this is a Burger King, and no, we never ate there.

We’ve arrived at the beautiful old Santo Domingo Church (Iglesia de Santo Domingo de Guzmán) with its baroque facade from the 17th century. The attached ex-convent building is where today the textile museum and Centro de Textiles del Mundo Maya are housed. Unfortunately, the church is temporarily closed; we saw workers repairing the roof damaged in the 2017 earthquake. The Santo Domingo Market, with its busy stalls, surrounds the church and museum.

The beautifully restored courtyard of the convent.

Today is our lucky day as the ladies were able to book us a behind-the-scenes tour of the restoration area and classrooms that the administration of the museum is actively trying their best to fund in an environment where raising money is no easy task.

Maybe the only way to bring about the attitudinal change required to take greater pride in the cultural heritage of a people is to foster that concern among children. Get them involved with art and teach them where this history comes from and the importance of maintaining the skills of their mothers and grandmothers lest they are quickly extinguished. Someday, if those who could have been teachers have all passed, there will be no heritage rising out of the past, and those things that lend character beyond a bland global media-driven domination will sink into obscurity.

But aren’t these your own bourgeois pollyannaish and likely unrealistic wishes, John? Cynicism says yes, and maybe my older age too, but just as Greta Thunberg inspired a vast swath of young people to consider their future in which survival can no longer be certain, I can hope for someone else to find the force of a voice that will be able to move a generation away from cultural oblivion brought on by conformist banality and face these extinction events with the vigor previous generations lacked the strength for.

This is Gabriela, and while I can apologize to her for posting this masked, almost anonymous photo, Caroline loves her shirt, so I’m including this as a reminder to my wife of what it looked like.

This is a rolled-up backstrap loom and is the tool for how most everything in this area stretching down to Guatemala gets woven. Every article of indigenous clothing you see here today was created on one of these, and I’ll include a better image of one further below.

Meet Alejandra Mora Velasco, the director of the textile side of the museum and a very impassioned woman trying her best to represent the inclusion of cultures regarding all the people of this southern region of Mexico and build a world-class museum that can play a key role in cultural preservation while safeguarding these tiny pieces of history at risk of disappearance.

Culture, artifacts, and knowledge of our society tie us to our past and allow us to create futures that hold a semblance of familiarity. Here in Mexico at this time, art and the customs that are represented in museums are not viewed so much as treasures but as places that attract the bourgeoisie while the needs of the proletariat remain neglected. So, funding for the museum from the state or federal government is mostly neglected as they have more pressing issues to deal with, such as migration from the south or the tensions created by people leaving Mexico for the United States, inflaming a large part of the U.S. population.

In the background are chickadee grass and moss, which are just two of the plant materials used as natural dyes for coloring fiber, an important part of making handcrafted textiles.

Some of the pieces in the collection are no longer in perfect condition as they had been used for their utility and were not part of some wealthy aristocrat able to maintain things to a high order. Between 1972 and 1979, the anthropologist Francesco Pellizzi collected 793 textiles, and with the help of American cultural preservationist Walter F. “Chip” Morris Jr., a trust was set up to protect these important works of the Chiapas region.

After our behind-the-scenes tour, we entered the main gallery of the collection, where we were introduced to master weaver Eustaquia (not 100% sure of that name), who was on hand to answer questions. Not being a fiber/textile artist myself, I was more interested in photographing all the beautiful things than asking questions.

The cosmic flow moves through Mayan garments as they play an important role in tribal and personal identity. The tunic on the left is of Lacandon origin, representing the sun, moon, and stars. Lacandon is located in the deep jungle near the Guatemalan border and these traditional tunics were made out of pounded bark or papel amate. The ceremonial huipil on the right looks like it is from Magdalena Aldama. Merriam-Webster defines a huipil as – a straight slipover one-piece garment that is made by folding a rectangle of material end to end, sewing up the straight sides but leaving openings near the folded top for the arms, and cutting a slit or a square in the center of the fold to furnish an opening for the head, is often decorated with embroidery and is worn as a blouse or dress.

Little did I know on this first day that we’d soon meet the woman who created this impressive huipil. This is a wedding huipil from Zinacantan, the only place to incorporate feathers and rabbit fur, thanks to a historic link to the Aztec empire. It looks as if this particular huipil utilizes threads dyed with natural dyes.

Sure, a part of me wants to share details about these textiles that I might have scooped up from placards that may have accompanied the pieces, but I didn’t photograph those, and that’s if they even existed, a detail I overlooked. You see, if I had been wandering the landscape of this region 50 years ago with the sole intention of experiencing what was to be seen and I wasn’t an anthropologist or a cultural preservationist, which I’m obviously not, I would have been content to just take it all in.

So I’m simply moving through the exhibit and accepting at face value that these textiles are representative of the people in this corner of Mexico. Maybe as the days play out we’ll learn more of the motifs when we are visiting the villages noted in our itinerary.

Not an expert yet but I do know that this, too, is a huipil and that the colorful work that adorns the backstrap woven fabric is embroidered.

The panels that come off backstrap looms can be used for various things, such as shawls, bags, blouses, skirts, wedding dresses, men’s clothes, ponchos, and likely other things I’m not coming up with as I write this.

Because backstrap looms are only so wide, the fabric is woven in panels and then stitched together. Look closely, and you’ll see the stitches right down the middle. In this case, the weaver was able to “hide” the seam; in many cases, the seams are embraced and adorned with colorful randa embroidery patterns.

The seam is obviously much easier to see in this piece.

I’m thinking I should just remove this image as I have nothing to say about it but removing a single photo just doesn’t seem that it’ll make all that big an impact on this idea that I write to each photo I post.

Yep, I’d wear this one.

Might be nice if I can challenge Caroline to find us a chart to decipher Mayan imagery in textiles so we could share some of the meaning found in these clothes. This huipil is woven in the Pantelho style. The motifs are added during the weaving process with supplementary wefts.

Our tour of the museum is coming to an end; time for some shopping.

We are in an old chapel, which is now the museum shop called Sna Jolobil. The name means “The House of the Weaver,” and they are operating as a cooperative of more than 800 members from 30 different indigenous communities. In terms of quality, everything in this store is top-notch.

While this was the first piece I saw that I liked, Caroline had different ideas.

She spotted this “Blusa” (blouse) and felt the color better suited her, so this will stand in Caroline’s history as the first article of regional handmade clothing she purchased here in the Chiapas town of San Cristóbal. It is made with linen fabric, something she loves to wear, and was quickly followed by a similar blusa of white cotton with more colorful embroidery.

For the next 30 minutes, we’ll be wandering around the open-air Santo Domingo Market in front of the museum.

We’ve not even been in San Cris for 24 hours yet, and I’m skeptical of buying clothes in the open market after seeing the quality in Sna Jolobil. How can one tell what’s handmade and what’s factory-made? I’m sure good weavers can tell the difference, but I’m a bit naive; I’d guess that the cheaper stuff is, the poorer the quality and the likelihood that it wasn’t handwoven or hand-embroidered.

Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de Caridad (Church of Our Lady of Charity) is nearly hidden by the market.

Something interesting, nearly profound, is occurring to me as we have now spent some days in Mexico City and are walking around San Cris: children as young as two and three here and maybe about six in Mexico City are allowed a free range of play but the really amazing aspect is the lack of whining from children wanting attention, not wanting to do something, or just being loud and obnoxious as they learn from their parents that’s not the way the world works. When we do see mothers with their children, they are not anxious or threatening towards those kids; they are quite calm and are not using high-pitched cooing baby voices. I wish I could find some insight into why so many mothers in the United States use the approach of hysterics, snapping, threats, infantile speech, and intimidation. The funny thing about the situation here in the state of Chiapas is that the average person only has about 6.5 years of education compared to the average American with 12.

There’s no way we’ll see each vendor selling things in this market as it’s dense, super dense. Our 30 minutes of racing around the place are almost over.

Growing older and cynical is a bit of a curse. Thirty years ago, I might have been compelled to buy one of everything for sale here to add to our collection of knick-knacks that remind us of where we’ve been, but now all I see is cheap junk that doesn’t really reflect much of anything in the culture. Instead, it’s programmatic stuff designed to appeal to certain aesthetic sensibilities of tourists who find a kind of authenticity in the place they’re visiting due to certain motifs that hint at particular icons and symbols people want to believe embody the character of the environment and local population. Silly old man.

Oh, that one looks nice.

Nice enough to buy, sold to the German woman. The fabric with the woven-in motifs is from Venustiano Carranza, but the “rococo” embroidery on the yoke and sleeves was added in Amatenango. As we will see over and over, each municipality or region has specialized motifs and techniques that are quite recognizable.

Lunch was had at a hybrid coop of fiber store and restaurant called Belil Sabores de Chiapas Restaurante. Our meal was included as part of our program and included local flavors to make things easy we had been given entree choices ahead of time. We started with a glass of guanabana juice, which in the U.S. is known as soursop of the custard apple family. Next up was a bowl of green soup that I couldn’t get the specifics on, followed by our entrees. Mine was the chicken mole, and Caroline had vegetarian chalupas with beets, along with plantain, bean, and cheese croquettes.

Our host, Norma, roused a nearby business owner, Benjamin, at his shop called Casa Textile, who opened up for our group. After introducing himself and explaining his work of bringing women a venue to sell their wares both from his shop but also increasingly on the internet, he told of some of the cultural difficulties and the changing landscape of meeting fashion demands not only in Mexico but for people outside the country too. The pieces shown in the photo above are still backstrap woven but use rayon threads, which introduce a lovely shine and drape, allowing marketing to customers who may not be interested in “folksy” attire.

Telling us that nearly everything was for sale in his shop, Caroline surprised Benjamin with her request to purchase a backstrap weaving sword. Seemingly perplexed but maybe impressed too that a weaving tool from Guatemala would be that meaningful for her, he told Caroline to just take it; for free!

— Note: the sword made it intact back into America through customs without issue.

Before leaving Casa Textile, we tipped Benjamin for his gift, and Caroline bought a red, white, and black Pantelho cowl. This dressed backstrap weaving loom hangs at the entrance of the shop.

The day is not quite over as we make our way back across town to another shop featuring woven textiles from the area.

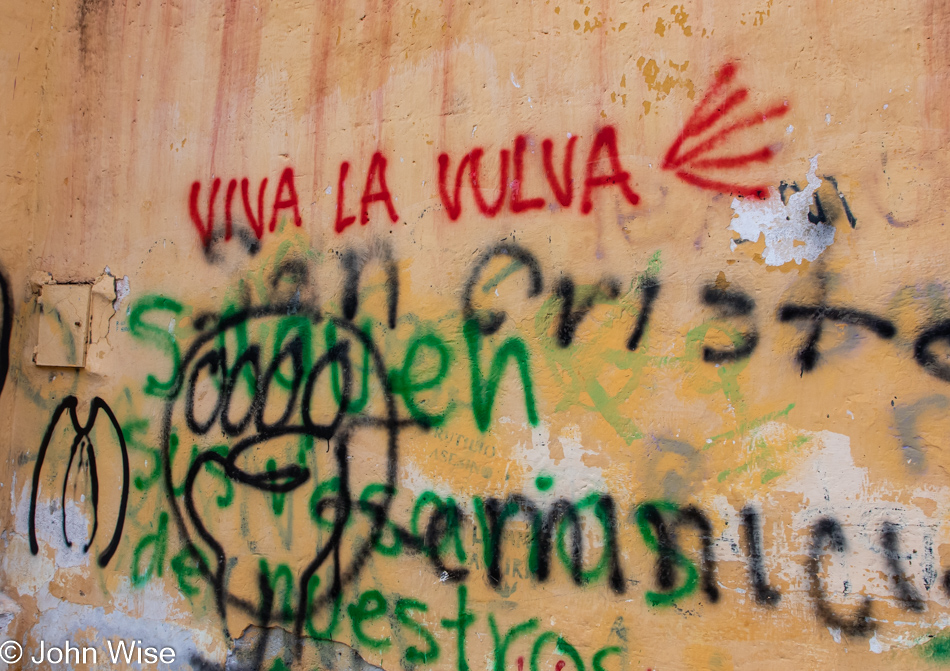

If you noticed some of the details on yesterday’s first photo in the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, the inference was me giving a nod to International Women’s Day there on March 8th. Well, this graffiti Viva La Vulva, meaning Long Live The Vulva, could be considered a reference to that statue in the photo; maybe you should have a second look.

I want this little shopping mall called Esquina San Agustín in Phoenix and have to ask, why can’t we have such nice things?

An alcohol-free mojito topped with coffee from Amor Negro Café. I should point out that we were not here to admire the architecture, design, or coffee concoctions (although Caroline and I shared a cup of simple Americano because, at this point of the day, a little energy boost was needed) but were visiting El Camino de Los Altos a coop store that features more high-end textiles. I might have featured a photo of their shop, but the lady working there was adamant that no photos were allowed. There is also a Carmen Rion store here, which features a high fashion and modern take with the occasional indigenous or traditional influence.

Caroline and I had dinner at Casa Lum restaurant, a recommendation by Norma. The food was excellent. I had lechon (suckling pig), and Caroline had a shrimp dish, but in retrospect, it didn’t really matter because food is currently playing second fiddle to the cultural immersion that is saturating our senses. Tomorrow, we will head out on our first road trip into the countryside, and I have no idea what to expect; what a great place to be.