It’s 5:00 a.m., and the combination of full bladder and restlessness jostle me awake. The crew introduces me to a sound that will become all too familiar in the coming days: the metallic whoosh of pressurized propane, firing the stove that heats the water for our coffee. I give in to the idea of waking and would happily step outside, but I’m finding the pull tab of my sleeping bag stuck, requiring minutes of mummy-like wrestling with a zipper that only wants to eat more bag. Cursing my predicament, I would rather be outside emptying the little blue bucket we had picked up last night to ease the pressure of the bladder, but I’m a prisoner right now. One and all, we were encouraged to place a bucket next to our tents before retiring for the evening. In the past, trips to the river at midnight while half-asleep have resulted in passengers taking a fall or a swim, later to be found sleeping in the sand or floating downstream, and not in a good way. Finally, having escaped my entrapment, I deliver our bucket to the river for emptying and rinsing before finding relief for myself. Maybe two buckets last night would have been in order.

Back at the tent, I help Caroline pack our waterproof sacks, called “dry bags,” trying to get an early start. We are still unfamiliar with the process of getting organized on a river and don’t want to be laggards. The dark blue-gray twilight will soon give way to the pastel blues and pinks that accompany the rising desert sun. The call for coffee goes out, but we focus on pulling down our tent and dragging bags riverside so they may gain passage aboard the rafts that accompany the dories.

First call for breakfast. Boxed milk and dry cereal is what I was expecting, but that isn’t on the menu today – well, it is if one really wants it. The hot choice is apple banana pancakes, butter, warmed real maple syrup, bacon, and fresh sliced cantaloupe. A loud pronouncement of “First light!” breaks through the morning quiet. It is customary in the Canyon for the person who sees the first golden rays of sunlight falling on the rim above to make the announcement that first light has been seen. We have now learned how First Light Frank earned his nickname. Frank’s official title is Swamper; this is an unpaid position for a couple of lucky individuals who are along to help the boatmen in exchange for free passage on one of the supply rafts. More than half an hour passes between eating breakfast, washing our dishes, and getting lost in our first ever sunrise on the Colorado within the Grand Canyon. Where did the time go?

The call of nature and my body are moving towards synchronicity, with an apparent intent to cooperate. While it shouldn’t, or wouldn’t, normally show up in a book, this movement is not like that of normal times. This reference must surely be categorized as too much information, but the coffee and breakfast bring on that old familiar downward pressure, signaling me that I’m about to have my first encounter with the Unit. The luck of it all is that the key sits alone, allowing me to head directly to La Pooperia. Up and over hill and sand dune, this moment of exercise adds urgency, blotting out any idea of considering what must happen next. Snap, zip, up with the lid, and hello river view. Now, while the Unit is a good distance from camp and offers great privacy from your fellow passengers, it will remain set in plain view of the bigger world for the duration of this trip, with a startlingly clear window of everything else but camp. Settled in, comfortable, and content with the ease with which I adapt to what yesterday seemed awkward, I take up my best imitation of Rodin’s famous statue, the Thinker, and quickly begin to think too much. What if another boat trip was floating downstream right now? Would I clamp down on the plumbing and try to slink away unseen through the grasses? Or would I put on a big happy smile and wave enthusiastically? No need to test my fight-or-flight response, and without crisis or issue, my business is done, and the key is handed off to the next person now in line. I wash my hands.

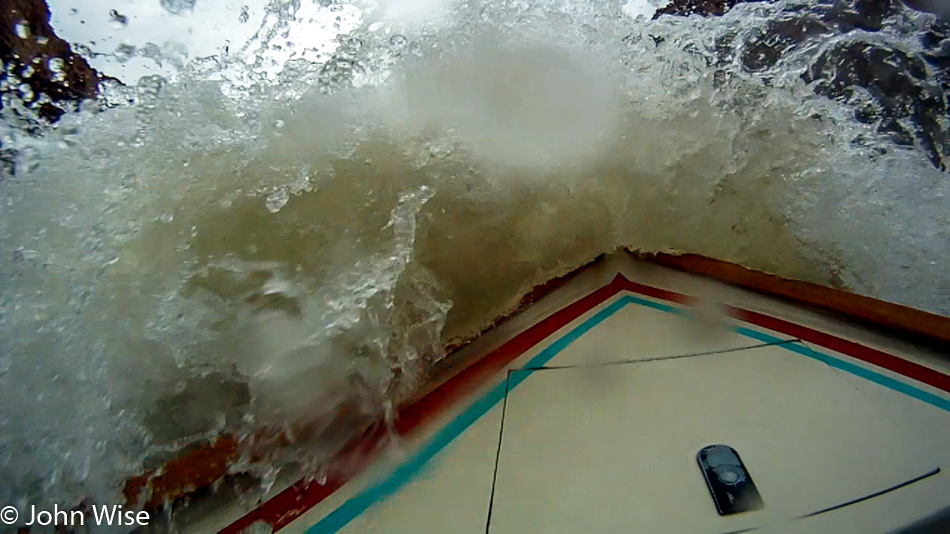

In quick order, rafts are packed and bags tied down, the kitchen is stowed, last call for the toilet before it’s resealed and dropped on a raft. If you are not in your waterproof gear, you should soon get that way – Rondo promises us a Big Rapid Day. Just before 9:00 a.m. Caroline and I push off on the One Eyed Jack with Bruce at the oars. We are the second dory in line and, within seconds, are making our way into Soap Creek Rapid. Sitting next to my wife, I believe I can feel her adrenalin pumping in rhythm with my own. Blinking one’s eyes is slower than the speed at which the first splash comes out of nowhere, crashing into the dory. The cold water begins to compress the air from my lungs, a second bigger wave finds entry into my jacket and a path down the back of my neck – my remaining oxygen is now gone. I gasp and try to refocus my river-washed eyes in time to see a third wave about to finish filling our floating pool. With feet chilling faster than thighs, the water is almost bearable around my waist compared to the ice wrapping my shins as body heat retreats into my torso. The command to start bailing is a terrific distraction. We unhook the plastic laundry soap bottles with their bottoms cut off and caps screwed on tightly and begin heaving water out of the dory at a gallon per throw. Hysterical laughter of having survived grips us, alleviating some of the cold. We keep on bailing.

Anxiety gives way to exhilaration, the skill of the boatman moderates the fear, and the falling of tension allows our minds to relax into observing our environment clearly. Our eyes not only focus on the white turbulent chaos of the rapid but are now beginning to take aim at what else is here as the river begins its churning descent through the constriction that whips the calm into whitewater.

The first element of beauty our gaze takes pause on is the “tongue.” The tongue is the part of the rapid where the water is at its deepest. In these seductive yards of river that drag us into the heart of fury, the flow becomes a smooth undulation of glass where, for a few brief moments, an almost frictionless silent calm delivers the dory into perfect harmony with its environment before crashing into reality and thrusting us into the rapid. Next up are the “pour-overs,” where a smooth sheet of water tumbles over a buried rock wall or large boulder, creating a water curtain hiding the danger before the falling water begins its churn into whitewater. On our sides, shallow rock gardens, often covered in tendrils of algae, agitate the water, acting as dire warnings to stay away from the edges of the river.

We are learning the language of the river with the hope of finding a growing comfort with its expression. The better we can read the fluid signposts, the easier it becomes to pay attention to the complexity of details and anticipate what our boatmen require of us to maintain an upright dory and dry passengers. Today, it is dawning on me that our boatmen read a rapid as we might respond to cues as we drive our cars at home on city streets. We are taking our first baby steps in learning how to navigate the road ahead.

Anonymous sandstone cliffs rise above us, casting long shadows. They have names we’ve heard before, but today, they elude us. This layer cake of history stretches over hundreds of millions of years, represented by what at one time was more than 25,000 feet of earthen deposits. Some are of marine origin, while others formed as mountains crumbled, deserts came and went, and winds scattered what was left. As geologists moved into the Canyon, they identified the age and composition of the geologic record in this grand display. They brought order by assigning names to layers, helping one another know what period in the historical record others might be referring to. Tapeats, Coconino, Kaibab, and a multitude of other indecipherable names would come to identify the rock from top to bottom. Deep below, in the basement, they found Vishnu Schist. Two billion years of Earth’s history were exposed to the prying eyes of a people looking to understand our origins.

Canyon details begin to move into focus and become defined as the boatmen point to specific features. Folds, uplifts, fault lines, erosion, rocks, falls, patina, coves, and seeps will enter our vocabulary and take their place in our memories. We will encounter fossils underfoot and high overhead throughout these days. Plants grow from impossible locations: on quarter-inch-wide barren rock ledges or next to the tiniest trickle of water being squeezed through millions of tons of petrified sediments.

Fluted rock must surely be some of the most intriguing displays created by a chance encounter between a random stone, solid rock, and water. First, a stone of appropriate size must find its way into a depression or chip on the top of a stationary rock. Water flowing over the surface of this rock and the loose stone produces turbulence, spinning and rattling the abrasive stone. Years pass with the tumbling agitation slowly drilling a cavity to form an ever-deepening pit until one day; it has created the distinctive flute-like shape we see next to the river. Over time, the loose stone causing this phenomenon erodes and disappears from the pocket it created. The process takes a pause until another stone on its way to the river falls into the flute, and the excavation continues.

We are about to get serious. It was announced this morning that we would be wearing helmets today; that point is here. On the approach to House Rock Rapid, we pull ashore. The boatmen need to scout the conditions of the river, which has broken into a loud roar. They huddle, point, and confer as their collective experience brings the group to a decision on how they will guide us safely through the next giant. “Helmets on!”

Our dory glides sideways on the tongue of House Rock Rapid, and with a deft and mighty pull at the oar, Bruce points our boat downstream in an instant. We skirt a wall of water, slice through a wave, and shimmy over raucous whitewater while excitement rules the flow of things. In seconds, it’s over; the helmets come off. This was the first rapid where helmets were called for, and there weren’t two gallons of water in our footwell. Our appreciation for the skills of the boatmen soars.

Soon, we’ll be passing mile 19 and entering the Twenties, the 10-mile stretch of river with the highest concentration of rapids in the Canyon. We are promised that more thrills are approaching. For me, the thrills have been coming on for quite some time. It was almost a year ago in November when we first learned of the cancellation that would allow us to sign up for this adventure. Over the ensuing eleven months, not a day went by that didn’t see me thinking of our launch date and what this trip might have in store for us. I read a dozen books, studied maps, sought out photos, watched videos on YouTube, and devoured every Grand Canyon documentary I could put my hands on. Our deposit check was signed on my wife’s birthday during a walk in the snow along the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. On Memorial Day weekend, a short road trip from Phoenix brought us to the North Rim for a couple of days of hiking. On the way, we stopped at Lees Ferry to stand on the beach and imagine that in less than 60 days, we would be boarding dories from here for the beginning of what we anticipated to be the most exciting adventure of our lives so far. In other words, that a big rapid should hold any particular excitement is muted by the fact that each and every second today surpasses any ideas I had during those months of waiting and wondering what the best part of a Grand Canyon river trip would be. Add to that a growing recognition that it will prove impossible to extract any single greatest moment, as I have already experienced so many of those in just the first 24 hours.

And before you know it, another small beach is taken as our midday dining room. Today’s lunch plans move like lightning. Within minutes of landing, the Pringles, PBJ, and sliced fruit table is up and being crowded with hungry explorers. The main table requires an extra few seconds before last night’s leftover salmon is unpacked and set next to two large bowls of cream cheese, one colored reddish by sun-dried tomatoes, the other green by chiles. Sliced avocado, tomato, lettuce, and onion to be stacked thick on a variety of bagels completes the offering. Forty-five minutes later we are fastening our life jackets and taking our seats to see what’s next.

Once more, the river is still and we float, forward, backward, sideways. Sometimes, we are close enough to other dories that the boatmen chat; at other times, we drift alone. Bruce directs our attention overhead on “river left.” River left and right is based on the perspective of facing downstream. Up there, he points higher, there in the overhang – the fossilized impressions of nautiloid shells are seen. Maybe 100 feet above the river lies the record noting the existence of early mollusks. They are now locked in the petrified sediments of the Kaibab Formation after coming to rest on a seafloor at the end of their lives a couple hundred million years ago. These nautiloid impressions are a fragment of Earth’s past on display for a few lucky people rowing by millions of years later. For a moment, we are like worms tunneling through the planet’s history.

Again, rapids approach, but this time, Bruce invites one of us upfront to try our hand at bow-riding. Caroline takes the honors and climbs out atop the bow for a ride through Silver Grotto Rapid. She grabs hold of the bowpost and crosses her feet to lock her ankles together, thinking, “Just how different is the view of this rapid going to be? Will I get wetter up here? What are the chances of falling off?” On the bow, you sit high above the dory, seeing all sides of the rapid. The bow dips momentarily and then begins to climb the first wave, thrusting you to thrilling heights before reaching the fulcrum of the wave and dipping again on a race deep into the trough that appears much deeper than it really is. Just as you think there is no end to going down and you are about to submerge, the dory starts its ride up the next wave. The bucking bronco is in full swing. Going from an exhilarating lift and thrust forward to plunging down and low, Caroline holds fast to the bow post, but the ride is all too soon over. Climbing off her perch, the excitement is reflected in her eyes and is captured in her smile. She exclaims, “That was amazing!”

With so many other things occupying the senses, I had hardly noticed the overcast skies following us until the cloud cover started breaking apart and blue began to peek through. As the shroud lifts, not only are blue skies showing promise for the day ahead, but the sun is spilling onto the landscape, heightening my appreciation for the complexity of color, depth, and warmth being displayed down the river. On top of it all, the lighting director in the heavens sends fluffy clouds streaming across the sky, with pillowy shadows running over ancient canyon walls. Nature performs her billions-year-old encore, and I am there to witness it.

As if on cue, enter wildlife stage left. A lone bighorn sheep, standing on a rise, demanding our attention. Each and every boat slows to a stop, allowing us to ogle this tough animal that has adapted to survive in this hostile environment. Patiently, he stands his ground, affording all who wish to admire him a moment of reverence. This guy must be a late bloomer; I think I count four rings on his horns, putting him at about four years old. Alone, either he hasn’t found his own harem, or a more dominant male has taken his ladies. Judging from his size, he is going to have to toughen up before taking on one of the older alpha males who has had many opportunities to engage in the ritual of violently butting heads with young bucks, as is the requirement for maintaining a grip on the herd.

A great blue heron resting on a mangled pile of boulders was spotted before lunch; it was blending in with the brush behind it. Standing nearly four feet tall, it should have been easy to see, but these birds are masters of camouflage in their perfect stillness. We might have been able to catch a fish or two by now, but no one brought a fishing pole, so they will remain safely below the surface of the river, out of sight. Bird calls echo along the cliffs. The few remaining otters and beavers that live here are rarely seen. Only the slick mud paths on the river banks that identify where they have slid in or out of the river offer a hint of their presence.

Bruce offers me the catbird seat for the next spectacle. My perch is also on the bow but in a slightly different position. I’m instructed to lie on my back and look up. Bruce then maneuvers the dory closer to the 600-foot sheer wall of Redwall Limestone. Just as we’re about to collide, he turns the boat so my head is perpendicular to the rock face, stretching up like a highrise whose top has disappeared into the heights above. We float sideways downstream as the rust-colored wall scrolls by like a giant papyrus roll. This is my first encounter on the river with giddy, nearly tearful ecstasy. I am struck with astonishment that this perspective shift should be affecting my emotions so powerfully. For these moments, the dory, river, and everyone else is gone, leaving a sheer rock face as the only reminder of the Earth that is floating below the sky.

Minutes pass, though it could be hours, one turn around a corner, maybe a dozen miles were traveled, or had the boatmen only made three oar strokes? Time and space have expanded. An out-of-place wall of green snaps back my attention that was wandering in dreams of beauty. My eyes follow the climb of plant life upward from the waterline to where monkeyflower blossoms, ferns, moss, and poison ivy grow until, to my surprise, I recognize what feeds this riverside garden – a waterfall pouring from the solid rock wall. And now I, too, have discovered Vasey’s Paradise just as John Wesley Powell did back in 1869. For this one time, I wish the dories to move faster, to bring us closer in the blink of an eye. And once our dories finally close in on this lush oasis, I’ll do my best not to blink again, or else I might miss a fraction of the detail appearing before me in this hanging garden of wonder.

Here, I learn the first curse of a river trip down the Colorado. We are on a schedule. Not a rigid, daily schedule necessarily, but under guidelines from the National Park Service, our time in the Grand Canyon is limited. We are only a few of the 15,000 people annually who receive permission to spend vacation time in an environment that can only accommodate so much traffic before the ecosystem is overwhelmed. Of these, only about 300 travelers will make the journey on a dory – how lucky we are. While one can dream of sitting here at the foot of this waterfall, named by Powell himself, for the stretch of time that would allow full appreciation of this slice of perfection, we will not find ourselves here for long, as we have a date further downriver and must move on.

A dip of an oar spins the dory, and entirely new perspectives unfold. Now receding from our view, the hanging garden shines in a different light, asking if I shouldn’t consider this to be the best view of paradise. And then, with a heavy heart, we are gone, and it, too, must now compete for headspace in my memory.

The pace quickens. Rondo guides the way, rowing with determination, pulling dories and rafts into his wake. The narrow canyon begins to fill with the light of the golden hour of the afternoon as the lead boat shrinks in the distance under the approaching sunset. Ahead, we are not seeing a mirage but an epic landmark, confirming that its existence is not only a mythical, often photographed legend but a real place. A place that we are rowing toward and about to land on. Redwall Cavern grows larger and more amazing with every dip of the oar propelling us toward its giant beach. Was it mere chance that delivered us to an absolutely silent and empty Redwall Cavern that would be ours alone? Or are these boatmen masters of their domain, in tune with the seasons, the sun, and the schedules of others who may be sharing the river with us?

We have landed. Stepping from the dory is like exiting the Apollo capsule to place one’s foot on the surface of the moon. Climbing through the deep sand simulates the slow-motion, low-gravity walk that lets me know I have left my own familiar planet. As quickly as my legs can carry me, I race to the back of the cavern so I can have the view from within, looking out. This is the stage many others before me have stood upon; now it is my turn to explore the shadows and bask in the red glow of the reflecting canyon wall from across the river that is shining its spotlight into the depths of the largest riverside cavern in the Canyon.

The rest of the group is crowding around a boulder not far from where we disembarked. A cluster of fossils, including a crinoid and a mollusk impression, are closely examined and discussed. A Frisbee sails into the cavern, and the chase begins, as some will play a brief game here on the Colorado River for what is likely the one and only time in their lives. Others just walk around, taking in the immensity of this natural shelter. Then, out of the quiet, standing in the center of this nearly 60-foot wide, 20-foot tall, clam shell-shaped cavern, our boatman, Katrina, has begun singing a cappella, “Nothing But The Water” by Grace Potter. In full volume, she lets go and fills every inch of Redwall Cavern with her commanding voice. To everyone’s delight, she delivers an encore with a rendition of “A’Part” by Elephant Revival.

Sadly, camping is not allowed here, although this makes perfect sense as neither our visit nor anyone else’s would be as delightful if, upon arrival, we found ourselves maneuvering around tents, chairs, and a camp kitchen. Speaking of camp, with the warm light of sunset fading fast, it is time for the 22 of us to go find a home for the night. Luck remains on our side, as not a mile downriver, Little Redwall Camp is empty and about to be ours. Dories and rafts pull up to the steep beach; boatmen drive their sand stakes deep into the shore to tie down and secure their boats. We, passengers, form a relay, passing gear up the beach to get rafts unpacked, allowing us to set up our tents and the boatmen to start the pampering dinner ritual.

By the time we are settled in, appetizers are on offer, and we start to relax, except for one of us. The first display of Great Determination has me gasping in shivering empathy. Fellow passenger Phil, armed with his soap and a lot of courage, steps gingerly into the icy waters of the Colorado in an attempt to bathe. While knowing I should respect his privacy, and although I wouldn’t normally make it a habit to watch another man wash away the accumulated grime of the day, I stand mesmerized at his ambitious move to be first among us to immerse himself in the mighty Colorado. Mind you, Phil is wearing his river shoes so he does not stand fully naked before us. The shorts that adorn his lower torso also help keep the view family-safe. Trying to get his head underwater is no easy feat, as poor footing nearly threatens him with a swim. Phil quickly wisens up, opting to splash water over head and shoulders, as I feel it’s time to drop the staring and let him do what I’m still far too afraid to attempt. I’d have applauded his gumption had I not been trying to be at least a little bit discreet, though I do feel I learned something from his experience in how to make the best out of trying to clean delicate parts with ice water.

We warm ourselves around the night’s fire, some pulling in to inch their feet closer to the source of toasty delight. Neighbors talk with each other to discuss the events of the day, and we learn headlamp etiquette to avoid blinding one another with these piercing LED beacons protruding from our foreheads. Here and there, a beer removed from cold storage is being enjoyed, and others are content getting lost staring into the soft flames of our well-groomed campfire. Behind the fire circle, Andrea Mikus, whose day job here on this river trip is to row the raft that carries the toilet, prepares our evening meal with Jeffe by the light of a lantern.

Some passengers talk, others are journaling. Out of the dark, the trumpet of a conch shell sounds, and its mighty echo pronounces that dinner is now ready. We line up, and within minutes, plates are full, but nearly as quickly, they are once again empty. The sound of the conch highlights a special connection for me as more than a few of our friends are Hindu. In Hinduism, the god Vishnu carries a conch. It is said that the sun and moon reside in it, along with Varuna, the god of sky and water. Also represented in the conch are Ganga – the river goddess – and Saraswati – the goddess of knowledge, music, art, and science. The sound of the conch is thought to drive away evil spirits and is linked to the sound OM said to be the breath of Vishnu. Here in the Canyon, we will find ourselves learning of the basement rock called Vishnu Schist and the peaks known as Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva – named after the gods of the Hindu Trinity.

Just when you think it’s all over, dessert is announced. Slabs of Dutch oven-baked chocolate cake are handed out. While we are devouring the sweet, Rondo interrupts the wolfing of the last of our crumbs, “Hey, you guys, and especially you new guys! How about those cooks?” A rousing applause goes up. Rondo proceeds to go over what was accomplished since our launch this morning, recapping our time on the river and in the Canyon. This leads to what our loose agenda for the next day might be, “Coffee club will be really early, followed by a yummy breakfast.” He continues, “We would like to be out of camp before 9:00 – tomorrow will be similar to today, only different. From there, we will do any number of things that will be determined by factors to be considered over the course of the day.” Out from the darkness, Bruce speaks the sage words, “Indecision is the key to flexibility.” If other details or options were spoken of, they were lost to a mind filled with the enormity of the day’s experience.

The conversation fades further from my hearing as my attention is lost to the brightening night sky. Somewhere out of view, the moon is providing evidence that it is crawling over the horizon. The stars that were set against a dark sky began to fade with the increasing blue luminance that was crowding out the black. I sit next to the fire, but I am hardly here.

My reference points of familiarity are gone. No streets, lights, or signs are here to direct what is where or what comes next. The sliver of sky overhead offers not a hint of the cardinal directions unless one can read the stars at night or spot the sun and glean the arc it is tracing overhead during the day. Depth is immeasurable as each view is infinite, the eyes and mind unable to catalog the magnitude of what is present. Any attempt to see it all is quietly answered with a calm sense of surrender. It is as though an inner knowledge or instinct is ready to leave dormancy and remind my frantic being that not all is to be known, understood, and then anticipated. There is mystery left in nature, but we must shut down expectations and allow ourselves to find calmness that will invite the inexplicable to show us what has been forgotten in our rush to certainty.

Drifting here through self and Canyon, I grow ever more distant from my own contrived universe of time and location. I shrink, moving further and deeper into the unknown world. My sense of the primitive grows larger but is far from being embraced; it feels alien and odd, just as I was taught in school. Escape velocity from the known universe occurred; it must have, but just when that happened, I cannot tell. The known is lost in this extended moment of infinite possibility. When precisely did I leave? How far away am I? Lees Ferry might be the starting point, the physical node of entry for sure, though if I think long about it, I’ll likely see the starting point stretching back as far as I can recognize my own rise in life. But for the here and now, it was there in the gravel next to the Colorado River where a couple of vans dropped me and these fellow travelers on that day we piled into dories and bid farewell to the familiar and the certain.

Considering all that has been seen and experienced, from riffles and rapids to fossils and stories, canyon walls and wildlife, hot meals, cold lunches, song, and campfire, I must be further away than I am because I cannot find the exact moment I left, and without that, how should I figure how much time has passed between then and now? Asking the others in my immediate proximity what day it is, they demonstrate the same dawn of awareness as I – they, too, cannot be sure. Someone guesses Sunday, which brings up the question, “Well then, what day did we leave?” Another voice interjects, “I think it is Saturday,” and then, “I thought we left Friday.” But that would be….yesterday? Eyebrows dip, foreheads furrow as the wheels turn to determine if we believe this information to be correct. It is on all our faces, disbelief that it may very well have been just the day before, less than 36 hours ago, that we got underway.

But we’re not done with this day yet. Jeffe is about to tell us a story, the story of his friend Joe Biner. He begins with a question, asking if anyone objects to some rough language; no one does. Jeffe then reassures us that his impression of Joe is offered with all the respect and love his friend deserves.

Joe is a fishing guide. He has an incredible love of adventure, dry humor, and a blistering tongue when it comes to cursing, and he also has cerebral palsy. Moving into character, one admired and complimented on for accuracy by Joe himself, Jeffe starts to speak in a contorted, twisting and writhing, cerebral palsy-inflected voice of strained and stammered cursing, mixed with brilliant humor, telling us about Jeffe’s and Joe’s traveling down the Colorado together. We also hear of a particularly funny story of Joe meeting a client who had contracted him through his outfitter service for a weekend of fishing. After arriving at the tiny rural airport, the client waited for his guide to show up until just the two of these men were left in the terminal.

Joe holds his ground while his potential client paces, looking for his fishing guide. Well aware that this man is not considering that the guy in the wheelchair could be his guide, Joe looks on as though he, too, is waiting for someone who hasn’t shown up. The waiting continues with an occasional polite smile and nods exchanged, but not a word. Finally, it happens:

“Man, I wonder where my ride is?”

Joe speaks up, “Yeah, I’m wu-wu-wondering wu-wu-where the guy I’m supposed to take f-f-fishing is?”

The wheels turn, but not on Joe’s chair; the dawning of awareness takes rise on the client’s face.

“But I’m supposed to go fishing this weekend.”

Joe says, “Wu-wu-well then, llllet’s get going.”

“Um, well, how….?”

Joe then blurts out, “I’m about to leave this fu-f-fucking airport and drag that b-b-buh-boat waiting outside to the river for a wu-w-weekend of great fishing, but mmmaybe I’m going alone. You c-c-c-can get over yourself and get to fishing, or you c-c-c-can go back home.”

The two went fishing, and we learned that Jeffe, in addition to being a great river musician, is a talented storyteller, too.

At the end of the story, the majority of the campers depart to do just that – camp. Into the darkness, headlamps mounted to foreheads trace trails to the camper’s respective tents, each disappearing with a zipper pull that seals the occupants in for the night. Most of the boatmen have quietly left to take up their floating beds on the river. Once more, we remain with a small group around a dimming fire. Andrea gently strums her guitar. The unseen but present full moon is still on the rise; just a couple hundred feet across from where we sit, the canyon wall has started collecting moonlight. If we can stay awake long enough, I hope to see moonbeams sparkling in the Colorado. Andrea softly sings “Harvest Moon” by Neil Young while the tiny fire’s warm flickers offer momentary glimpses of faces still holding on to experiencing every second this perfect day has brought. Linda, who is Andrea’s mom and is along as a swamper and guest of her daughter, wipes the tears that have spilled down her cheeks, obviously touched by the moment next to the river, feeling the music, seeing the moonlight, and being with her child in her element.

Caroline and I leave to slip into our riverside nest, skipping the tent in order to better watch the effect of the full moon brightening the walls around us. Not yet 9:00 p.m., we fight heavy eyes with minds that want to forever hear the river and to always remember this moonlight-infused night. Right now the Earth is nothing more than a narrow crack that is the Canyon we are lying in, with a gentle river flowing through. The music of the Colorado plays on, and we fall to sleep.

–From my book titled: Stay In The Magic – A Voyage Into The Beauty Of The Grand Canyon about our journey down the Colorado back in late 2010.