Against a backdrop of thunder, our day began with a short walk over to Café Dillenburg, formerly Brot & Freunde, to fetch our daily bread. After breakfast, with no time to dawdle, we were just as quick about catching the subway to Hauptwache and then another to the Hauptbahnhof, where we boarded yet another train to Geisenheim. Along the way, we passed Königin Viktoriaberg (Queen Victoria) Vineyard in Hochheim, named after a mid-19th century visit of the queen, but we are not out for sightseeing today; that begins tomorrow. Today, we are spending more time with family.

At our train stop in Mainz-Kastel, our train was joined by a couple of young Ukrainians carrying a wine bottle and apparently already drunk here at 9:30 in the morning. Their boisterous voices weren’t going to be tempered, regardless of the amount of stinkeye the people sitting around them were sending their way. No matter the difficulty in being away from home due to your country being at war, you are ambassadors of Ukraine, leaving impressions on the people helping fund your efforts and offering you refuge.

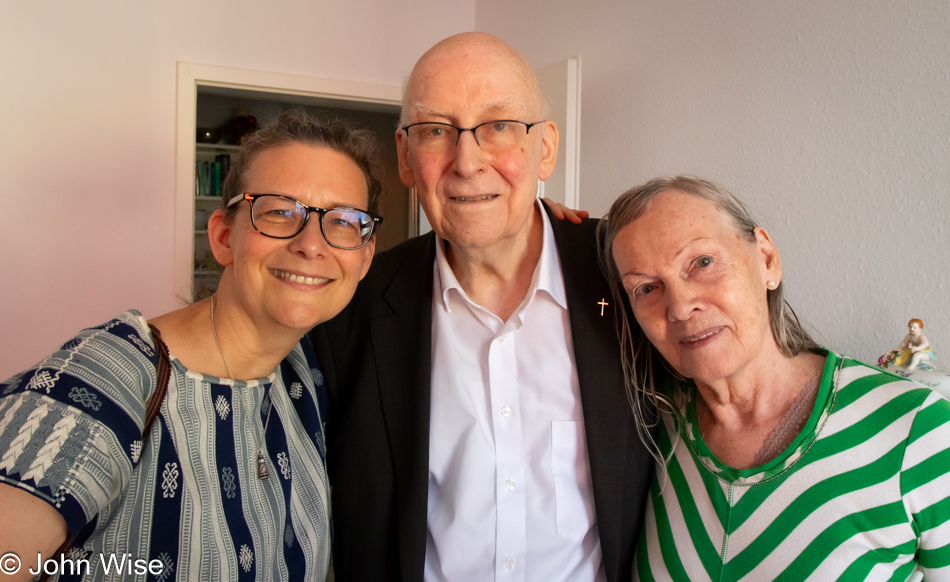

Pulling into the station at Geisenheim, we’d chosen precisely the right car to sit in and the right doors to exit because right there before us was Father Hanns, happy to greet us. Caroline’s father is working on closing out his 90th year so he can lay claim to having reached that rarified age that is the decade before one might see 100 years of life. While Hanns offers up a few anecdotal issues about having reached this point in his life, it is not easy to see age overtaking him yet. Sure, he struggles with his eyes, and a cane is part of his outfit. Still, his mind remains deeply curious, though momentarily troubled by his ongoing struggle to part with books that have been constant companions for the majority of his life.

Father Hanns is giving up many of his books because he is moving to Geisenheim full-time after maintaining a small apartment/bungalow in Karlsruhe for decades and commuting between the two locations. Vevie (or Maria, as Hanns affectionately calls her) has been living on her own in Geisenheim for much of that time, but it has become apparent that she needs more care. Remembering how difficult it was to shed a majority of our books when we moved from Germany to the United States in the 1990s, I can hardly imagine how hard it must be for him to have to part with so many beloved books, many of which are family heirlooms.

Over a bottle of sparkling wine, the four of us sat on the terrace to talk while the skies were clearing. For the better part of 90 minutes, I tried pushing the conversation back to German as Vevie’s frustration at not understanding the English we were speaking was bedeviling her. This wasn’t quite so dramatic on previous visits. For Father Hanns, exercising his wit and humor in English allows his inner rascal to make an appearance as he so enjoys jokes and wordplay and, these days, probably does not often have the opportunity for banter.

I’d imagine that for an intellectual with German as their mother tongue, proficiency and control of linguistic complexity in German are taken for granted. In English or Hungarian, Hanns has the opportunity to spin tales with a flare that exemplifies his love of a broad body of knowledge that likely surprises and delights those he enters conversations with.

By noon, it’s lunchtime for Caroline, Hanns, and me, as Vevie prefers to stay in. Leaving the apartment, I spot the collected works of Arthur Schopenhauer, which is one of the authors Hanns cannot part with. At the nearby restaurant with an odd mix of German and Indian food along with a fairly extensive pizza menu, Hanns is able to open the throttle in English. The conversation turns to the social side of politics and after a blindingly fast 2.5 hour spent at our midday meal, it’s nearly time for Caroline and I to catch our train back to Frankfurt. In a parting thought, I offer to return to Germany later this year or early next to spend a couple of weeks talking philosophy, religion, and social responsibility with my father-in-law.

Back in Frankfurt, we visit Jutta once more before taking off to other lands tomorrow. While Caroline and her mom were chatting, I sat out on the balcony catching up on my note-taking when one of the orderlies named Rouven Dorn, whom I’d met a couple of years earlier, came out for a smoke, and we got to talking. Turns out that he, too, is a fan of Schopenhauer, and upon hearing we are heading to Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, he shared that his favorite Swedish metal band is called Sabaton and that I should take a listen to No Bullets Fly and Lifetime of War. There was more to the conversation, as there always is, but those details are lost in the ether as nothing more was shared with my notebook.

Another day, another demonstration.

I believe this is an anti-Taliban and consequently an anti-Pakistan demonstration as from my reading of their call to free Ali Wazir, they are voicing their displeasure with Pakistan’s support of the Taliban and that Ali Wazir was arrested in retaliation for his anti-Taliban stance. But I didn’t stop and talk with these young men since my German is not good enough to have a discussion about politics and how they relate to Afghanistan and its neighbor to the south. I do, though, respect that this kind of public conversation and display of concern is alive and well in Germany, even if it pales in comparison to the determination of the French to raise their voice.

There will be no burning of the proverbial midnight oil, no sit-down dinner, and no wandering in nostalgia as we have an early flight in the morning and need to be packed and ready to go this evening. With that in mind, dinner for the second night in a row will be Döner and while the place is called Döneria, it’s different enough to not be as amazing as the one in Bornheim. Funny that I can try being picky while I’m here when it’s been two years since my last Döner, but with the limited number I can possibly eat while in Germany, I need to make the best of these opportunities.

There’s a strange side to what I find so familiar. I know that within some number of years, I will never gaze upon any of the sights that were so common to my senses at the times I was present. I will have passed away. Those who are but teenagers on that day I die will be traveling in their own routines past the familiar and won’t have considered yet how anything changed over the course of years others were familiarizing themselves with corners of a city. Nor will they be entertaining ideas that their time to be witness of the places they may be taking for granted will pass out of their view as yet another person picks up another new relationship of seeing a place as part of their unique life. This though is the nature of life; we all pass in and out of the places we’d love to fondly remember forever.