We were on the Puerto Caté San Cristóbal de Las Casas road, passing through the tiny village of Cruz Quemada, when I spotted this small chapel. Our road trip today is taking us right past Chamula which we visited yesterday, but our destination now is further north in the village of San Andrés Larráinzar, with a population of only 2,364 people. If you look over towards the left, you might notice that we are above the clouds.

After a little bit of rain a couple of days ago, the haze has cleared offering us a great view of the surrounding lands. If life wasn’t difficult enough in rural Mexico, we learned about unsavory characters who desire particular plots of land and frame the current occupants if they refuse to sell in an effort to pressure them to leave. Selling land is not a solution to anything for these indigenous people as what would the seller do after leaving lands their families have tended for decades or longer? So the bullies accuse the man of the house of some crime to entrap them in the legal system for years and pressure the women to sell in order to help their husbands or sons get out of prison. Land ownership is a difficult case to prove when documentation is thin or non-existent and so preying on the vulnerable is a lucrative business that only produces tragic results.

As though living on earnings of $5 to $13 pesos a day wasn’t a difficult enough existence, imagine losing your small plot of land on which you grow squash and potatoes to feed the family and your small decrepit buildings housing a kitchen, sleeping area, and shelter for your chickens were then all gone. There is no state aid for you, no small business administration, no bank loan: you are on your own. It could be argued that the rabbit eats the vegetables, the coyote eats the rabbit, the wolf kills the coyote, the bear devours the wolf, and so we have to recognize that we live in a dog-eat-dog world where there’s always a predator and always someone or something to prey on. But in the US, we have the luxury of living in a country of rules and order where believe it or not, we at least have a modicum of empathy for those on the margin, to some degree anyway.

Mystery surrounds us as I have no ability to learn what mountain range I’m looking at, what the valley is that stretches off to the left, and what the church or chapel is on the top of the hill to our right. Not that I need to know any of that, as I’m appreciative that our guides have a body of knowledge of the surroundings and that they’re sharing these out-of-the-way places with us. We don’t simply move through looking at the sights; we have a purpose, and we are likely going to find delight, treasures, and lifelong memories when we reach the destination in our itinerary.

We’ve reached San Andrés Larráinzar and the first of three families we’ll be spending time with today.

At least for another decade or so, you will not escape the ubiquitous backstrap loom that is everywhere here in the Chiapas Highlands, but after that? Will youngsters be able to avoid the allure of jeans and comfortable t-shirts as they eschew, wearing scratchy wool and suffering from the constant toil of hard work that they are barely compensated for, or will the young abandon the places and traditions that create the delightful reasons for our visit?

And now the treasures of untold wealth. In the United States, I buy the most non-descript, boring short-sleeved shirts of no particular character made from massive sheets of fabric, likely machine-woven in China. That fabric is sent to Bangladesh, where it is cut and assembled before being loaded onto a container ship to be sent to the store I’ll buy it from. Before reaching me, the cost to make that shirt was about $3.50, and then once I visit the store I’ll buy it from, the charge will be about $60, not due to shipping but because that’s the way capitalism works.

This is a close-up view of the dress that is pictured left of center in the photo above this one. It is not cheap at $18,000 pesos or $900 U.S., but it’s a handmade masterpiece of incredible complexity. In my estimation, the person who wove this required no less than 500 hours of work, meaning they are valuing their work, materials, and creativity at only $1.80 per hour. I’m writing this while back home in Phoenix, Arizona, and have to scratch my head asking if we’d missed an opportunity to own this work of art if even for a short while.

Well, this is peculiar; a man is at home. But it’s also an incredibly fortunate moment too. You see, there’s a pretty strong division of responsibility in households down here where men tend to the most physically demanding labor (usually outside the home) while women care for children, households, clothing, and some minor farming. Both sides contribute to the financial well-being of the family or at least strive to. Being on hand to witness for himself the respect and awe that arrives with us visitors armed with fists of cash must have the effect of convincing him of the value the women of his family are bringing not just to their own economic security but also how this impacts their small community.

The huipiles are seriously a canvas as the Maya are capable of dropping big art into their textiles.

Hello, little girl; where will your dreams take you?

Hello grandma, have your dreams brought you at least a little something from the hopes you had for your family?

What started out as just trying on a blusa led to one of the ladies bringing over a skirt for Caroline to try and then the belt. We left with everything but the belt. After verifying that wearing a belt Caroline picked up in Tenejapa last Thursday would be okay to pair with this ensemble, we asked the price of the pieces and gladly paid for them. While there’s a good dose of guilt in paying so little, we also know that collectively, we are helping sustain this family with our enthusiasm and generosity.

Do you see rebellion against fulfilling the role of caring for her little brother while the older women contend with those of us who might leave enough of our money to care for this family for the next year or beyond? This young girl, who I guess is maybe 11 years old, wears the rebozo that supports the young guy and ensures he’s close and loved while she meets her responsibilities. The baby boy has no reason to squirm or flail about while he’s held securely by someone so familiar. This is not a moment out of the ordinary where the players are unaccustomed to this routine, this is just a part of their lives.

I don’t have any idea what this lady will do with this weaving when it’s finished but I’d love to be around when it’s cut off the loom and is transformed into its next form. Its design can be seen ten photos above on its backstrap loom that she’s working on here in this photo.

Our visit is nearly over, but first, a group photo was in order.

What a beautiful day to be out in the highlands of Chiapas.

The whole time we’ve been in the San Cristóbal de Las Casas region of Chiapas and these surrounding areas, we’ve been in Zapatista country.

Zapatista mural on a school because indigenous rights are still being trampled by the dominant Mexican culture. While there’s been some progress for the people of the highlands, they are still the poorest and generally most undereducated people in Mexico. This primary school on the side of the road is in Oventic Village.

There’s a lot of information about the Zapatista movement out on the internet and in books, so this isn’t something I’m going to spend any more time on, but if you are interested, just search for Zapatista, and you’ll find a ton about it.

Our next stop is out here in the countryside.

The best I can do is guess what’s going on here, but my estimation is that part of her livelihood is derived from selling bread.

I’m pretty certain we are now in Tres Puentes, which is still a part of San Andrés Larráinzar, but this landscape is quite confusing to me. We are visiting the Jolob Home Decor weaving factory specializing in household textiles.

This is the one time we will see men weaving, though I think there’s a technical differentiation in that they do not operate backstrap looms but engage in the physical labor of operating a standing pedal loom where they must step on the treadles all day in order to complete their work.

It seems that the factory does short-run custom designs for companies around Mexico but also for international clients when they can snag a deal.

While I’m often looking at dressed looms at home, I never tire of seeing the multi-colored warps that are destined to become all manner of textiles.

This is a bobbin winder for winding weft thread on bobbins, which end up in the weaving shuttles. The contraption on the right is a swift. It holds the threads that are wound on the bobbins.

Here’s a two-shaft pedal loom working on a simple color scheme you might be able to make out under the white heddles, and then behind those on the right of the photo is the small space one of the men would stand all day to operate the loom.

Small consolation that at least these guys are working in fresh air up in the mountains as in the case of this setup, his back is to the window.

It could be a future towel, placemat, tablecloth, or something I’m failing to guess.

The boy is learning the ropes of helping the men in the factory. Should you believe this youngster would be better served by being in school, keep in mind that it costs a family money out of pocket every month to have their children attend a school to receive a formal education. Add to that, there must be a school nearby which often there is not one. So, the cycle of grinding poverty goes from one generation to the next, and then Americans wonder why, in another 5 or 6 years, the boy will make the 2,856km (1,800 miles) trek across Mexico to reach the Arizona border where he might earn more than $1 an hour with his near-total lack of education. Yet, he’s considered a threat to the jobs of Americans who’ve received a high school diploma.

No visit anywhere is complete before checking out the wares for sale. Caroline picked up some fabric.

Now I’m fully turned around and unsure of where we’re going exactly but I think it’s back through San Andrés Larráinzar proper.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll probably write it another dozen times this year, but I’m my own worst enemy, thinking I need all these photos to tell the story of where we’ve been with enough images to paint a clear picture of things.

If you build right up close to the street, you’ll have more space behind your house or shop to raise more stuff for sale.

I might have seen the sign into town identifying where we are passing through, or maybe I thought, this is obvious where we are as earlier in the day, we were driving in the other direction. But ten days later, while at home, I think I know that we are in San Andrés Larráinzar, but without Google or Bing Streetview, I wasn’t sure until I found someone else who posted an image of the church on the right at the top of the hill, it’s the Iglesia de Larráinzar. If I zoom into the full-size image I shot, I can see the similarities that verify that we are on the streets of San Andrés Larráinzar.

Are those the yellow arches of McDonald’s I see in the distance?

In rural Mexico, delivery services are not common, but young boys using tumplines to help carry the weight with their heads in addition to their backs appears to be a popular method of moving goods from one location to another. I’d wager that prior to seeing this word, most readers here didn’t know what a tumpline was; well, Caroline found this great article at The Atlantic that discusses them. (Spoiler alert: they have advantages over backpacks.)

Here we are. This is home for the next family we are visiting today, though this has greater significance for me as we are not here just for textiles. This encounter will be far more personal to me.

A year ago, when we first considered joining this textile tour into Chiapas, we were supposed to add on an extra week that was to take us into Oaxaca so that after Caroline had her fill of the fiber arts, I would have the opportunity to indulge myself with culinary treats and maybe some cooking lessons in the state of Mexico famous for their moles. But, we were reluctant to commit to so much time in Mexico as this was our first time really getting into the depths of the country, and Caroline was just then jamming into Duolingo, so she’d have some confidence of being able to communicate with others should we find the need to deal with a situation in Spanish. We chickened out, and now that we’re here and having such a great time, sure, we’d love to have an extra week, but we are without regrets. With the intense immersion with things as they are, we’ll be happy to go home in a couple of days and bask in all of this.

Today is special because I’m being offered, as is the rest of the group, an incredible opportunity to join a bunch of ladies in their kitchen who’ve been toiling on our behalf to make us our mid-day meal. I’m not being given cooking lessons, but I am being honored with a lunch made by the hands and hard work of Mayan women I could have never imagined making food for me.

These are just some of the women who collected the veggies and other ingredients that we would feast on. Someone or maybe more than one person dispatched the chickens this morning who apparently lived good, long lives before finding their way into the pot on our behalf. I point out their long lives as, without a hint of complaint from me, those old chickens were as tough as any mutton I’ve enjoyed on the Navajo reservation over the years. In the US, we slaughter our chickens when they are 47 days old on average, with breasts as big as the entire chicken that has joined our pot; there was no succulent, tender white meat here, but tons of flavor. Some of us just learned what it means to take the chicken’s life after it served a greater purpose.

The lady holding the gourd is going to bring it and its contents to the table in a moment; it holds fresh tortillas. Also on our table are two types of salsa; I prefer the green chili with citrus as opposed to the smoky red chili; there are small bean and cheese quesadillas, though I’m not sure that’s what they are called, and then there are quartered citrus that we are calling orange-limes for now until we get confirmation.

Update: I’ve just been informed the citrus is called – Limón Mandarina.

The hosts do not join our meal; they wait on the sideline, ensuring that their guests have their fill. To my surprise, Norma is asking for seconds before anyone else, followed by me, Caroline, and Gabriela. The chicken soup was nothing short of incredible.

In this dark, smoky, open space dedicated to performing kitchen duties, we sit not only in the shadows but also in the shadow of their Mayan shrine. We, outsiders, have somehow warranted being invited into their hearth, the heart of their home, and are allowed to sample the efforts brought to us in their sharing. Without being able to speak Tzotzil, I can never express my gratitude for their kindness and for making the culinary experience part of this journey complete.

You might ask, where does this rank in my food adventures? Easily in the top five. You see, it’s easy to exchange money in an elegant restaurant in New York, San Francisco, or Frankfurt, but having someone share the work that went into raising the chickens, growing potatoes and squash, and grinding the corn for our tortillas while receiving so little in return for such a gesture is the richest and most personal meal I can ever hope to enjoy. Real work and heart made my lunch, not for profit but for the good of a family and the souls of those invited to join them.

I was lucky to have Norma and the matriarch in the Cocina when Norma went over to thank her. I interrupted them to get this photo, which will stand out as my favorite of our trip organizer for the millions of moments she’s helped facilitate, but especially this one that has allowed me to find nourishment in a Mayan home in so many ways beyond food.

In keeping with the woven textile theme of our visit to Chiapas, this kitchen is made in the wattle and daub style. I’ll explain wattle is a process of building the foundations of walls using wooden sticks that are woven together before daub (mud) is applied. This method of building has been used for at least 6,000 years and is obviously alive and well here in the highlands. As for the kids, they too are made in an old-fashioned manner that pre-dates any of our architectural construction methodologies, wink wink.

After feasting, shopping but first some formal introductions.

Not to be rude but I needed time to digest my experience and consider what I and the others were just offered. So while the rest of the group listened to whatever it was they were listening to, I wandered the grounds, checked out a disused metate growing moss in the weeds, and allowed my imagination the space to find meaning.

Funny thing about serendipity: I was the first in the sales area, and this was the huipil that caught my eye.

It turned out that it was also the one Caroline wanted to purchase. She is sitting next to the weaver who created it. She must be a free spirit in her own way because she was the only one wearing a blouse in the style of Chenalhó, a different municipality. All the other women (and Norma) wore huipiles in the Magdalena style, which is pink and red.

The struggle of the Zapatista movement is never very far away in the indigenous lands of Chiapas and Oaxaca.

Is anyone else picking up on the Chinese blue-and-white ceramic thing?

From my perspective, the drying corn makes for a great decoration, adding authenticity to the idea of rural life. If I’m not mistaken, this drying corn has a purpose beyond the cosmetic and I simply don’t understand the utility.

Is this more corn showing up on the loom?

Maybe you are recognizing that the shirt on the woman to the right resembles the blusas from the first family we met today in San Andres Larráinzar and that everyone else is wearing the pink and red ones like the ladies who cooked and hosted our lunch? We are still in the region around Magdalena Aldama, and most women adhere to the attire that is traditional to their municipality.

This stoic and greatly dignified lady came out of the house and stood on the periphery with her granddaughter snug on her back; never once did she move for a chair or change her expression. I felt that she examined us, not caring a moment for what might be purchased or what world we emerged from; we were simply a ripple in the fabric of reality that darts into the dream and is as quickly gone. Her lesson to the toddler is to hold your own and be patient; everything passes, and nothing needs to be said as we’ll be right here long after they are gone. I’ll gladly admit that this is my projection of a romanticized notion and could as easily be so far off base as to be nothing more than fantasy, but vibes are vibes, and this woman has brought that.

This was a custom-made huipil for our organizer Norma.

I can’t look into those deep, dark pools of this boy’s eyes and not sense his desire to know what universe I look into when I’m not peeking into his small corner of the world. Is it my guilt of extraordinary luxury that wants to see an incredible hunger for knowledge and experience within this little boy? Can curiosity and wishes for comfort really be seen in a face, or am I again projecting what I want to see upon someone?

Then, on the other hand, there is this boy. I assume him to be the brother of the other youngster. He doesn’t have a care yet; he just wants to play.

But this stare is the look of knowing what’s coming. She is to grow up in a man’s world where much of the burden of existence will fall on her shoulders. Obviously, she can’t really know that yet, but this is not the careless, distracted face of a child without challenges. If someone told me that grandma took her on journeys into other realms to commune with the jaguar, I wouldn’t doubt that she’s gathering a sense of reality I’m too fragile to understand. Again, this is all over-romanticized nonsense from my own biases that have elevated the Maya people into something beyond the circumstances of someone who simply needs a warm bed, a hot meal, and a chance of a promising future where education and opportunity will be part of her life.

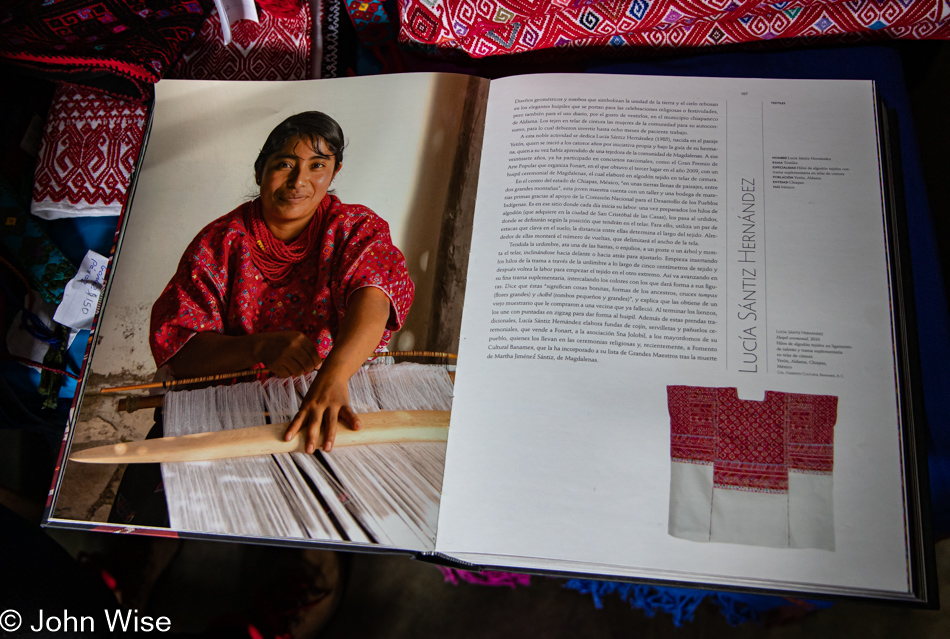

Lucía Sántiz Hernández is featured in a giant volume titled Grandes Maestros del Arte Popular de Iberoamérica – Vol 3, but I cannot find it available anywhere. Lucía is the woman above wearing the red and white blusa.

Here on International Support Your Local Weaver Day 2022, Caroline has settled on this huipil.

As everyone else finishes their shopping, I’m out staring at the clouds, trying to find something that differentiates the skies of Chiapas from the skies I look at every day up north. I want to see a difference, but I’m coming up empty-eyed.

Ten feet below, there wasn’t a hint of cell/internet signal, but up on the roof, the connection to the electronic gods of commerce was smiling down on the humans trying to pull money from some invisible place in a faraway land and with a magic handshake place money in the account of people who have already grown to trust the world of bits and bytes as much as they do of atoms and molecules.