The dark side of America’s cultural seclusion can be abated by the exploration of the internet and especially YouTube if one can figure out what to search for. On one hand, we live sad, tragic, and isolated lives cut off from most cultural influences aside from some benign facsimiles of authenticity. On the other, there are many people around the globe sharing unfiltered looks into crafts, foods, places, and customs that mainstream media has failed to cover except when they can be used for sensationalist and or propagandist purposes.

Take food: ethnic cuisines, as they are prepared outside of America, have mostly remained a mystery. For example, search for fried rice, and you’ll be hard-pressed to see anything that resembles the real thing as it’s eaten in Asia, but how would you know that if all the recipe sites, cooking shows, and local restaurants are only offering a type of dish that was designed for the American palate?

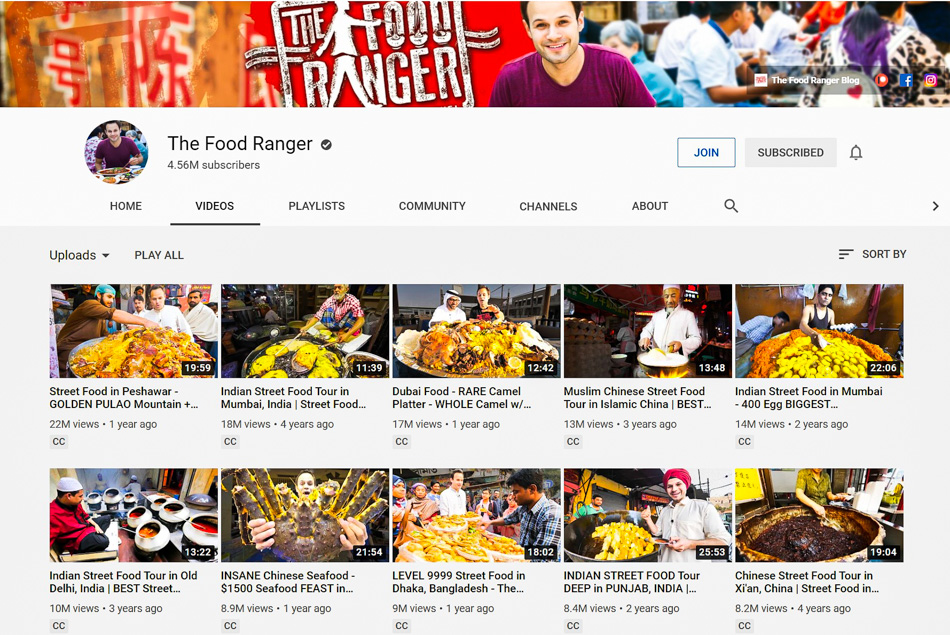

Somewhere between watching synthesizer videos and Russian car crash dash-cams, I must have seen a YouTube recommendation for a travel show from this guy named Harald Baldr. Through his travel exploits, I ran into the work of his friend “Bald and Bankrupt.” Maybe because I was binge-watching these guys traveling across India, Russia, Chechnya, and Belarus, I saw a recommended video in the sidebar for The Food Ranger, and something about it caught my eye. For the next weeks, I drove Caroline crazy with its host, Trevor James, and his particularly enthusiastic intonation of “Going Deep” into the local cuisine of wherever it is he happens to be.

What I was seeing from Trevor, aka the Food Ranger, were deep dives into street food across Asia with equal treatment for non-Western dishes surrounding various organ meats. Knowing he was fearless trying new foods and wasn’t squeamish in the slightest about any of it was a large part of the appeal. While YouTube was busy trying to get me to tune in to various other cooking shows of all the big American names, I was hooked on exploring a side of Asian food totally unknown to me.

Sure, Caroline and I had first tried pig ears, durian, and pork bungs (pig rectum and large intestine) more than a dozen years ago, and we were exposed to Indian home cooking years before that. I’d tried Ethiopian food while still living in Germany and had my first taste of Chicken Korma in Vienna before I’d met Caroline. What we didn’t realize was the breadth of culinary options and how often much of what is passed off as Chinese, Italian, Thai, and Mexican foods are seriously boring and far from their ethnic roots. Even when I learned how to make my own Lahpet Thoke (Burmese tea leaf salad – pictured), finding the ingredients in 2008 was nearly impossible. So difficult, as a matter of fact, that we had to travel to Los Angeles to pick them up as the online place in the U.K. wasn’t shipping the stuff to America.

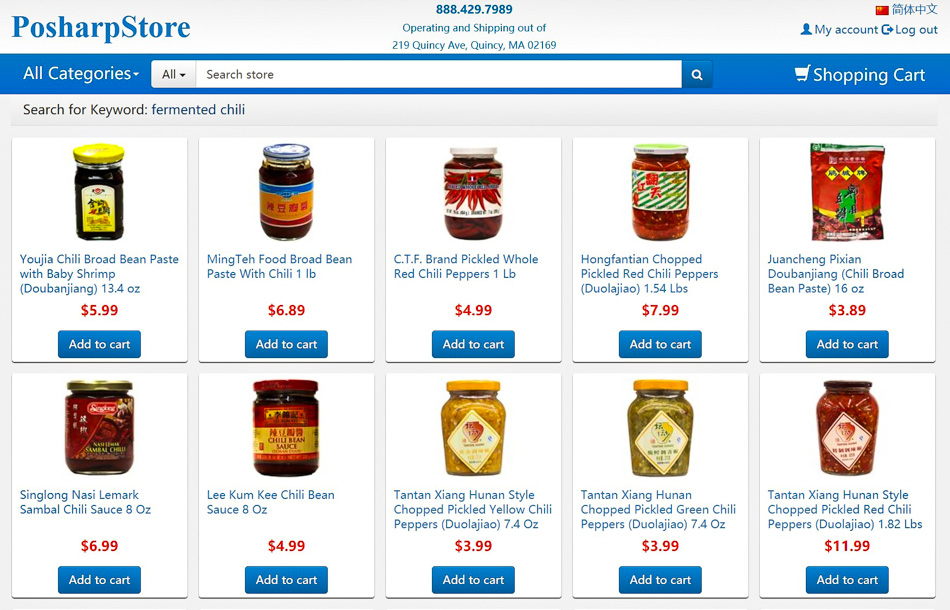

While we were culinarily curious, there were no guides for shopping at our local Asian stores, and back before the days of YouTube or even in its early days, there was no reference to see how someone might be using Zao Lajiao, and that’s if you could even find fermented chili sauce in America. The worlds of authentic Asian, African, and Middle Eastern foods remained largely mysterious and hidden.

Today, that is no longer true. After the Food Ranger, I finally gave in to another recommendation of this guy named Sonny with his food show, also based in Asia, called Best Ever Food Review Show. I was reluctant at first as I felt that Trevor was blazing the trail and how could Sonny do any better; well, I was wrong because the Best Ever Food Review Show was living up to its name. What I didn’t know was that Mark Wiens was actually the trailblazer of food reviews in Asia, having started his channel back in 2009. What united these three reviewers was their serious interest in exploring the flavors of the places they were visiting instead of presenting their content as an example of shocking their audience with food challenges that might put off others who’d be open-minded enough to try a new cuisine.

Learning about food is only a small part of getting to the point of trying it, especially if you aren’t ready to jet off to a far away destination for the sake of eating local delicacies. Next up were the people who could bring us into the actual recipes, and this is where Maangchi, Chinese Cooking Demystified, Seonkyoung Longest, Refika, Yaman Agarwal, and even Townsends have been paving the way to inspiring millions of people from around our planet. But even with guides to help show us how to make these dishes, we still need ingredients that are not always easy to find.

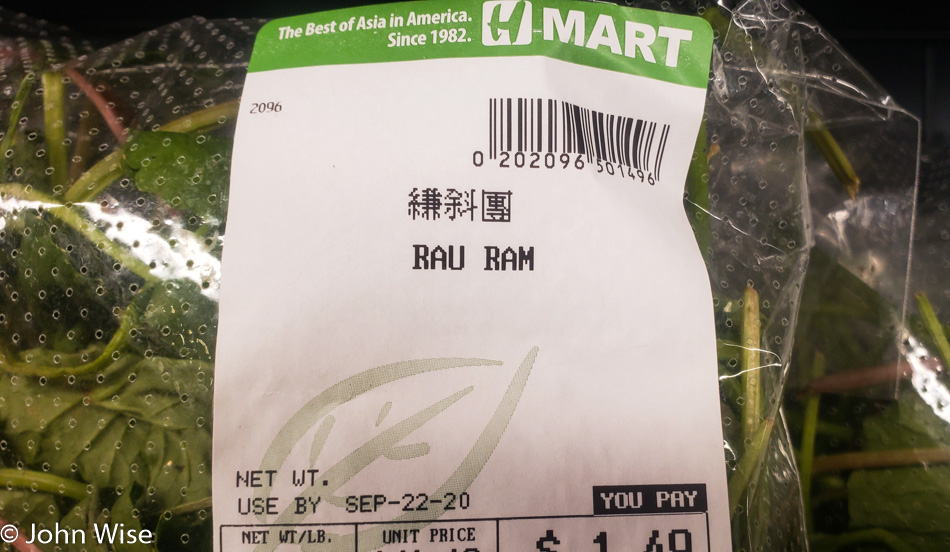

Amazon is one source for some ingredients, but local ethnic grocery stores are essential for many of the fresh foods that are required, and they sadly are not very ubiquitous across America. Even when we find a local Filipino or Middle East grocery, the inconsistent quality and visual appeal of these small stores might turn some people away. Other online sources can be helpful, but then again, you must first know what it is you are looking for, and while you may want to buy hing powder if the vendor knows it as Asafoetida and has it listed as such, you may never connect the dots to buy what you need.

The better cooking shows offer alternatives when they know particular ingredients will be hard to find for people in North and South America, along with Europe. Just today, I was able to find a single online source at The Mala Market for Er Jing Tiao and Facing Heaven chilies for making Ciba chili paste, but had I not found those, it was recommended I try cayenne and Thai bird’s eye. Another recipe I’m interested in calls for Duolajiao, preferably from Tantan Xiang, but it’s acknowledged that this is likely impossible to find outside of China, so an alternative was offered but with a lot of vigilance, I found that the PosharpStore in Massachusetts carries it, wish I’d known I would be buying this when back in August I bought Shaoxing rice wine from the same company. The point is that there are ways to get very close to authentic flavors, but you must be persistent in trying to source the ingredients.

Enter Liziqi, Laotai Arui, Dianxi Xiaoge, and WocomoCook, who are inspiring followers with their style of traditional cooking methods where we are viewing the gardens, tools, and environment where these foods are being made. There’s little attention given to the recipes and often there is little spoken, but the slow nature of bringing food into becoming a meal is an art unto itself. Now I find myself wanting a slab of tree trunk for my next cutting board; I’ve already bought a Chinese cleaver and have a Korean butane stove on the way so I can stop trying to use a wok on an electric stove.

Bring all of this together and add a generation of people from around the globe who are being inspired to move outside the bland versions of cuisine that hardly resemble its origins, and I find a new view of what ethnic dishes are being born. American renditions of German, French, Chinese, Korean, Thai, and Japanese foods are nothing short of sad atrocities using a set of homogeneous ingredients that have no variations from coast to coast here in the United States. Fortunately, there are still ethnic restaurants that won’t attract many Westerners anyway and so they have no choice but to maintain authenticity in order to be appealing to recent immigrants from those countries. As time goes on, I’d like to imagine that more people will be inspired by and start demanding these foods that, while exotic today, could become commonplace in the future.

Does anybody have some good tips on Icelandic, Iranian, Peruvian, Namibian, and Russian cuisines on YouTube? I’m also searching for Portuguese, Scandinavian, and Guinean streamers. By the way, as I was finishing up this blog entry, Caroline and I came across canned mutton at a local Vietnamese grocery and found a recipe from Guyana that we’ll be trying in the coming weeks. Another benefit of living in the age we are in.

** Note – not 10 minutes after this was published, I stumbled upon The Lime Tree on YouTube. My wish for Persian cooking examples has been found with this person yet another example of the influence Liziqi is having on cultural content surrounding food. I still need a person who walks me through the specifics of the popular recipes found in Iran.