Food is often just that, food. But here, where you wouldn’t expect culinary frills, the ritual of the meal has become theater. Can the kitchen performers best their earlier stage calls? They can, and they do. It is not necessarily that what is offered here can be said to be of gourmet preparation, nor is there anything exotic on the menu. Last night, we dined on barbecued ham with mac and cheese. Tonight, the boatmen will boil spaghetti to be served with a meat sauce and garlic bread. And this morning we are enjoying blueberry pancakes and sausages, but what strikes a chord are the fresh strawberries that have found their way into a fruit salad with sliced kiwi. Fresh strawberries on a nearly barren desert beach, five days downriver! Did someone parachute them in while we slept? Somewhere deep in the bowels of a raft or dory must be a magic compartment where avocados materialize, lettuce never wilts, and tomatoes don’t bruise. When will the pouches of dehydrated astronaut food come out for boiling? Or will our cooks soon resort to hidden caches of canned food stashed riverside by a supply raft that plies the river stealthily during the cover of night?

Fireside hors d’oeuvres on the river? Sure, if you are on a spring or fall trip. After all, who would dare dream of a roaring fire in July when it’s still 105 degrees after the sun sets? I’m sure appetizers during the summer are yummy in their own right, but last night’s baked brie with caramelized walnuts and fresh apple slices can only reach the heavenly delight of supreme comfort food while on a slightly chilly beach in autumn, warmed by a campfire, under the lofty cliffs of the Grand Canyon. Maybe someone paying tens of thousands of dollars for this experience could expect epicurean treats, but to me, having the good fortune to simply be here on the Colorado is already worth millions. What we paid for this trip was a bargain in light of how wealthy our memories are becoming. I could be fed a diet of twigs, sand, and coffee and still feel like royalty. This gastronomic dream-state must have been designed to enhance the experience of travel enchantment – as long as the passengers remain in perpetual bliss, they will forever be the greatest ambassadors of the Canyon, reminiscing of those days when from waking to falling off to sleep everything was perfect.

From a yummy breakfast at sunrise to the river and another great trail, we seamlessly transition through the moments as naturally as the day becomes night and then day again. The imperceptible fluctuation in the flow of air, earth, and river synchronizes with our internal clock, tuning us into the speed of nature. Old habits are temporarily ditched as new routines guide us. Down here, we are not getting ready for the day as much as we are preparing to be intently aware. Eyes open wide, the lungs breathe deeply, the ears are alert, and then it’s time to put the body back into action. All aboard!

The wooden oars slice into the calm river and exit with a “slip.” A delicate sound of “plink” is heard as water drops fall from the oar blade back into the Colorado. This auditory impression is impossible to capture with the written word, as verbal frailty foils the desire to adequately share the exact impression of the faint sound, though we hear it over and again. Listening with ears tuned to each detail, I find this sound akin to a marriage and separation of oar and water. Part of the uniqueness of this voice of the oar may lie in the spatial relationship only found here on the Colorado. The shape of the low-slung wooden and fiberglass dory, the distance of the hardwood oar, and the quiet on a calm stretch of river made more so by the heavy canyon walls weighted in silence, dampening sounds, all working to build this acoustic trinket of subtlety.

We glide along, passing mile 55. The oars touch the water and, for a second, appear to float on the surface tension. A long pause, and then into the river they sink, to be pulled by the oarsman, rowing us forward. Mile 56. Out of the water, the oar momentarily hangs in space with a drip, drip, drip. At mile 57, the dory is gliding downstream with us spellbound passengers, each drifting within. Mile 58 must have been there somewhere, too; likely that 59 slipped by similarly. Passing mile 60, we spring back to total awareness.

For here we are, where the Little Colorado River joins the really big Colorado at mile 61.5. Actors one and all, how else to describe our deceptive lack of drama upon our arrival? Who taught us this act of feigning subdued composure? Maybe it was conditioning for conformity? Was it a parent who told us not to run to the next ride at the amusement park? Or maybe it started back in high school when we were trying to convince ourselves of what was cool. Somewhere in our past, we lost the innocence we had when the sight of a birthday cake with candles flaming brought us to ear-piercing shrieks of joy. And you should know that I would surely be one of the first to raise an eyebrow of disapproval at the disturbance of nature’s solemn quiet, should the sounds of elation fill the air. At the same time, I hardly believe the rocks and river would care. So I scream a silent hoot and holler, jumping up and down inside, that this really is the Little Colorado.

The boatmen had anticipated its water to be a muddy, turbid flow due to the recent rains, which could have had it looking much like the larger river it was joining. Had that been the situation, flexibility would have played a hand in deciding that we would move on to points further south. But to our delight, the river is a beautiful opaque turquoise. At the confluence of the two rivers, a rippled border easily delineates the limestone-saturated Little Colorado from its chocolaty-red bigger brother. Toward the end of these rivers’ merger, when the combined waters pass into the main channel, evidence of this tributary is already lost.

In a couple of minutes, the rafts and dories are tied down, life jackets are secured, and our group collects, waiting for the boatmen to join us. Containing myself to the best of my ability, I stop short of breaking into a sprint to run ahead to see it all by myself, knowing that a minute later, the view will be shared with the others who follow. Four or five steps are all that I make before I have to stop to take closer examination of the water flowing over and adding to the travertine ledges the Little Colorado has built. Then, I take another few steps before gazing at the swirling stream of water descending through a pocket of carved rock, where the limestone solution’s various depths determine how clear or milky it appears. When the sun shines on deeper pools, the river gains luminosity as though lit from within. Red rock, white water, blue sky, chocolate river, tan sands, and green brush – who dreams this stuff up?

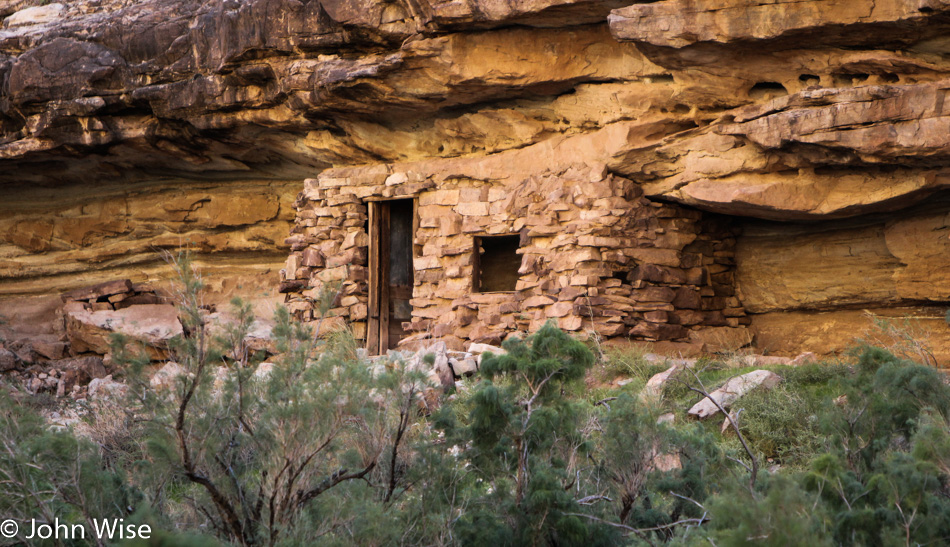

Here at “Life in the Grand Canyon 101,” this immersive class for living in the wild offers me the materials and experiences to become acquainted with nature on her terms. We lightly touch upon a multitude of potentialities that exist here, but the heavy subject-specific lessons exploring the fine details and depths of Canyon knowledge will have to be taken up after graduating from these 18 days. Our instructors walk a relatively short distance with us up the Little Colorado channel. The trail ends for us across from an old ruin of a house, said to have been built around 1889 by the miner and pioneer Ben Beamer. Ben placed his home right on top of a prehistoric Native American ruin that John Wesley Powell had identified two decades earlier. The story goes that the old miner lived down here for almost three years, never making contact with anyone else nor leaving the Canyon during that time. We gaze at the small dwelling and the Little Colorado until it is time for us to leave; what was closer to an hour feels like not much more than a few minutes. It only takes another second before the rear-view mirror on the dory loses sight of that limestone-saturated river. Goodbye, little brother, it’s time to become a man.

Not much further downstream, we are nearing the Hopi salt mines. A briny mixture is seeping from the cliff face that lines the river; dripping crusts of the white mineral collect and adorn the canyon wall. We keep our distance as we are reminded by the boatmen of our obligation while on the river to observe and respect the areas held sacred by Native Americans. The salt that forms here is collected by boys who have traveled the Salt Trail from Third Mesa on the Hopi Reservation to the river in a rite of passage.

The Canyon widens at our approach to the Unkar Delta, also known as Furnace Flats. Spring and fall are the times to stop here because, during summer, you will learn the true meaning of the term Furnace Flats, as life is baked right out of you. After getting a bite to eat for lunch, we depart for a hike. As is usual, we are going up, and as has happened before, the view expands, stretching far and wide. As also happened before, that part of my heart and mind used for sensing the spectacular opened up to points equally far and wide. I try to understand that at these junctures of physical, mental, spiritual, and aesthetic dilation, it is only natural that, as the eyes attempt to reach beyond their sockets, extra tears are necessary to ensure the eye remains moist and effective in relaying the unfolding beauty to the heart.

Petroglyphs, etchings on a boulder, an unknown language, a signage of direction, maybe a history for others, whatever these markings once meant, they are mostly indecipherable now. We can guess that the image of the antelope was an indicator that this stretch of trail is popular with these animals, giving hunters hope of finding a meal, a source of tools, and clothing in the area. The shapes, swirls, and designs, though, do not easily lend themselves to interpretation. Maybe because we can only speculate on their meaning, the ancient graffiti intrigues us into imagining there are hidden secrets locked into this primitive trail-side billboard. Wearing amateur anthropologist hats, we investigate the glyphs that I wish could speak to us, allowing insight into their missives. We continue our hike on this trail, leaving behind found mysteries to search for new ones.

Further up the easy trail, we approach Solstice ruin. We are in the Dox layer. The rock in this area is relatively soft, which explains why shortly after leaving the Little Colorado, the hard-edged riverside cliffs gave way to the more wide-open Furnace Flats. The softer rock erodes faster, producing hills with gently rounded surfaces. At the ruin, not much more than a short wall above the foundation remains standing. In its day, the neighbors might have envied this house, sitting on the hilltop with commanding views upriver and over to Comanche Point, 4,300 feet above the Colorado. A discarded metate lets us know that mesquite beans or corn was ground here as part of the local diet back when the owners of this dwelling called it home. Around the perimeter, hundreds, if not thousands, of pottery shards invite closer inspection. Various patterns and designs attest to the artist’s creative ability and, to my untrained eye, are reminders of pottery seen in Southern Colorado on the Ute reservation.

Standing at this long-abandoned dwelling, I attempt to bring together the extent of my knowledge of the Puebloan people. I want to envisage their trails and travels so that I might follow them east through canyons and desert, over the Hopi ancestral lands, and into those of the modern-day Navajo, where, on occasion, their journey could continue to ceremonies and festivals held in Chaco Canyon, over in what is now New Mexico. Did these Puebloan pilgrims walk through the Four Corners region, where various tribes such as Cliff Dwellers, Plains Indians, and other indigenous peoples from across the land might have crossed paths and enriched one another’s culture? Would one band of Native Americans trade pinyon nuts for some of that tissue-thin, blue corn piki bread made by the Hopi? Maybe plant dyes were on offer, or needed medicines exchanged? I don’t really want answers or the specifics, instead, I rather enjoy the conjecture of what might have been without the filter that suggests people throughout history are war-like, prone to violence and conquest. This potentially Pollyanna-ish delusion suits me fine. The daily routine and curiosity of someone on a trek of exploration, traveling without marauding ideas, only the desire to know for oneself what lies over the horizon and to learn who those people on that distant land are. These are the people whose eyes I want to look through. Who were their storytellers, and how was the history of their people shared with others, not of the same tribe? What songs and dances were enjoyed around a fire that may have accompanied celebratory feasting for good weather, healthy crops, and a peaceful life?

Who was born here in this crumbling abode? I can imagine their descendants walking the same earth as I do today. Are they constrained by a reservation where traditional ways and freedoms have all but disappeared? What sadness might an indigenous person feel, standing on the birthing ground of their ancestors, where ownership and rights of visitation are controlled by an occupying people? It is tragic that we must protect these historic treasures from those who would profit from their theft or those of low wit who might damage these relics for no other reason than their compulsion to flaunt their disrespect. Fortunately, our National Park Service has a good working relationship with our Native American neighbors, allowing those on ancestral journeys to follow in their fathers’ footsteps.

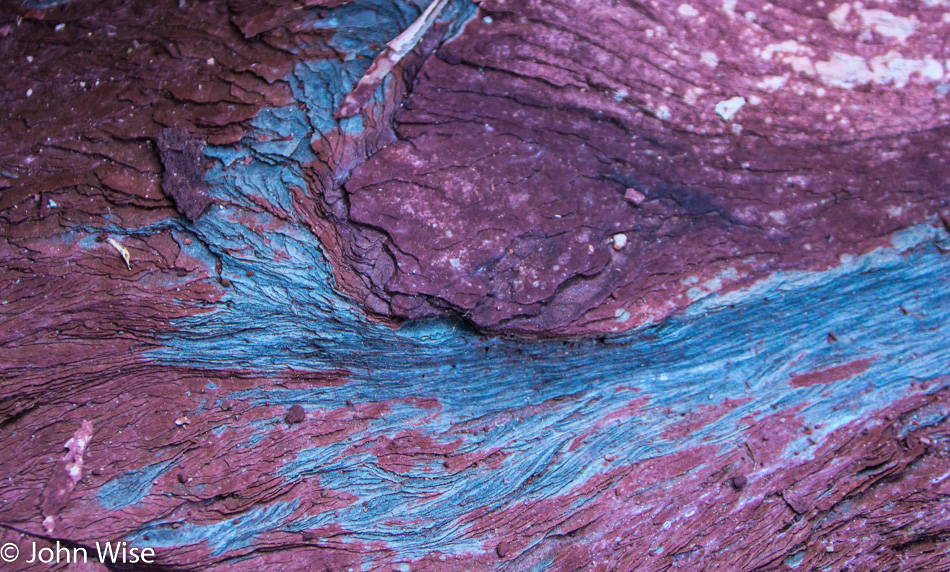

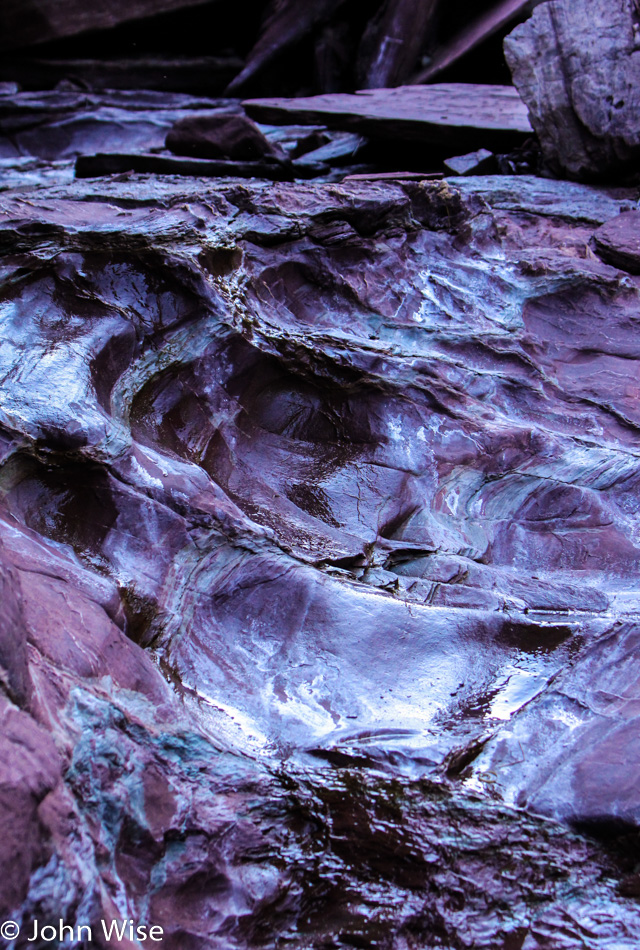

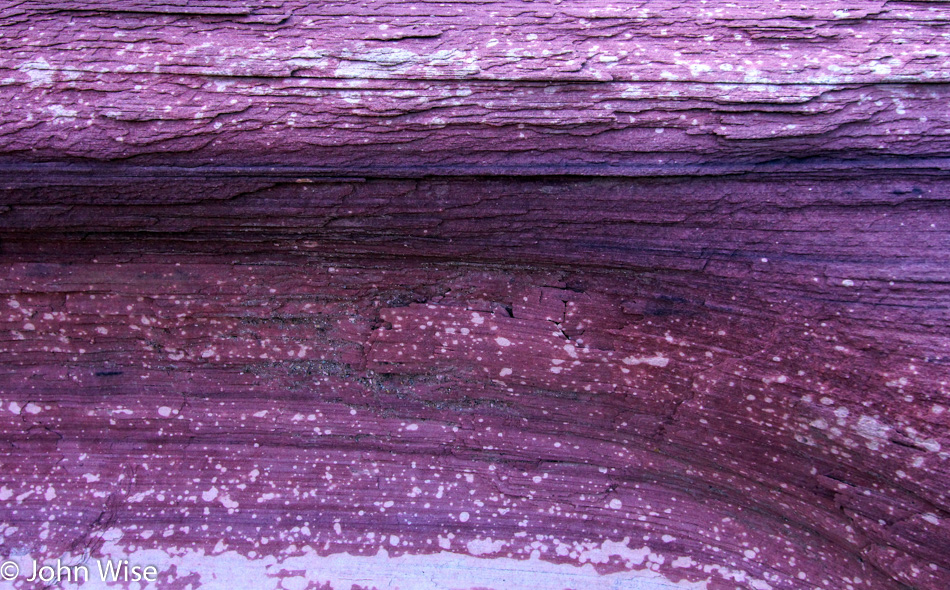

From this old home’s front yard and sweeping views, we move to explore the backyard. Contrasting those expansive vistas and distant horizons, the trail out back narrows with the line of sight, interrupted by a blizzard of rock that will soon surround us. Like snowdrifts made of multi-hued stone, the terrain undulates and disappears behind taller drifts of earth. The path is at times unseen; it is only the intuition, or previous trail memory, that guides the boatmen through this labyrinth. The walls are smooth in places, cragged in others; they are mottled rust with swirls of purple. Leeching salt crystals find a place to grow on protrusions; red stains drape over green rock, broken lava folds heave to form sharp edges, with pockets of empty space created by processes at work during an unwitnessed history long before modern humans arrived.

The various types of rock represent a multitude of minerals and composite materials, and with each comes just as many ways that it can erode. Where softer and harder rock were married millennia ago, the passage of time has weathered their relationship; thin ribs of hard rock stand like a skeleton above the recessing, softer sandstone. Overhangs form where harder upper layers stand in resistance to Mother Nature’s onslaught, but down below, its softer foundation is slowly washing away. Rainwater finds its way from high on the canyon rim, the surrounding areas, and various drainages to spill over cliffs and flow through gullies, scrubbing away loose sand and soil, depositing it in the Colorado somewhere below. The friction of this abrasive action shapes and polishes this tapestry of twisted form. Out of that chaos, the art of the planet emerges on a scale almost comprehensible.

It is as though the painter’s palette spilled over, and the primordial hand of nature laid down strokes to offer inspiration to a future Jackson Pollock. No matter my efforts, I will not find a method for merging myself into this stone canvas and disappearing into the beauty that paints this landscape. I can only try to share in the thousands of years of admiration from those who have visited this gallery dedicated to the monumental work of Earth art surrounding us.

Could Salvador Dali have found inspiration from the melting forms of travertine? Might Van Gogh recognize art imitating nature after looking at crumbling walls of chipped shale and fractured debris? Are there undiscovered motifs here only awaiting the creativity of a passerby to find their value? How do we know where and when our land transcends utility, elevating it to the sacred? If crude oil were found in the paint used for the eye of the Mona Lisa, would we gouge it out to operate a car for one more millisecond? Could we imagine melting down the mask of Tutankhamun to personally enrich ourselves? So why do these unseen corners become worthless to a city-bound society? How can others dream of damming a river to produce a bit of electricity or drilling into a canyon, filling it with noise and the clutter of machinery in order to extract more natural gas or uranium, when we now have the ability to harvest our energy needs from the sun and wind?

We can work smarter to harness alternative methods to power our world. They may not be easy or expedient, but we can learn to do without some convenience, as humankind will never build a Grand Canyon. Man will not learn how to create a mile-deep gorge, hundreds of miles long, that can bring us to tears of joy while standing before such resplendent sublimity. When will we stop our sprawl and outward expansion? Look around the Grand Canyon; it is eroding, disappearing. While not in our lifetimes or our immediate future generations, the Canyon is going away. When it is gone, only photos and stories will tell of what was lost, hopefully not due to faults of our own. The same will not be said for what man intentionally destroys in his quest for domination and his petty sense of ownership.

Our time to experience this side canyon is over. We’ll leave it just the way we found it. Should you visit this exact place, you may not see precisely the things we have seen, not because we altered anything, we leave that to the forces alive and at work crafting these sights. An earthquake could rattle through, a boulder or a cliff face might fall, or a flood of biblical proportions could roll over hill and dale, forever burying a place everyone’s senses should have had the opportunity to enjoy at least once. For now, I depart but not without a manifest full of glorious memories from just one more of the many unnamed and anonymous side canyons hidden here in the Grand Canyon.

From our mile-and-a-half-per-hour trail pace, we return to rowing downriver, clipping along at better than three miles per hour and flying over Tanner Rapid shortly before sunset as we sprint into the end of the day to prepare our evening shelter at Cardenas Camp – mile 71. And a race it has been. In these five days, we covered 71 miles of the Colorado, clocking in at a whopping average of 14 miles per day. There must certainly be a kind of magic at work within the Canyon regarding our perception of time versus distance. Pardon the math and numbers as I try to reconcile my memories of time spent on the river and just how we will have ultimately passed from mile zero through mile 225 at Diamond Creek – our exit. We have been on the river only three to five hours per day. If I calculate that we average four hours per day on the river, we will amass approximately 72 total river hours over the distance of 18 days. Dividing the distance traveled by these hours, our speed figures out to a shade over three miles per hour. But with the river flowing at three miles per hour and rapids crashing along significantly faster than that, it leaves the impression we did nothing more than float downstream. This is not a complaint by any means; it is the strange recognition that, while my memory tells me the boatmen worked hard to row us down the Colorado, delivering us to incredible adventure, I am now beginning to wonder whether their efforts may have in reality been used to slow our progress. Can I find clarity of memory to see if our dories moved with the current, faster than the current, or were we being passed by the flowing waters?

This then begs the question, what secrets of human perception do these boatmen know and utilize to their mystical advantage? To a growing list of words describing the boatmen, including guide, cook, and teacher, must I now include the profession of magician? How else does one explain that we eat three meals a day, ply the Colorado running whitewater with fierce rapids, hike, explore ruins and side canyons, investigate the fossil record, listen to stories and the song of guitar, mandolin, and campfire with all of this fitting into the shortened days of fall leading into winter? Only an illusionist could fool the perception into thinking it has seen more or less than it really has.

So how do days without end, delivering experiences that should require a week, a month, or even a year, come to a close? This one does so under the majestic light of a rising moon, illuminating the palisades off in the distance. In camp, a dwindling fire and an even thinner crowd brave the cool night for another moment of it all. Raft pilot Ashley Brown, who has been quiet until now, takes up the proverbial podium. Seated near the fire, she reads from John Wesley Powell’s account of his historic first journey down the Colorado in 1869. With a world and 141 years between us, I listen with half an ear while taking notes about my first trip, following in his larger-than-life footsteps. He was exploring the wilds of nature; I exploring the wilds of the mind.

–From my book titled: Stay In The Magic – A Voyage Into The Beauty Of The Grand Canyon about our journey down the Colorado back in late 2010.