Sleep is never easy after such a long flight, but exhaustion helped me stay in bed for a bit more than six hours. After a quick chat with Caroline, I was in the shower and soon checking out of the hotel. The Ramada sits on the corner of Kaiserstraße and Weserstraße in the former red-light district. I walked over to the Hauptbahnhof to check in regarding my online ticket to Berlin; things were easy enough, so I went for a croissant and a coffee along with the wifi connection so I could post yesterday’s musings.

In a few minutes I’ll head over to the track I need to be to board the I.C.E. to Berlin.

The train arrives with a minute to spare and we end up leaving a couple of minutes late. No big deal, as minutes later, we are already traveling smoothly and quietly at 150km/h or 93mph. No clickety-clack of the tracks, no loud kids, matter of fact, I could hear the guy a row ahead and on the right side of the train chewing his food.

It’s a beautiful blue sky day with some billowy clouds dotting the sky. While it’s a brisk 45 degrees outside, the signs of spring are abundant. The trees are sporting fluorescent green new growth and are casting long shadows that fall on the train windows. Outside of those windows, the landscape changes from small farms to villages, and in between are tree-lined corridors. Underpasses and random buildings are decorated with graffiti next to the tracks, though the grounds are spotless.

An hour east and the sky has grown heavy. The sun still shines through breaks in the clouds, but rain could easily be a part of my day. The occasional windmill has been spotted in addition to small solar panel farms. The train is a bit too warm for my liking, though most everyone else here still has a sweater on or at least a scarf, while jackets are stowed overhead.

Back in the 1990s, when I first rode an I.C.E., there were very few cell phones on board, and not a person talked on them while traveling. Today, the ringtones pierce the quiet, and just as in America, there are those people who have to stare at the screen for a moment to determine what to do next instead of silencing the ringer or simply answering it. I’ve not seen another person looking out upon the landscape; maybe they’ve made this journey once too many times, and it’s all boring for them. From my view, I recognize how little of Germany I’ve actually seen.

The second class is a zoo. The gauntlet of inconsiderate kids being kids clogs the aisle, but it is the only path that brings me to the restaurant car to get a bottle of water, so I must run it. Is first class more civilized, or are those of us up here more demanding of civility? I do have a complaint now that I’ve visited the other cars: it’s significantly warmer in my car, uncomfortably so.

We stopped in Bebra, but the announcement was in garbled German, so I couldn’t follow. Nobody but some Deutsche Bahn workers got off the train; no one got on. In this small town of around 15,000 are over a dozen churches. The name is a shortened form of Biberaho or Village on the Beaver River. Upon leaving the small train station I am now traveling forward where for the previous hour and a half I was seated going backward.

It’s 11:20, and we’ve just pulled into Erfurt train station, which, a week from now, I’ll be returning for a few days before continuing my travels eastward. Prior to leaving the States, I was nervous about my rail travel as I feel I grow rusty between visits to Europe. Now that I’m here, I remember the dependability and ease of traveling by train. I tentatively penciled in a couple of side trips but was uncertain if I’d actually make them as maybe the train wouldn’t be on time or what have you; instead, I’m reminded how convenient this all is.

On this leg of the trip to Berlin, we finally hit 300km/h or 186mph. There’s a bit more noise from the wheels below the train, and there’s a sharper vibration, but it’s still very quiet and easy enough to walk the aisle. Passing another train can be a shock, and the pressure in the tunnel we are traveling through makes my ears pop. While a flight would have been a fraction of the time, it would not have been so elegant nor offered so much to see, such as the many fields of rape that are in full glorious yellow bloom.

The next stop is Halle on the Saale River. This was an early Celtic settlement with the name Halle reflecting the word Halen, which is the Brythonic (Welsh/Breton) word for salt. The river Saale is from the Germanic word for salt, too, so as you might have guessed, this region was important for salt harvesting. Its salt history extends back to 2,300 BC, while much more recently, the town gave the world the composer George Frideric Händel. Our final stop will be Berlin.

I try not to panic much with the anxiety of finding the next place, and so far, things are working out great. My Airbnb is only about 15 minutes by foot from the train station at Schöneweide. I was starving by the time I dropped things off and had my keys. I was going to head back into Mitte (city center), but a Kebab shop looked good enough for how late it was, so out of convenience and since I do like döner, I made do. The thing was only 5 euros and was giant. On to the city.

This will be my stop-and-start point for the next week in getting into Berlin proper. I’m in former East Germany, for what it’s worth.

Might as well start at a landmark so I have something to focus on later and know where to head back to reconnect with the S9 train I’m exiting. I’m at Alexanderplatz, walking in the direction of other landmark buildings that can also act as proverbial breadcrumbs.

Wow, such a nice touristy site I just learned about; this is the Neptune Statue, built back in 1891. The four women seated around the god of the sea represent the four major rivers of Prussia, as Germany was known before 1871; they were the Elbe, Rhine, Vistula, and Oder.

With all the warnings on this sign about various concerns while using the park, they forgot to add that stickers are forbidden.

Sadly, this church was closed as it was unsafe for visitation. Its relics have been removed until a determination is made on what to do with the facility. Maybe I’ll find another church later.

Another church wasn’t too far away from this one called St. Hedwig’s Cathedral, but wouldn’t you know that it is closed for renovations?

From arriving at the main station to trekking out to my stop at Schöneweide on the S9 train line and my subsequent return via train to Alexanderplatz, I’ve gotten my first minor impression of a unified Berlin, and it is fraught with mixed emotions. I’m in a Capital city that I feel is trying but failing to create a national identity. Germany is approaching 20 years since the fall of the wall and reunification. I was living in Frankfurt back then, was newly in love with Caroline, the computer age was blossoming, and techno music was starting to make Europe dance.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Eastern Bloc was toppled like proverbial dominoes under the strain of authoritarianism. From those ashes, optimism sprung to life while simultaneously complexity was on the march with broad implications for the working classes.

Prior to the modern post-industrial age, the common person found solace and sought relief in god as people turned to the church. In the age of information, our careers have become the church, and god is the money we use to pay our bills. As humanity flocked to consumerism, it looked for salvation in the ability to purchase happiness and find its identity in what it had newly acquired. What purpose was this power-to-shop going to offer?

Once the novelty of buying all the upgrades wore off, the newly disaffected addict of all that was new was left wondering, “What’s next?” The obvious answer was, “Another upgrade.”

While many are satisfied with this cycle, those who were being marginalized by expanding technology and a flood of immigrants began to realize that they were made redundant without a safety net of renewed purpose. The secular state was certainly not going to tell these displaced people to look to god for help, while it knew well enough that jobs for that sector of labor were never to return.

It is my summation that governments and business leaders hoped for the tech industries to offer a solution. The problem here is that with each step forward in convenience, the underlying architecture of work becomes more difficult to train for. Hundreds of millions and, in some emerging cases, billions of people are being connected via networked services through a myriad of apps. New solutions and conveniences must be invented continuously. We no longer operate with long-term maintenance in mind, where repetition is a primary career; we are in constant need of people who can reinvent the future.

Turtles do not invent anything, but they do know how to survive. They pull their head back into their shell and wait for the danger to pass. Through the first part of the 21st century, as progress moved at a breakneck pace, many people pulled back to see how things would play out, but what was happening was a global shift in geopolitical resources and the redistribution of the labor pool. The turtle was made irrelevant while it waited too long to figure out how to adapt.

Humanity is, in some ways, like water: it adapts to obstacles and continues to flow through blockages. At times, it has to build up pressure until it finds a weakness to exploit a new path. From this point, it can explode forward to alter the landscape.

There’s a danger to this type of increasing pressure in that humanity is people and not water; people turn to an authority that can marshal the pressure to break out of old paradigms and find new ways, even when the new ways are radically different than the past. There are signs of conflict all around Europe, shadows of wars, and uncertainty. With the fall of the Soviet Empire, the self-defeating Brexit, and America’s potential turn towards isolationism and maybe even fascism, the blueprint of upheaval may be exposed.

I’m sitting in the Berlin Dom; well I was sitting in the Dom until I was kicked out early for a service that required everyone to leave who was not on hand for the sermon.

Awareness of the role that these places of worship played in the past doesn’t help us define a purpose or general function for our species. Today, there are more people visiting cathedrals as tourists with a desire to take selfies instead of finding solace or giving alms.

I believe Germany’s government foresaw this identity crisis and lept at trying to quickly create an inclusive European identity, but British and American moves to conservative politics might yet undermine a positive evolutionary path where continuing peace would be allowed to thrive.

Should nationalist-driven fear of change and the unknown take deeper root among the less fortunate and those being catapulted into the margins, we, the people of Earth, could witness humanity take two or three solid steps back.

My first impressions here in Berlin are that people are generally uncertain about far too many things. On a recent visit to Hungary and the regime of Viktor Orbán, the people seemed fairly positive; then again they already have a strong-arm anti-foreigner zealot at the helm. I hate to imagine the return of another ultra-conservative charismatic leader in central Europe who rallies large swathes of the population to celebrate white exceptionalism.

Over the course of my stay in Germany, I’ll be taking a hard look at the question of whether multiculturalism is dying.

My original plan had me visiting museums tomorrow; I’m reconsidering this idea as I feel I need to go and see where people actually live in Berlin.

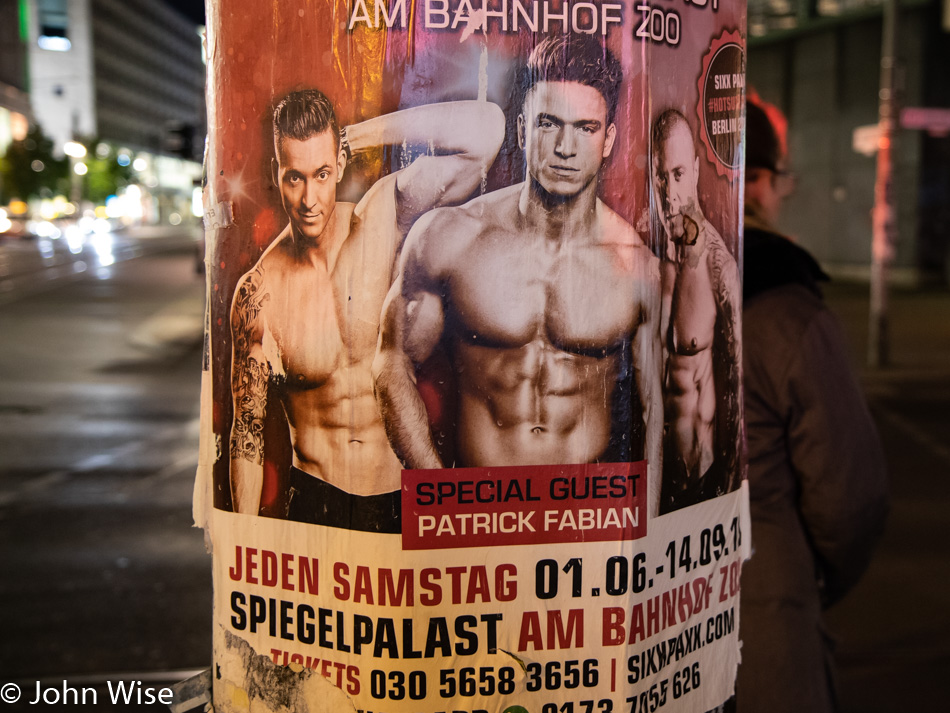

Jetlag is playing me like an evil twin pretending to be me, just different enough that someone who knows me will sense that something is off. Waves of minor incoherence sweep in, but the momentum of traveling is trying to carry me through. There’s a kind of shame of being on vacation and only barely being present due to my exhaustion, a bit like wasting time. I’ve stayed out here in the city center as long as I can, trying to prop myself up with coffee, but it’s now time to skip the hot dude show and head to my room in East Berlin.