Blinking lights, knobs, shiny jacks, switches, buttons, tiny print, crazy characters, screens, and storage are just some of the parts of what makes a Eurorack synthesizer. Nearly every day, I turn on the machine next to me and am simultaneously dazzled and baffled by its beauty and complexity. Adding stuff to it becomes an obsession while learning its myriad functions can be mind-numbingly frustrating in part due to a certain obtuseness inherent in the beast and, on the other hand, because the larger the system gets, the more difficult it is to truly know all of its parts.

So, while I stand in awe of the synthesizer I’ve assembled from dozens of modules emanating from creators from around the planet, I also study the undeniable visual appeal of this contraption. I’m certain I’ve made decisions on acquisitions that were probably influenced to a greater degree by the aesthetics of a device rather than what its ultimate purpose might end up being. I justify this by convincing myself that regardless of why it is here, I am now committed to finding the angle to make the purchase integral to my larger goal.

This blog entry, as much as possible, will look at but a few of the user interfaces I play with every day. Not the overall design or the totality of functionality that a particular module might be capable of, but a peek into the surface of this synthesizer.

Featured above is a device that is not mounted within my rack, such as the modules that will follow. It is a recent buy that I luckily found on the used market as they are a rare find these days. You are looking between two knobs of the Monome Arc. This four-knob precision interface does require a module to be mounted in the rack called an Ansible, and with it, I can manipulate control voltages and gates that communicate with other modules within my configuration. This also brings me to Monome, the company that makes the Arc and Ansible, and how they have altered how we use surfaces and data to tease out of the machine the sound and functionality we are trying to discover. Monome also makes another control surface called Grid, which is now able to interact with the Teletype, also a Monome design By connecting a computer keyboard to the Teletype (not pictured) we are able to use a scripting language to “talk” with other modules within our system in ways that had not been previously possible. The point here is not to sell you on Monome or write sales copy endorsing their brand; it is to point out that the systems around these synthesizers are still evolving, and while the ubiquitous knobs and jacks are ever-present, how we manipulate these elements is open to interpretation.

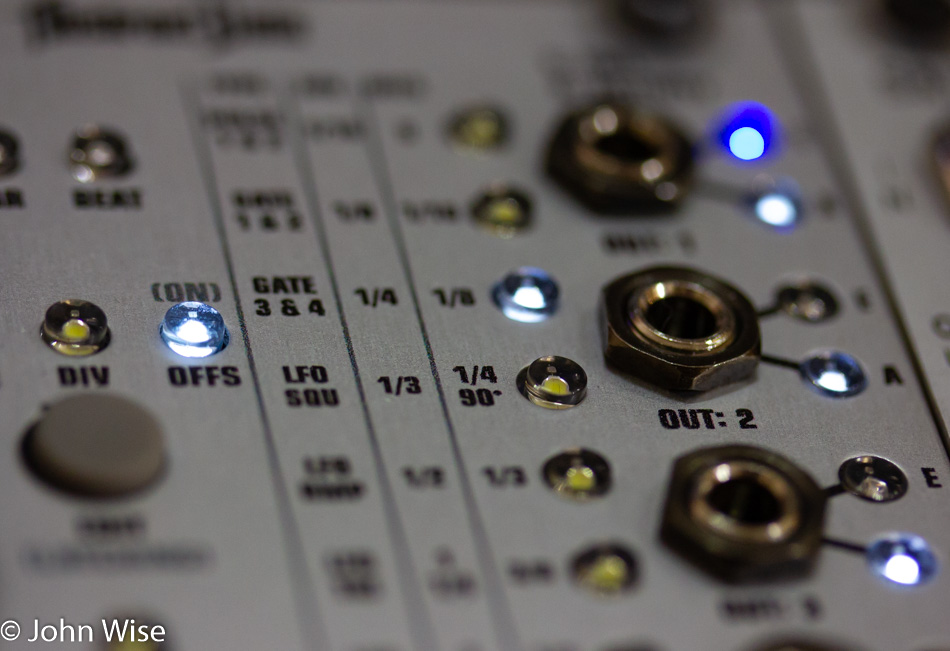

The feedback loop of information is presented in many ways to the Eurorack user, such as using lights, as seen on Pamela’s New Workout from ALM. Lights can be color or brightness-coded, and some offer feedback to the user based on how fast or slow they blink. These visual clues allow the user to gain an understanding at a glance, for example, whether the voltage leaving a jack is negative or positive, which might be represented by a red or green light. If a light is dim the voltage might be low and brighter when the voltage is running high. The blinking frequency might represent clock pulses that are determining tempo or could be offering info about how long a gate is open.

More and more modules, such as this Piston Honda MK3 from Industrial Music Electronics, are offering SD Card access. While function varies between manufacturers, we are able to better interact with device information, the ability to update firmware, save presets, or load custom sound files. Often this storage gives the user greater options and ease of use that wasn’t previously available; then again, when all synthesizer modules were analog, and musicians only needed to patch inputs and outputs while adjusting knobs, that wouldn’t have been an issue. With the rise of digital modules and greater complexity, there are those who may prefer simpler times, but there is a burgeoning world of enthusiasts embracing the options where a module’s functions may not be set in stone.

As new modules become available, it can become apparent to users that the functionality of a device and, hence, how information is exchanged can be altered from what the original developer had intended. At that point, the would-be creator will have to embark on a learning journey that will take them from the circuit design of the new complementary module to the distributors of buttons, knobs, and jacks, along with PCB manufacturers and the overall specifications of the Eurorack standard itself. Knobs and the pots they are mounted on all have a particular look and feel, and it is up to the artist to balance their critical engineering minds on how something will ultimately be presented to the consumer. Knobs that are difficult to use, too tight to easily turn, or too loose that, when bumped, send a signal out of control have to be evaluated regarding their utility to the user. The knobs of the modules above belong to the TXi, which is a companion module to the Teletype and created by BPCMusic. Once Brendon Cassidy, who is the founder of BPCMusic, saw that using a rarely used protocol called i2c that the Monome Teletype takes advantage of, he could create a module that not only offers interface options from the knobs and jacks upfront but could also use a backchannel found in i2c to talk with the Teletype and extend an ecosystem of communication that would make the sum of the parts much more valuable. In this sense he not only allows us, users, to interact with the data moving between patch cables, but he’s also pushing things further by taking advantage of subsurface data transference.

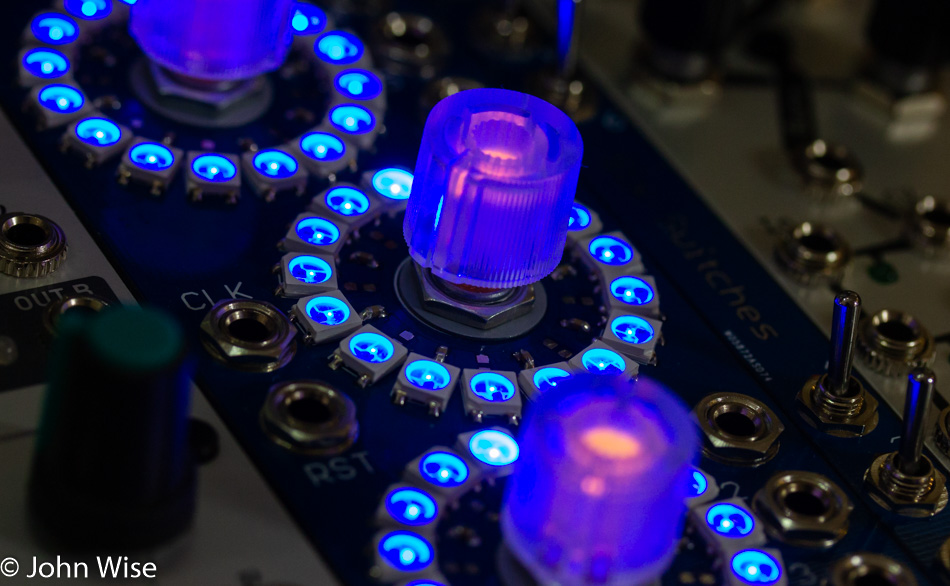

How to shape the complex into easily readable visual information was the angle that Vladimir Pantelic of VPME over in Germany was exploring. Back in 2004, Godfried Toussaint discovered Euclidean rhythm and wrote a paper that described the division of beats to the most equidistant distribution possible and that, with modifications, you could bring up almost all of the important music rhythms celebrated around the globe. What Vladimir brought to this are light-emitting rings where different colors will show the musician which steps or beats are active in a module called Euclidean Circles. This module allows the user to dial in various rhythms and then determine the best distribution following the Euclidean formula. Also, while there are just three rings, there are, in fact, six possible outputs with the push of a button, the user can change the color of the knobs and rings, which then denotes the second channel of three outputs. So here we see a very complex music theory that was only recently discovered and offered to the music-creating public in a relatively easy-to-use device that, while still somewhat complex, does a great job of bringing the data of operations to the surface where a quick glance can show the user a wealth of information.

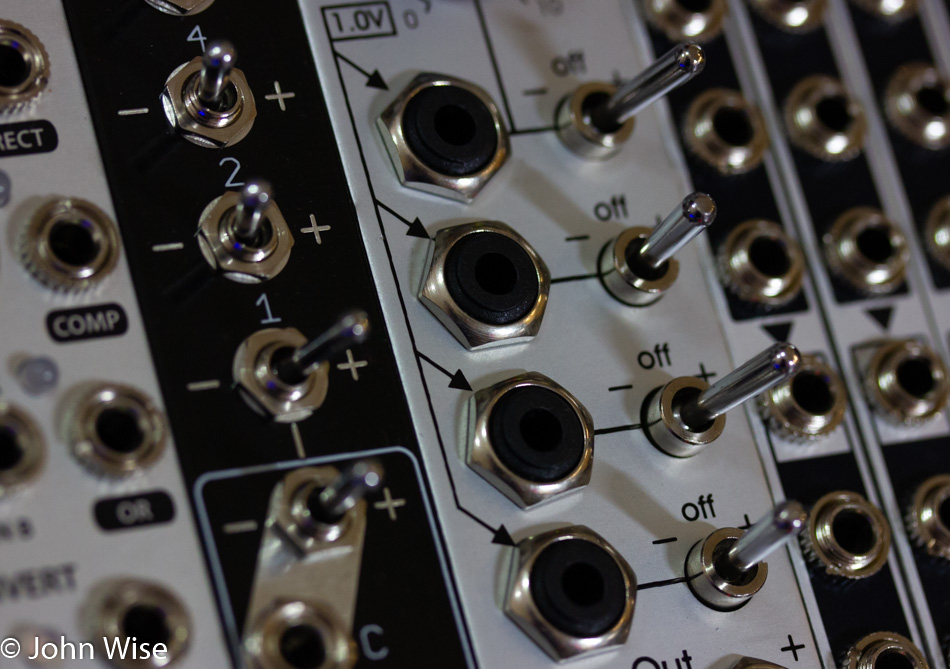

Though some would argue that a mere two or three modules can represent insurmountable complexity that stifles their ability to make music while they are bogged down just trying to understand signal flow, there are many clues on the face plates themselves that offer information for deciphering their utility. Take the Doepfer Precision Adder pictured here (by the way, to the left of the Doepfer is a variation of the Precision Adder created by Vladimir mentioned above) the arrows on the panel show the cascading effect of the voltage while the switches show the user negative, neutral (off) or positive inclusion of the voltage that enters the module above and exits below after being added to, subtracted from, or not affected at all.

In the world of flowing audio and voltage signals, there are seemingly infinite worlds of possibilities to alter this potential cyclone of swirling electricity and sound. Variations of signals at times require minute changes to what is coming into the module. Switches might allow for coarse or fine-tuning of what the knobs will be modulating. Other signals that can have an impact on the overall sound or voltage might have color-coded knobs that are tied to sliders or will have lines drawn on the panel pointing to something else that it is helping modulate. By having this wide variety of knob shapes, switch types, sliders, screens, and button types, the users can hone in after memorizing some of the color and module orientation specifics and allow them to build muscle memory of what does what and with a quick glance move to selecting the modulation source that best suits their need. Xaoc Devices out of Poland makes this Belgrad Filter using the red and black motif as a branding theme with modules that often have a design sense of being from a previous industrial age.

With the advent of digital modules not only did we get SD Cards for extending our storage capability, but we also started getting display screens. While musicians had an approximate idea of what value a slider or knob was delivering in the days of purely analog gear, in this age where fractions of voltages dictate whether a note is a C2 or C# in the same key, having precise display values is invaluable. Here the layout of LEDs, buttons, and knobs have been strategically laid out in consideration of how much information the hand might otherwise obscure. With a lesser design that does not take into account the importance of being able to easily see and understand what the musician is affecting, a poor user experience can ruin the potential popularity of the creator’s invention.

Consider that these modules in Eurorack are only 128.5mm in height or about 5 inches, so there is a limited amount of vertical space to place controls and feedback information. If modules spread out and get wider, that can impact the number of modules the user is able to effectively have in front of them and could reduce some of the utility. The module above is the ER-101 Indexed Quad Sequencer from Orthogonal Devices in Japan. Brian Clarkson is the creator and sole proprietor of this amazing, compact, and well-thought-out design. For this level of complexity and sophistication, the user can expect to pay a premium, and that’s only when the modules are actually available from this one-man show. Reading Brian’s forum on his website can be incredibly insightful as he has discussed design and layout considerations that have influenced him. Not only that, he is in an active conversation with his community of users, talking about functionality and how to improve operations from a technical viewpoint, but also the flow of information that moves through his modules.

Lights and columns are other methods of conveying pertinent information regarding what data and choices are about to influence the signal flow. Choosing the ticks, triggers, and modulations of a range of frequencies and voltages that will blend seamlessly into a piece of music is a complex undertaking when one desires to use electricity as the basis for this creation.

Analog percussion as found in drums from the real world, were likely the first instruments to be used by humans and their interface was simple in that we would strike the drum or wood with hand or object and the resulting sound was our immediate feedback loop. To create an electronic drum that keeps time and plays in a complementary fashion with the rise and fall of sequenced and moving notes is quite the quantum leap when we look at it objectively. For the sake of compact systems, there’s been a trend to make utility modules that feature many functions that would otherwise require just as many individual modules. With the Abstract Data Octocontroller, there are eight major functions that are chosen with a series of knob turns where corresponding light signals will indicate the user’s choice of function and the parameters that can be chosen for a particular algorithm. In addition, there are a few buttons that offer some alternative choices to the basic operations.

To ensure your module stands out and can be identified quickly, adding things like yellow-capped knobs and red plastic-coated switches can speed the learning process.

This is but a tiny section of more than seven rows of modules that I own. As you can see from even this small cross-section there is the potential for an incredible number of jacks, knobs, buttons, switches, and screens. That the musicians most efficiently get to their objective while hopefully stumbling upon some happy accidents along the way is imperative. Matter of fact this idea of “Happy accidents” is probably better described by either the term generative music or “The Krell Patch.”

What is a Krell Patch? Back in 1956, the movie Forbidden Planet had a unique soundtrack that featured “Ancient Music” in the form of the Krell song. These are the days before synthesizers, and the composers Bebe and Louis Barron were only supposed to make weird alien sound effects. Instead, they ended up scoring the film and creating the first electronic music soundtrack. Then, years later, Todd Barton came along and experimented by building a patch on the Buchla modular synthesizer that should imitate the Krell song, and the Krell Patch was born. Modules that can shift timings and voltages in random but automated ways allow the performer to set the initial stage to cascade forward and backward to trigger events within the synthesizer that go beyond the logical progression of events that we typically expect in music. To that end, the Telephone Game from Snazzy FX with the blue knobs here is just such a device that creates new rhythms from input signals where the blue knobs influence how the new signal leaves the module to affect other modules further along in the rack. So again, we have a device that, while complex to use in its own right, offers a relatively simple user interface that masks some of the difficulty while allowing the artist to tend to other performance elements.

Regarding generative music, while Brian Eno is credited with coining the term describing an ever-changing sound created by a system, I feel it largely ignores the history of aleatoric music, as lectured about in the early 1950s by Werner Meyer-Eppler. There are other examples of chance music creation dating back to the 15th century right up to Karlheinz Stockhausen in the late ’50s creating these types of compositions. We should then also give a nod to Pierre Schaeffer, who in the 1940s gave us musique concrète using preexisting sounds to play an important role in breaking down preconceived notions of music. Now add Don Buchla to the mix, whose System 100 in 1966 certainly was a milestone by breaking out of the rules of structure that Bob Moog was mostly following with his first synthesizers. The larger point I’m trying to make is that the “system” of generative music was an evolutionary mechanical and intellectual process that has had many important contributors and theories that were added to the mix before it was able to start becoming what we might think we know about it today.

Timing and how we control the ticks that drive the entire system is one of the first considerations we need to make. While the tempo may be best decided upon by listening to the beat of a drum, it is what happens after that trigger to the drum that is going to have a great influence on the rest of the composition. Again, we can look at chaos and randomness to drive things forward, or what is more likely for the majority of musicians is that they will want a precise set of timings to work with that maintain a sync between the various modules. While we can dial in a precise tempo, such as 120bpm, via a screen on Pamela’s New Workout mentioned earlier, we may also choose to use a square wave from our LFO to drive the clock, and if we put that signal into a clock divider, we can mathematically create beat-accurate impulses that stay in time with the overall tempo.

In an analog world before displays, we used fixed output jacks that were hardcoded to particular divisions or multiplications if what we wanted were faster tempos for particular modules. A jack without a dynamic indicator would never give the user a precise visual clue as to when the output that was chosen to hit the snares was being triggered. You could hear it, but imagine you could look down at the blinking lights and see that the fourth jack from the bottom has a speed that you feel will best fit a particular sound, and so you patch that signal. Having viable visual information allows us to make judgments not just by ear but by the eye as well. This dual-purpose clock divider and multiplier is the Tik Tok from Animodule; Jesse McCreadie makes them; you should check out his modules. (That’s his tag line)

There are probably very few people on Earth who will ever remember all the functions of the various parts on a large system with over 1000 jacks and a similar number of knobs and buttons. If we are lucky, there is clear and large enough text that highlights the value of a knob or what a slider is responsible for. Some module makers decide to go the obtuse route and use funky font types that some may find difficult to read. Or the user manual is a poetic license of hints, or was never considered by anyone besides the engineer who wrote it? This issue of non-viable data about a module or less than clear guidelines on the module itself can act as a hindrance to the user finding the kind of utility with a module that can lend it great value. This particular module above is known as the Three Sisters from Whimsical Raps and has great information on the panel to determine which button does what, but the creator has decided to use non-standard descriptions at times that leave the user wondering what Air, Barrel, This, That, and Survey are used for. In addition, the creator of these modules has come under fire for writing prose in his user manuals that some claim is impenetrable, while others delight in the challenge of deciphering the puzzle. I’m in the latter camp.

Sliders offer yet another means to alter the flow of information, while a nearly useless manual does nothing to explain the markings above the jacks, but hey, this has to be part of the challenge of using something that is already so incredibly difficult anyway. Mark Verbos and his modules take great inspiration from the Buchla series of modules, and it shows.

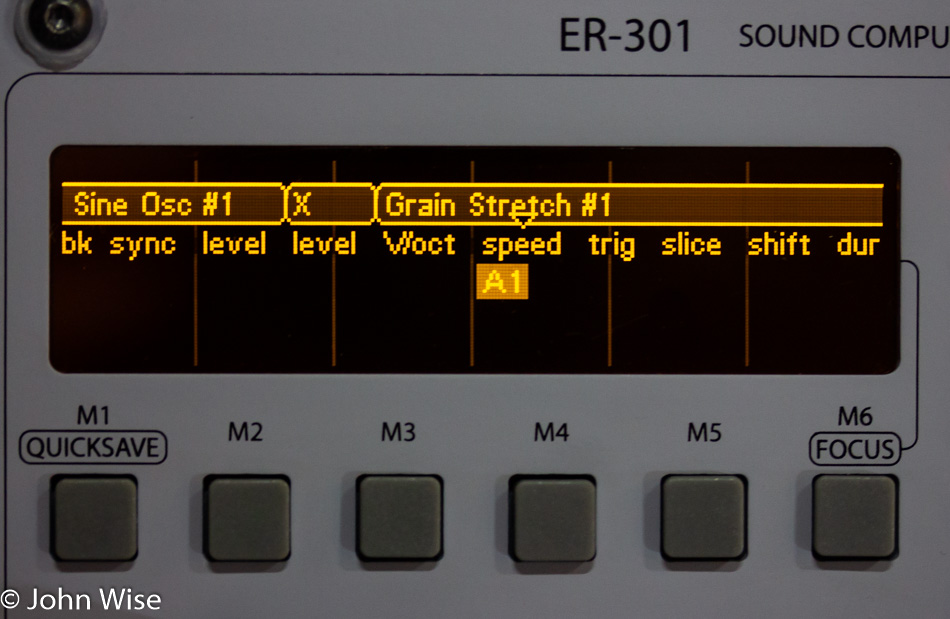

Screens. We don’t have touch screens yet, but the proliferation of screens appears to be gaining acceptance. This is Brian Clarkson again with his Orthogonal Devices ER-301 Sound Computer. With a fairly minimal physical interface driven primarily by a single large knob, this larger module is capable of things that extend far beyond the typical Eurorack device. Things can get deep here, as it is possible to assemble a complete synthesizer voice inside this module. Matter of fact you can create four mono or two stereo voices here and even add effects such as reverb and delay to your signal. I originally bought this for its sampling capabilities, but with feedback from the community and watching Brian’s design and coding plans evolve this device, he is changing the way we are able to relate to the incredible volume of data this sound computer is able to generate and manipulate. Not only do two screens feed our ability to interpret data, but we can also now connect the ER-301 to the Monome Teletype and Grid ecosystem, where we can extend the limitation of the ER-301 front panel ins and outs to having 100 triggers and 100 control voltages being manipulated by scripts in the background.

The interface and data we get from our synthesizers are going to change. I foresee the day when the touch screens from smartphones will move into our modules, and voice activation will set things in motion. Artificial Intelligence will analyze our signal flows and start to recognize patterns we cannot see and tell us how fluctuations in voltages could produce subtleties we may never discover while modulating knobs with limited amounts of granularity to change signals. Vision systems should be integrated for sampling light and the person’s movement and shape in front of the synth for generating random signals and influencing movement in algorithms to extend the aleatoric possibilities.

There are already great strides being made by the likes of Expert Sleepers where interfaces for MPE devices and old joysticks can interface with our modules. Landscape.fm creates fun interfaces for touch control, and his upcoming Human Controlled Tape Transport (HC-TT) will take old tech found in the cassette tape and allow the user to play audio to their Eurorack setup with the added character of noise and warble. Looking towards old meets new, Jesse McCreadie (Animodule) lent me a hand by converting an old telegraph key into a switch with 1/8-inch jacks so I could interface this nearly 200-year-old technology with my very modern Eurorack synth. These methods that explore the world of interfacing old and new are the springboards of innovation and experimentation where engineers learn the skills that will let them propel their discoveries into ever more complex designs that will surely challenge our ability to relate to the myriad data emerging from a tiny little metal jack.