How often have you woken up in commercial lodgings and been enchanted by the light that was illuminating your environment? From tents pitched along rivers or in forests to a cave on a cliffside in New Mexico, yurts on the rocky Oregon coast, and now this farmhouse in the Austrian countryside, they have all allowed Caroline and I to start the day with a flash of inspiration that unequivocally assures us just how lucky we are to see these things firsthand.

Sitting in the garden of this 400-year-old farmhouse here in Hörsching, the sky has fluffy little pillows of clouds to my right and blue skies to the left. Birds of at least a half dozen sorts are all around us. The sheep are yet to stir, but with this being a farm and all, the flies are doing their best to be slightly pesky.

Caroline made us coffee and is working on a pair of socks for me while I try my best to do some writing. Before stepping outside, I was filling in some blanks regarding day 9 of this adventure, which was the day we traveled from Verona to Gorizia via Padua, but as we moved outside, I found myself distracted by the sounds, light, smell of flowers, and slight breeze to such a degree that writing about an 800-year old church became impossible.

Hunger will propel us to leave sooner rather than later, though I’ll go ahead and repeat that a short stay here of just overnight does not do this place justice.

Over the past few days, Caroline was slowly changing our plans, and last night, on the way from Vienna, they were cemented; instead of going to the salt mine, we will deviate from our path and visit the village of Haslach an der Mühl whose claim to fame is an exceptional textile center and weaving museum. The funny thing is that this salt mine was one of the prime reasons for us coming to Austria in the first place. I’d like to say it will be easy enough for us to return someday for that or another salt mine, but we know that we also want to visit the Scottish Highlands, the Scandinavian countries, Iceland, and rural France. Even if we were to do a European-centric trip roughly every other year, this takes me to about 65 years old, where I’m guessing I might be slowing down from walking an average of about 10 miles (16 km) a day as we have on this trip and that travel will be different.

The owner of the farm, with a child that sounds to be about two years old, is tending to the sheep, which has elicited the first baa followed by a quick meh. Listening to them speak German while the birds continue their song lends the perfect soundtrack, driving home the fact that we are on vacation somewhere different than anywhere near home in Arizona.

It’s 8:30 and I run out of things to write about. Writing has been getting increasingly difficult as the trip has entered its third week. Our days have been long, averaging about 17 hours of waking activity, and by now, I’m starting to saturate with impressions. Yet, in a few days, I will start looking forward to reflecting on this amazing journey. The proverbial vacation from the vacation is in sight here during our last week in Europe.

The impressions of our perfect night in Hörsching will hopefully stay with us for the rest of our lives, and when need be, we can return to these blog entries and refresh the experience by bringing forward some of the memories that inevitably fade with time.

Does wheat in the field just look like another field of crops to a person living in the Great Plains? To me, it is exotic, full of history, essential, and beautiful in the way it moves with the wind. It deserves glamour shots as much as any of the churches we visit.

Over Hill and Dale, there is nearly always another village in the distance, and while this makes for amazing sights to those who don’t see this every day, by the time we are back in Arizona, I can fully appreciate the fact that we can drive for hundreds of miles and rarely encounter civilization aside from the needed gas station or little cafe for something to eat.

Here’s one of those random villages along the road; this one is known as Eferding, Austria.

At Cafe Konditorei Weltzer, Caroline takes time to write a couple of postcards as we share a bowl of yogurt with granola and fresh fruit accompanied by a hot pot of coffee.

It’s not a yarn store, but it’s on the same pedestal of must-visitness by Caroline. We are well off the beaten path at the Textile Center and Weaving Museum in Haslach an der Mühl, Austria. The area around Haslach, also known as the Mühlviertel, is known for its linen textile production. The Textile Center hosts an annual conference in Haslach, and there is also a biannual “Weavers’ Market.” Both of these events occur in July, but Caroline thought a visit to Haslach would be her only chance to see a weaving-centric museum in Europe and couldn’t pass the opportunity.

Once we found our way in, we wasted no time and jumped right into the main room with an incredible display of the tools used across time in the making of cloth and yarn. Above in the first part of the box is flax, which, with treatment, will become linen and one of the more sought-after fabrics available, right up there with silk and fine woolen products. Other similar boxes contained cotton, wool, man-made fibers, and yarns. These displays allowed visitors to touch the different fiber sources and the stages they passed through on the way to becoming yarn and textiles.

Flax requires three months of growth before it can be harvested, and while we do this with machines today, those machines are not able to harvest the root with the rest of the plant. For flax to produce the longest (bast type) fibers, the root should be intact during processing. After the plant is harvested, it must go through a “rippling” or “threshing” process where the seeds are removed. This is one such device that has been used for this purpose in the past.

Following this, the flax fibers must be “retted” (the word is related to “rotted,” and the result would smell about the same), which is the process of wetting the fibers and letting them age to allow the cellular structure known as “phloem” and pectin to break down. Water retting (submerging bundles of flax in-stream) takes about five days, while dew retting (spreading the flax out on the ground and spraying water on it repeatedly) can take up to six weeks. Once this action is complete, you must dry the flax before the next step, and this, too, can take a number of weeks.

Once dry, the stalks are ready to be broken. When breaking the woody outer shell, small pieces will fall away, leaving the inner fiber strand; this is the flax that will ultimately become yarn.

There were many methods used over time to break away the woody core, also known as “boon.” This can also be done by hand, but it’s a long and cumbersome process.

Before taking the fibers to the spinning wheel or spinners the various flax fibers are drawn through “hackles” to make finer filaments of flax to make more refined fabrics.

The process of drawing fibers over hackles or combs would be done several times over finer and tighter-packed spikes in order to achieve the thinnest filaments possible. The smaller the diameter of the fiber, the greater the quality of linen cloth that will be produced by this attention to detail.

In the spinning process, individual fibers are twisted and sometimes plied to make yarn. That is the intermediate step for the flax fibers before becoming linen fabric.

Once the long fibers are spun and have taken on the familiar form of yarn, it is time to bring them to the loom, where they will be woven into cloth.

These are “reeds,” which are effectively combs that keep “warp” or vertical threads separated and untangled during weaving. They are also part of the “beater bar,” which pushes the “weft” or horizontal threads into a compact structure that is the basis of the cloth we are making.

The “shuttle” holds our “weft” yarn, and when thrown through the “shed,” it adds the next row of fiber. When that is done thousands of times, we will end up with linen fabric.

Looms come in various sizes, and the type of fabric one is making will dictate what kind of loom should be used. How many “heddles” or eyelets can be manipulated by “shafts” connected to “treadles” that, when moved in particular ways, produce patterns as desired within the fabric.

While the previous loom was likely used for ribbons, decorations, and belts, this loom is better suited to towels, sheets, and yardage for cloth making.

As patterns were getting more complex the demand to automate the weaving process was becoming more important. Back in 1805, Joseph Marie Jacquard invented the Jacquard loom seen here on the left; little did he know that the design was going to inspire Charles Babbage in 1837 to propose a general-purpose mechanical analytical machine to automate mathematical computation. These developments are the basis for modern computing. One of the looms to the right of the Jacquard loom is a Broeselmaschine, which is a kind of dobby loom but over a hundred years older than Jaquard’s punch cards. It uses a belt made of wooden sticks or pegs that have bumps that trigger the lifting of shafts. There isn’t a lot of information about this type of loom online; it appears to be specific to this area of Upper Austria. Here is a link to a paper in English about digital weaving that mentions it.

Caroline is getting her first up-close examination of an earlier mechanical loom.

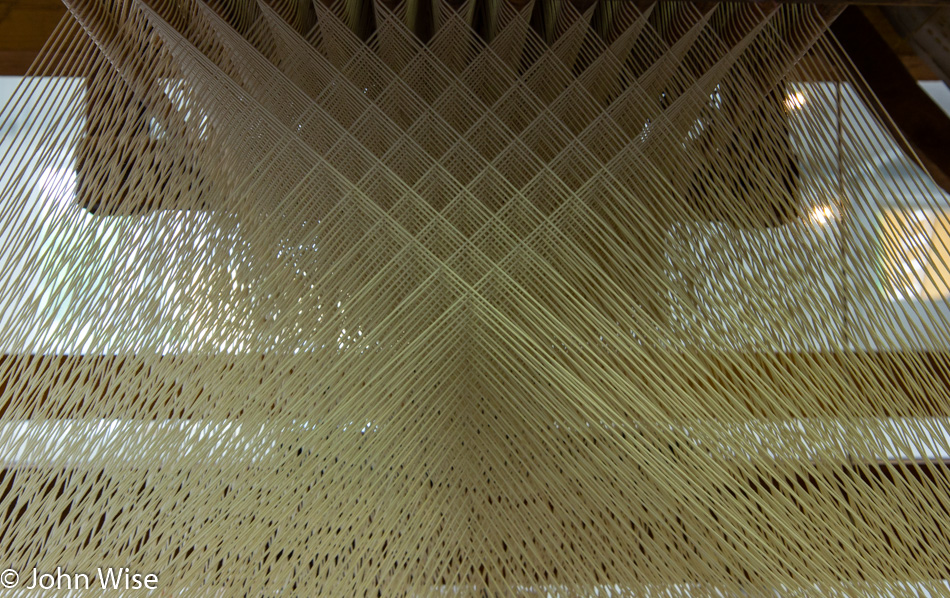

The pattern made by the warp set up in a Jacquard loom is intriguing and complex. Setting this up for the first time must be seriously time-consuming.

Stacks of punch cards ready to be fed through the Jacquard loom, creating complex patterns that would otherwise be incredibly time-consuming, are seen here.

All of the information I shared above and far more is on display right here on the main floor of the Haslach an der Mühl Textile Center and Weaving Museum.

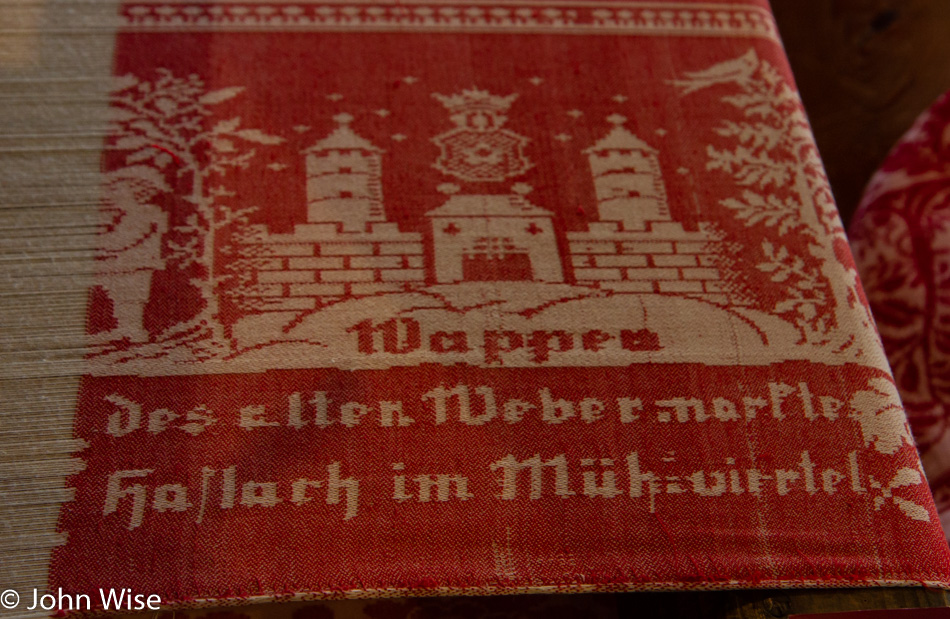

This motif says, “Crest of the old weaver’s market Haslach im Muehlviertel.” One room in the museum is called the Schatzkammer, or treasure chamber. It contains many samples of woven items made in the area.

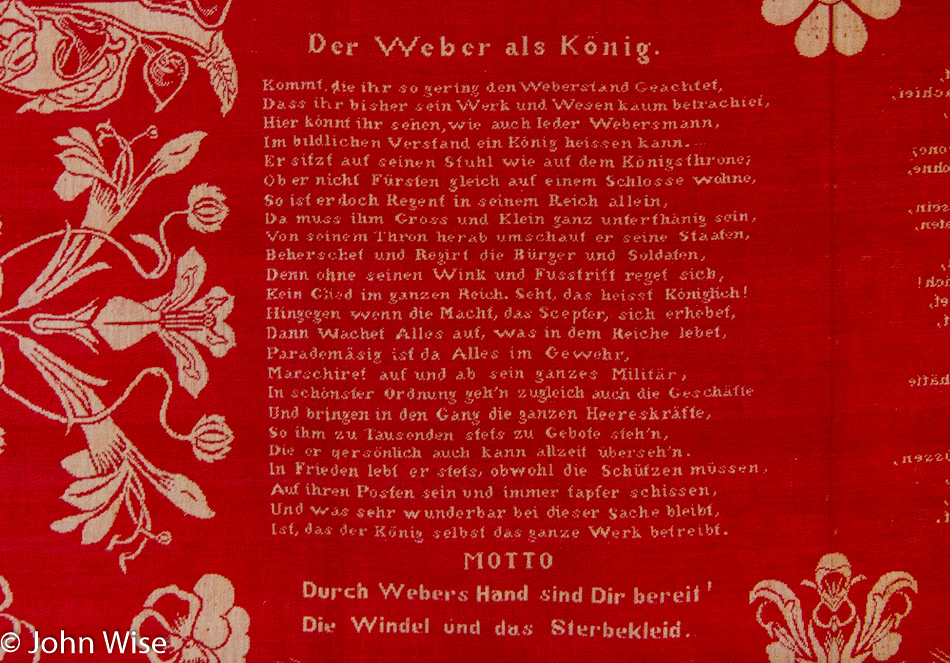

The Weaver as King

Come ye, who so poorly regard the weavers

that so far, you have barely looked at their work and beings.

Here, you can see how every weaver

can be considered a king.

He sits at his loom as on a king’s throne;

although he does not live in a palace like a prince,

he is the only ruler in his realm.

There, great and small, defer to him.

Down from his throne, he looks at his estates,

rules, and governs his citizens and soldiers.

Because without his hands and treadlings,

nothing at all will move in his kingdom. See, that is royal!

However, when the power, the scepter, rises,

then everything alive in the realm awakens.

As in a parade with rifles

his military marches to and fro.

In beautiful order, his business dealings are done

and set his armies in motion,

which are at his beck and call by the thousand,

whom he can oversee at any time.

He always lives in peace, although his shooters have to

be always on their post and courageous.

And what is even more marvelous about this is

that the king does all the work himself.

Motto: By Weaver’s hands, you are provided with diaper and shroud.

An early mechanized weaving machine from 1880 is still in operation. The gentleman who showed us this loom at work (it is LOUD!) demonstrated a few other looms for us, too. This entire experience has been well worth our deviation from our plans and in any case, the salt mine will always be there, as where who knows if funding will keep such a treasure as this open in the years to come?

Just as we were finishing up in the museum, one of the ladies who works at the museum asked if we’d like a tour of the upstairs workshop area; of course, we wholeheartedly said yes. More than a dozen looms of all sorts and sizes are available. Adjacent to the looms are half a dozen or more computers for working out patterns prior to setting up the looms when workshops are underway. Other than during special events I can’t say I know of such a well-endowed permanent space in all of the United States that is working to keep alive such an important craft as weaving.

This is why Haslach an der Mühl is known as such, as it is on the Mühl river. Flowing water is what often drove the machinery of mills and was needed for retting flax, so Haslach proved to be a perfect location for establishing a weaving center.

You never really know how many beetle species live in your environment until you try to identify a particular species. After scanning images of more than 300 varieties native to Germany and Austria, I’m no closer to knowing just which beetle family this girl belongs to. I’m guessing girl, as it doesn’t have horns. I’ll bet a dollar that Caroline, upon editing this, will have the answer, and there will be a note right here telling you what it is. – Indeed! This is a may bug, also known as a cockchafer (Melolontha melolontha). I had never seen one, even though they are memorialized in a popular German children’s rhyme. The beetles emerge from the ground in spring, lay lots of eggs in the ground, and die. Their offspring live underground for four years until they metamorphose into the final beetle stage, crawl up to mate, and start another generation of bugs.

We’ve been vigilant up to now, demanding and getting Old Country meals, often the more old-fashioned traditional cooking of days gone by at that. This afternoon though, we are making an exception and visiting a McDonalds. With our trip to the Golden Arches, we were also hoping there were some regional specialties, but alas, it was the standard fare. Although I should point out that their McCafe was extraordinary with choices we’d never see in America. Five years after my last visit to Europe we are yet to see this type of ordering in the States.

Proof that we didn’t just visit for the photo op and another chance for me to bitch about some of the backward practices and services still found in my country of birth. Look at the table behind Caroline, and you’ll see a real coffee cup and water glass.

We had to turn around for this one but who wouldn’t want to capture a couple of rotten eggs in Rottenegg?

Picked fresh roadside strawberries are certainly the taste of summer and a welcome treat.

We are in the realm of heaven or maybe the kingdom of heaven; it depends on how you want to translate the German word “Reich?” While I looked up places to stay in Salzburg, I came up with a nice farmhouse in the suburb of Himmelreich just next to Salzburg airport.

While the view is spectacular and the vacation just as much so, when I was getting our bags out of the car, I used my right knee as a deflection device for a suitcase that hit it in just such a way that the pain I started suffering was worse than when I fell on it. As I limped away from our lodging for the night to walk over to Hotel Laschenskyhof for dinner, which was just a mile away (1.7 km), I started having second thoughts about walking. The problem was that I had parked about 2 inches away from a wall because I was asked to leave as much room as possible so that a contractor showing up early in the morning would be able to pull a truck in, and our rental was a manual transmission that Caroline hasn’t driven in over 20 years. Slowly, we made it over and enjoyed our dinner, and by the time we were ready to walk back, the pain had started to subside.

The horses on the property we were staying at were friendly and curious, as were the donkeys.

Sunset over the Alps as seen from the Kingdom of Heaven. We called it an early night and skipped out on driving into Salzburg proper. We are either getting old, growing tired, or suffering from wounds that are slowing us down, but whatever this is, it better be temporary.