Go out early and beat the crowds, and you’ll have the park to yourself. There are moments one can nearly imagine what it might have been like to simply find yourself here on some random day 200 years ago before anyone would have had reason to be here. What did it mean to a tribal member of the Nez Perce to walk over the steaming earth (they are one group of several indigenous peoples we know that used to live in the area) and ponder to him or herself as to the meaning of the eternal smoke and boiling waters that were ever-present here? Why here and not north, south, east, or west of this corner of their world? How do our minds and imagination process these views when unencumbered with limits on time due to vacations coming to an end, accumulating lodging costs, or encounters with people carrying on loudly or busying themselves with electronic gear? What must it be like to set up camp in the middle of this basin and sit here for days to watch for change and never have another soul pass through?

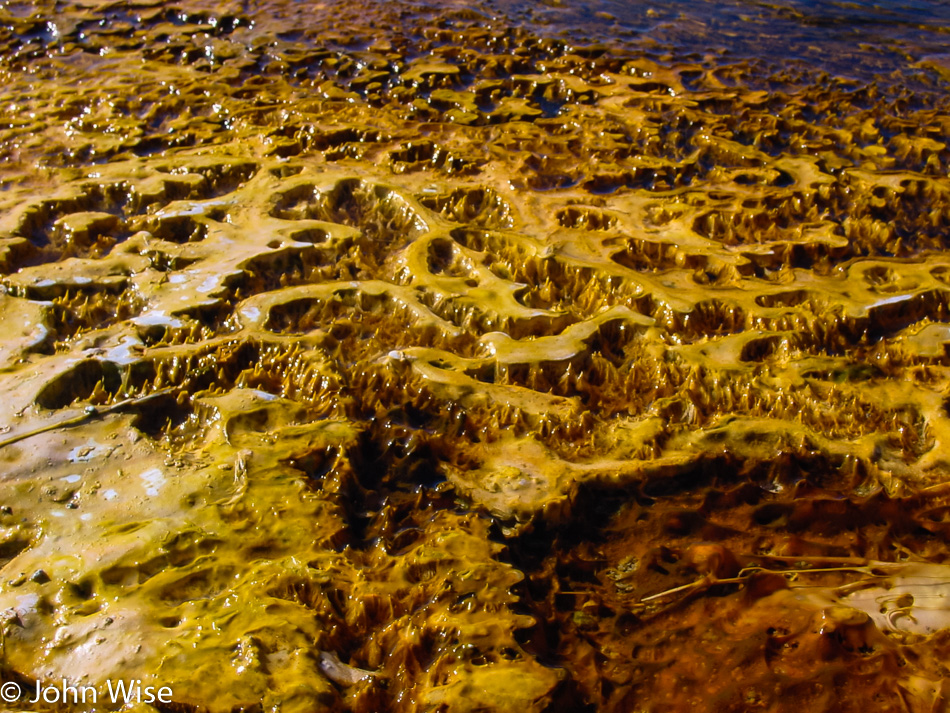

This is a thermophilic community made up of heat-loving bacteria. These bacteria form strings or filaments as water brings various other bacteria, chemicals, and minerals flowing by while the nearly ever-present cyanobacteria, through photosynthesis, release oxygen that floats to the surface, thus pushing other microbes up and creating stuff that looks like mesas and forests of spikes or, in my imagination, space chicken. The colors are, in part, determined by water temperature, though environmental factors play a role, too. Sadly, if you come to Yellowstone and you don’t already possess this knowledge or have time to talk to rangers or attend ranger programs, you could pass right through and never really know or understand a fraction of what’s occurring in this national park.

Bison have a special but contentious relationship here in Wyoming. While we visitors to Yellowstone may treasure our sighting of a herd or even a single bison, the local cattle ranchers outside the borders of the National Park believe this animal is the scourge of their operation. Bison can carry a bacterium called Brucella abortus that causes brucellosis in cattle. Infected animals suffer from lower reproductive ability, which is not good if you are a cattle rancher. The sad thing is that it was cattle a hundred years ago that brought brucellosis to the wildlife here in Wyoming in the first place, and after having become nearly extinct by the late 1880s, it is here in Yellowstone that bison have been able to start to recover. Remember that the bison population was reduced from about 60 million animals across the Great Plains in 1840 to less than 100 just 40 years later.

There’s much to learn in a national park, especially in a park that has such a rich ecosystem of biological, chemical, hydrological, and various other earth sciences that are actively at work and changing the environment rapidly. While the Grand Canyon is an amazing work of geological processes with a vast multi-billion-year history spelled out in its exposed rock layers, it isn’t changing very quickly these days; as a matter of fact, its speed of change is quite glacial. While the steam slowly rises from the hot springs here, the casual visitor might be lulled into the relaxing rhythm of the bubbling waters that seem to maintain a cadence that has always been here. The truth is that this caldera is anything but stable and is prone to rapid change, which is why it is of such interest to scientists of all disciplines from around the globe. That I should be a casual observer only taking in the superficial appearance of things feels nearly criminal. When we leave Yellowstone, all visitors should be tested for what they learned while being allowed the privilege of being present in a place of such magnitude.

Everywhere we go, and everywhere we look, there is more to greet the eye than the mind can process and so we focus on the billowing clouds of steam or the sky reflecting in the water. Then we see the brown reflective surface and the ripples of the bacterial mats in contrast to the trees on the horizon, and a larger, almost simple picture is painted. For the astute, you may recognize that this is the Midway Geyser Basin, home of the Grand Prismatic Spring.

Around the corner, a turquoise pool wants to trick us into testing the waters as shades of emerald hint at the incredible experience that could be found if only we gave into leaving the boardwalk to tread on the fragile crust of land that stands between us and what must certainly be a perfect delight. The problem arises when the reality sets in that most of the water in this area is a toasty 160 degrees (70 c) compared to a hot tub that is typically no hotter than 102 degrees (39 c) or a kitchen faucet that is set to 120 degrees (49 c). In these waters, a human will suffer third-degree burns in less than a second, and how, while you are flailing about and burning up, are you supposed to climb out of a pool with nothing to grab hold of? Heed the signs that warn visitors to stay on the boardwalks.

By now, you might be noticing that I’m not posting a lot of photos of stuff that has been posted on the internet thousands of times before. There’s so much more to this park than famous waterfalls, Old Faithful, the Grand Prismatic Spring, and bears.

This alien environment of impossible shapes, forms, and colors with exotic smells, sounds, and movement in all directions seduces my senses to the point I feel a kind of drunkenness of elation and profound disorientation that it is me, this normal nobody from Podunk, America, who can be here attempting to absorb the immensity of just what this is. To say I’m overwhelmed is the proverbial understatement. In just this photo we see moving water, possibly gas emerging from below, bacterial growth, algae, steam, and reflected light, while unseen are the rest of the microbes and geological processes that are just below the surface and invisible to our naked eye.

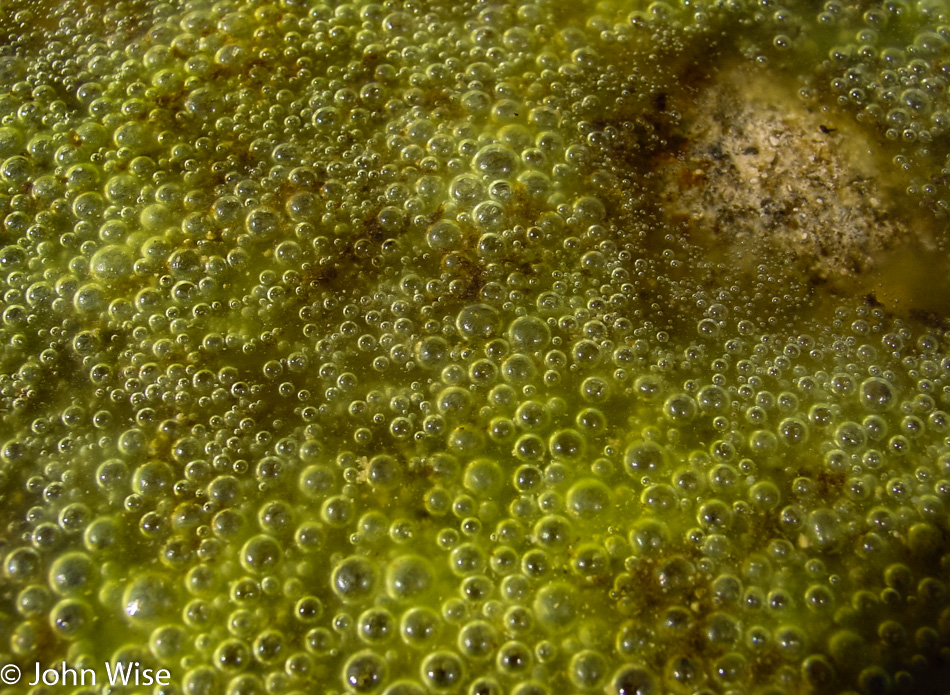

There is a serious amount of work being performed in this soup of cyanobacteria, aka blue-green algae. Just look at all that oxygen they are delivering to us!

And then there was this and I can attest to the fact that she does indeed have a seriously soft shoulder.

As far as the elk’s shoulder softness is concerned, I can’t offer any empirical data or even observational data as you’d have to be mad to approach one of these 500-pound (225 kg) animals that could put a serious hurt on you.

As the day rolls on, we have no want for better conditions. Life is perfect.

An aggressive boiling cauldron of turbid water howls in a ferocity that lets man and beast know to avoid this snarl of nature.

Meandering down the western shore of Yellowstone Lake in the direction of West Thumb, the unfolding view continues to inspire and set us in awe. Can we be this lucky?

No herds of bison today, only a couple of loners hanging out.

A porcupine scurrying about wasn’t moving so fast that we couldn’t take a few photos of this guy or girl. We’d briefly seen another porcupine down in the Tetons, but it had quickly disappeared into a storm drain. From that sighting, Caroline was able to pick up a few quills while there were none to be found from this encounter. Twenty minutes after seeing this porcupine, we spotted another grizzly bear walking through some grasses with its back to us, but a dark brown clump in tall tan grasses didn’t make for a very interesting photo.

We are about to turn back up towards Old Faithful Inn for a second night at the lodge as we are finally approaching West Thumb. On our way, we notice a strange glow low on the northern horizon (this photo is looking east prior to what I’m describing), and while it’s a bit peculiar, we figure it’s just some city north of the park, and we’re seeing city lights. The next morning, while exploring the Old Faithful Basin someone asks if we’d seen the Northern Lights last night. We had to admit that we had not, but we’d seen this strange glow; he informed us that was a clue they were going to happen. Drats, because none of us have ever seen the Northern Lights with our own eyes. Maybe tomorrow night.